Street-Sweeper (Charles B. Brooks, No. 556,711)

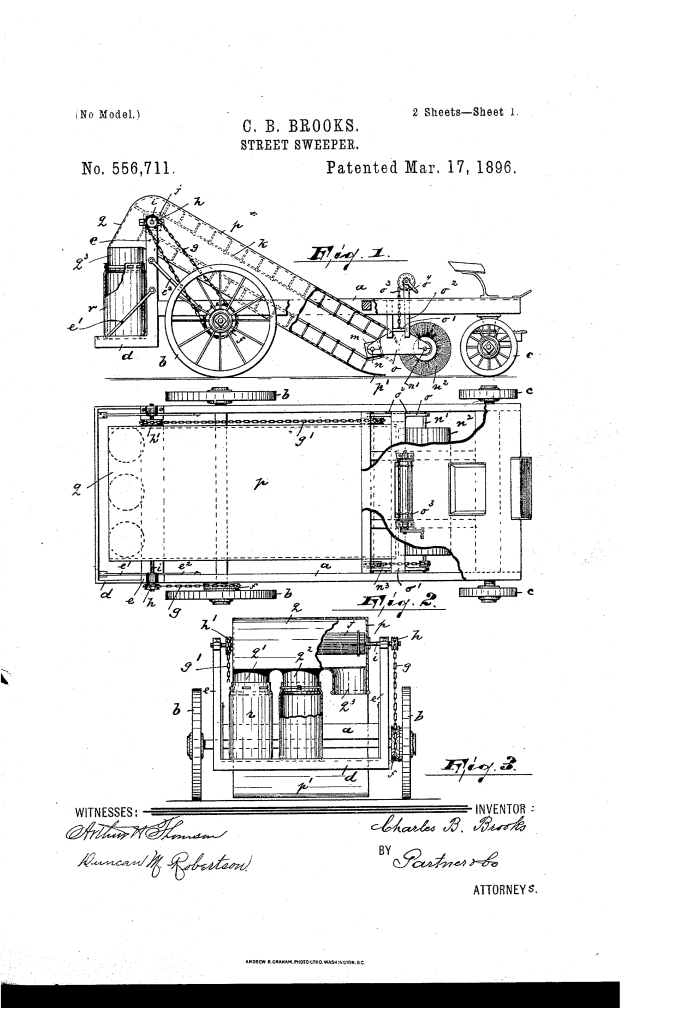

The patent by Charles B. Brooks of Newark, New Jersey, describes a Street Sweeper or Cleaner (Patent No. 556,711, 1896) designed to improve upon existing sweepers that use a revoluble brush, elevating mechanism, and refuse receptacles. The key objectives are to enhance the dust-proof nature of the machine and improve the efficiency of the elevating and sweeping mechanisms.

Invention and Mechanism

The machine is a complex, drive-wheel-powered apparatus that integrates sweeping, elevating, and debris separation.

1. Drive and Power Transmission

- Drive Wheel: One of the rear wheels (

) acts as the main drive wheel.

- Chain Drive: Power is transmitted from the drive wheel via an endless chain (

) to an upper journal (

), which carries a squared shaft (

).

- Sequential Transmission: The power continues downward through a series of chains and sprockets to a lower journal (

), and finally to the shaft (

) that mounts the revoluble brush (12).

2. Sweeping and Elevation

- Revoluble Brush (12): The brush sweeps refuse into the lower end of the elevator chute (

).

- Elevator Casing/Chute (): Inclined casing, fulcrumed (pivoted) at its upper end on the journal (

) of the upper squared shaft (

).

- Elevatory Chains (): Endless chains pass over the upper squared shaft (

) and a lower squared shaft (

). These chains carry interchangeable buckets () or scrapers.

- Refuse Handling: The lower end of the casing has a pan (

), which projects forward to catch all refuse thrown by the brush.

3. Debris Handling and Dust Control (Key Innovations)

- Squared Shaft Cleaning: The elevatory chains are designed so their links always come squarely into contact with the faces of the squared shafts ( and ).

- Function: The inventor notes that the “successive blows” delivered by these squared shafts upon the chain links are designed to free the chains of most of the dirt which clings to them, preventing refuse from falling out of the chains and creating dust.

- Dust-Proof Casing: The mouth of the elevator casing at its lower end is restricted in size and curves toward the brush, which, along with tight sealing at the top where the bags attach, is intended to make the machine dust-proof.

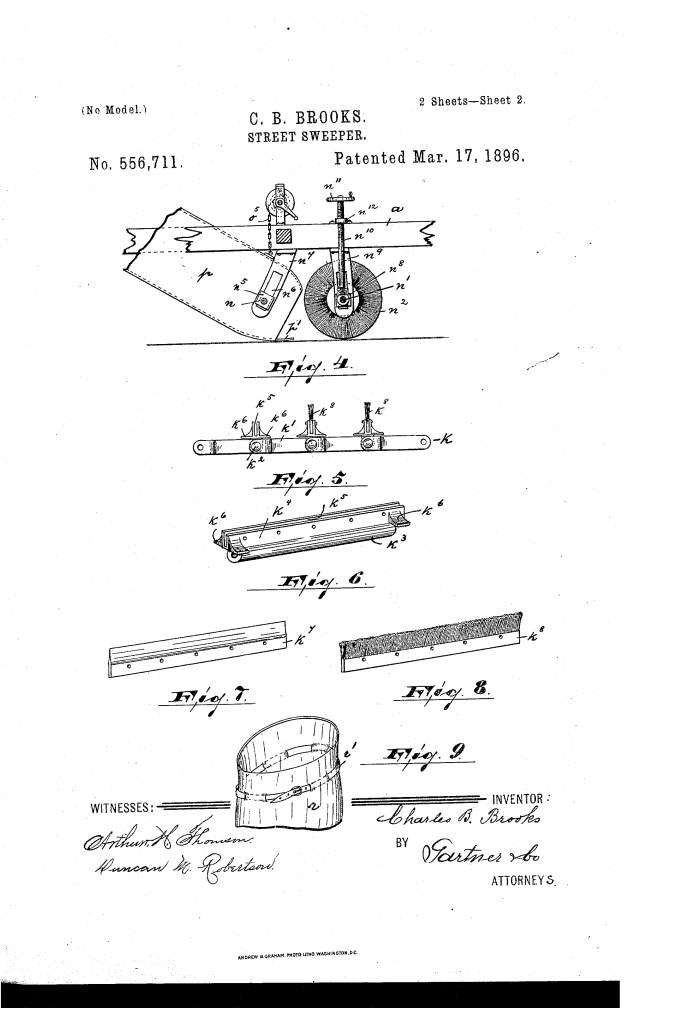

- Buckets and Spacing: The bucket-holders () are interchangeable to hold either brushes (for light work) or scrapers (for heavy work like snow, ice, or stone). They also serve to space the elevatory chains ().

- Refuse Receptacles: Refuse falls through the upper chute terminus (

) and hoppers (

) into a series of bags () carried on a rear platform. The bags are secured tightly to the hoppers by straps (

) to maintain the dust-proof seal.

4. Independent Adjustment (Modification)

- A modification is described (Fig. 4) that allows the revoluble brush () and the elevator casing () to be raised and lowered independently via separate hand-wheel-operated screws (

). This allows for flexibility in setting the brush height without affecting the elevator angle.

Historical Significance and the Inventor

Charles B. Brooks’s 1896 patent is a key innovation in the history of mechanized urban sanitation.

- Urban Sanitation Challenge: The late 19th century saw massive growth in city populations, making the task of sweeping streets (covered in everything from mud and dust to horse manure) a huge logistical problem. Early sweepers were inefficient, costly, and notoriously created large clouds of dust, negating their benefit.

- Solving the Dust Problem: Brooks’s explicit focus on making the machine “dust-proof” and the ingenious mechanical cleaning system using squared shafts were attempts to solve the biggest failing of preceding sweepers. This effort represents a significant step toward cleaner, more environmentally (and health) friendly street cleaning.

- The Inventor (Charles B. Brooks): Brooks, residing in Newark, New Jersey, was working in an industrializing urban center, placing him at the forefront of the demand for better municipal infrastructure and services.

Core Concepts Utilized Today

The sweeper’s design employs concepts crucial to modern continuous material handling and industrial machinery.

- Mechanical Self-Cleaning: The system using squared shafts () to strike and clean the elevatory chains () is an early example of a mechanical self-cleaning system. This principle is now standard in material handling for highly adhesive or sticky products, where shaker grids or mechanical knockers are built into conveyors to prevent fouling and blockages.

- Chain-Link Synchronization: Designing the chain links to align perfectly with the corners of the squared shafts for a cleaning strike is a sophisticated detail of kinematic synchronization, a feature used today in precision timing and conveying systems to manage component position relative to the drive mechanism.

- Modular Attachments (Interchangeable Buckets): The ability to use interchangeable brushes or scrapers on the elevator chains allows the machine to adapt to different loads (heavy debris vs. light dust), a key feature of modern modular industrial conveyors and bucket elevators.

- Independent Zoned Adjustment: The modification allowing independent vertical adjustment of the brush and the elevator casing is a precursor to the modern practice of zoned control in large machines, allowing separate components (e.g., the sweeper head and the vacuum nozzle) to be tuned individually for maximum efficiency over uneven terrain.