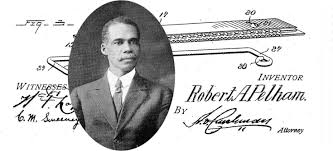

Tallying Machine (Robert A. Pelham, No. 1,079,880)

The patent by Robert A. Pelham of Washington, District of Columbia, describes a Tallying Machine (Patent No. 1,079,880, 1913). This invention is a mechanical counting and sorting device designed specifically for the heavy administrative load of the United States Census Bureau. Pelham’s primary objective was to automate the “tallying” (counting) of data from census schedules, which at the time was done by hand or with early, cumbersome Hollerith machines. His innovation provided a compact, fast, and accurate way to record statistical data while preventing the operator from accidentally skipping or double-counting entries.

Inventor Background: Robert A. Pelham

Robert A. Pelham (1859–1943) was an African American inventor, journalist, and high-ranking census official. Working in the Census Bureau, he witnessed the inefficiencies of recording massive amounts of demographic data by hand. In 1913, he was granted this patent for a machine that revolutionized the way the government processed the national census. His invention was so successful that the U.S. government used dozens of his machines, significantly reducing the cost and time required to tabulate the 1910 and 1920 censuses. Pelham is a hallmark of the Black intellectual and administrative class in D.C. during the early 20th century.

Key Mechanical Systems & Functions

The tallying machine functions like a mechanical “keyboard” for data, where each key represents a specific category (such as age, sex, or occupation).

1. The Key-Actuated Recording Mechanism

- The Keys: The machine features a series of finger-keys arranged in rows.

- The Lever Logic: Each key is connected to a transfer lever.

- Function: When a key is pressed, it actuates a specific internal counter. This replaced the “pen-and-paper” method, allowing a clerk to keep their eyes on the source document while recording data by “touch.”

2. The Locking and Reset Bar

- The Problem: Operators often accidentally hit the same key twice or failed to reset the machine between different data sets.

- The Solution: Pelham integrated a locking bar that prevented a key from being depressed a second time until the primary tally was registered.

- Function: This ensured data integrity. It forced a “one-to-one” relationship between a piece of information on a census sheet and the count in the machine.

3. The Visual Tabulator (The Counters)

- Registering Wheels: The internal mechanics consist of a series of numbered wheels (dials) similar to an odometer.

- Carrying Mechanism: Just like a modern calculator, when one wheel reaches “9,” a mechanical “carry” pawl moves the next wheel (the “tens” column) forward by one increment.

- Function: This allowed for the counting of thousands of entries across multiple categories simultaneously.

Improvements Over Manual Data Entry

| Feature | Manual Tallying (Pen & Paper) | Pelham’s Tallying Machine |

| Accuracy | High risk of human counting errors. | Mechanical precision; eliminates double-counting. |

| Speed | Slow; required looking back and forth. | Touch-system; eyes stay on the source sheet. |

| Fatigue | High mental and physical strain. | Significant reduction in clerical labor. |

| Cost | Required large teams of workers. | Automated the process, saving the government thousands. |

Significance to Data Science and Administration

Robert A. Pelham’s tallying machine influenced the development of early computing and statistical engineering.

- The Precursor to the Keyboard: The arrangement of keys for specific data entry fields anticipated the specialized keyboards and data entry pads used in modern accounting and logistics.

- Audit Trails: By using mechanical locks to prevent errors, Pelham introduced a physical form of data validation, a core concept in modern software development and database management.

- Government Efficiency: His machine was a key component in the “Modernization of the State,” proving that technology could make the democratic process of the census more transparent and faster.

- Black Professionalism in STEM: Pelham’s career as both an inventor and a senior government official served as a powerful early example of Black leadership in technical and administrative fields.