Telephone Register and Lock-Out Device (Charles V. Richey, No. 1,063,599)

The patent by Charles V. Richey of Washington, D.C., describes a Telephone Register and Lock-Out Device (Patent No. 1,063,599, 1913). This invention serves a dual purpose: it acts as a mechanical meter to record completed calls (for billing purposes) and functions as a “lock-out” system to prevent unauthorized persons from using a telephone without a physical key. Crucially, it included a signaling system to notify the central office operator whether a call was successfully registered or if a station was being used in “emergency mode.”

Inventor Background: Charles V. Richey

Charles V. Richey was an African-American inventor based in Washington, D.C., during the early 20th century. His work was pivotal in the era of “party lines,” where multiple households shared a single telephone wire. Richey’s inventions focused on privacy and accountability—ensuring that users were only billed for the calls they actually made and that “eavesdropping” or unauthorized use was mechanically restricted. His mastery of electromagnetic switching and circuit signaling made him a key figure in the development of early automated telephony.

Invention and Mechanism (Simplified)

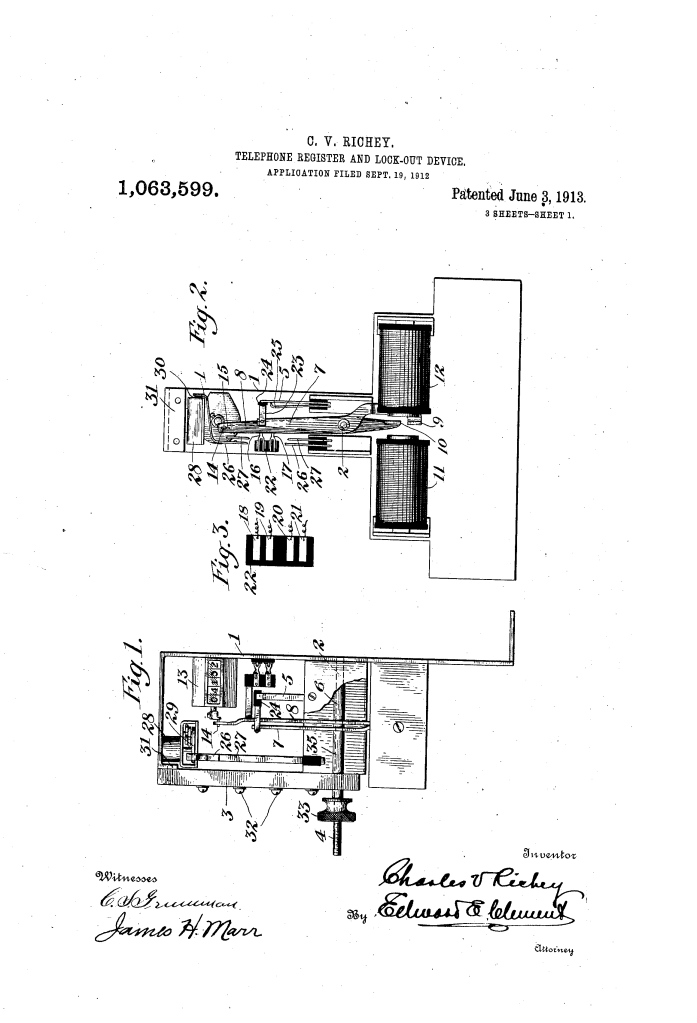

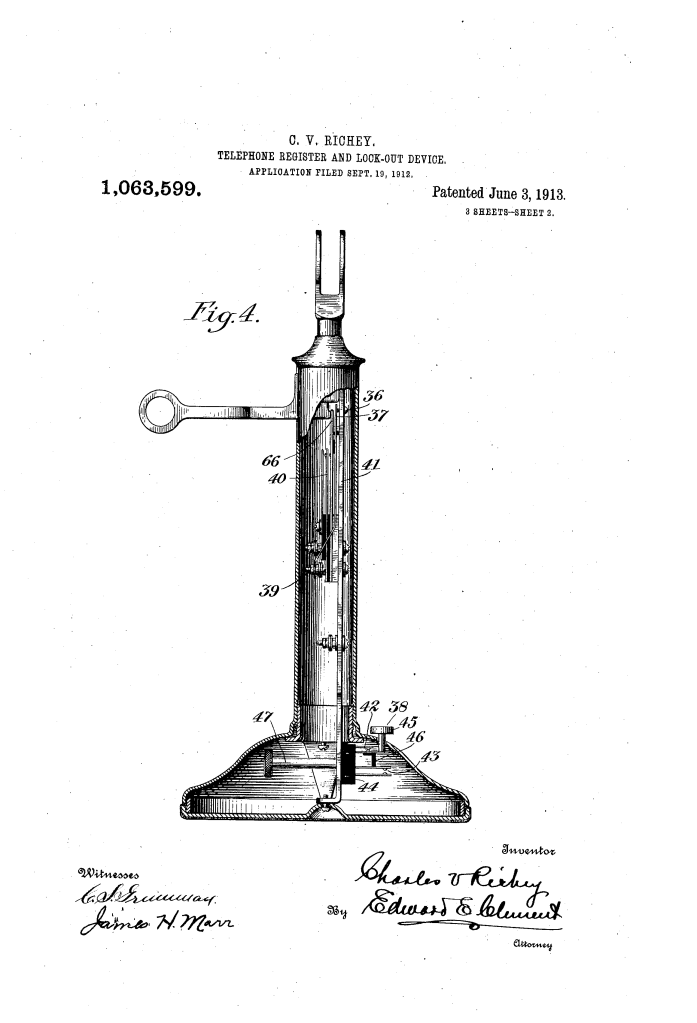

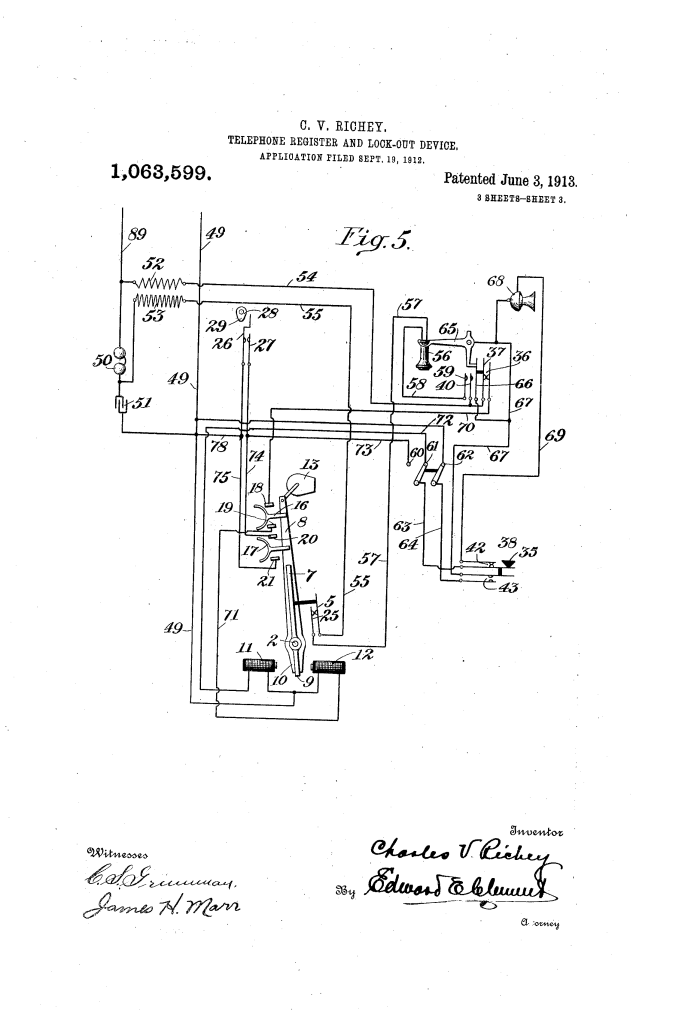

The device is an electromagnetic attachment for a standard telephone desk stand that monitors line current to trigger a meter.

1. The Call Registering Mechanism

- Magnets (11, 12) and Levers (7, 8): The heart of the device consists of two levers with armatures acted upon by magnets.

- Actuation: When the central operator completes a call, they send a ringing current over the line. This energizes magnet 11, which attracts armature 10 and swings lever 8 to the right.

- Meter (13): The movement of lever 8 is transmitted to a mechanical meter (13) via a pin-and-eye connection.

- Function: This registers one call on the subscriber’s bill. Once moved, the lever stays in the “operated” position due to the friction of a sleeve (6) on the shaft.

2. The Restoring Circuit (Fail-Safe Signaling)

- Brushes (16, 17): When lever 8 moves to register a call, it brings metal brushes into contact with electrical points (18-19).

- Restoration: When the subscriber hangs up, the switch-hook (65) closes a restoring circuit. This energizes magnet 12, which pulls the lever back to its normal position.

- Operator Notification: If the lever fails to return (meaning the call wasn’t properly logged), the restoring circuit remains closed. The operator sees a continued signal at the central office, notifying them of the mechanical failure.

3. The Lock-Out System (Unauthorized Use Prevention)

- Lock (28) and Key: The subscriber has a physical barrel lock on the phone. When locked, the transmitter circuit is broken at contacts 26-27.

- Emergency Calling: If someone without a key needs to make an emergency call, they must press a special calling key (38).

- Function: This allows them to hear the operator but not talk to her. This “silent” signal tells the operator that the phone is locked. To allow the emergency call, the operator must remotely send a ringing current to disable the lockout for that specific session.

Concepts Influenced by This Invention

Charles V. Richey’s device influenced the evolution of telecommunications billing and user authentication.

- Automatic Billing Verification: Richey’s system of “restoring signals” pioneered the logic that a machine must confirm a task (registering a call) is complete before resetting, a principle used in modern digital transaction logs.

- Remote Override Systems: The ability for an operator to “disable a lockout” via a specific frequency (ringing current) is an early mechanical version of remote administrative access used in modern software and network security.

- Anti-Buzzing Circuits: Richey included a feature where the receiver circuit (25) opens momentarily during ringing to prevent a loud buzzing sound in the user’s ear. This was an early step toward acoustic shock protection in telecommunications.

- Modular Upgrades: Richey designed the device to be installed with “minimal alteration” to existing standard Bell telephones (requiring only two holes to be drilled), reflecting an early engineering focus on aftermarket compatibility.