Self-Binding Harvester (W. Douglass, No. 789,010)

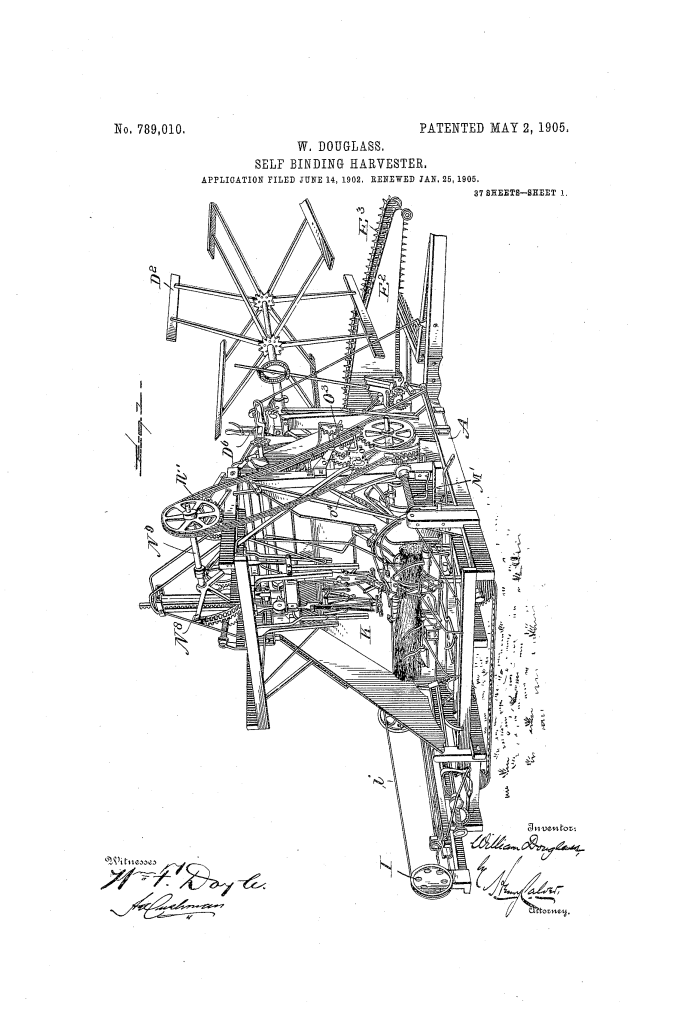

The patent by W. Douglass describes a Self-Binding Harvester (Patent No. 789,010, 1905). This is an extremely complex, large-scale agricultural machine designed to cut, gather, bundle, and bind grain in a continuous operation. The key focus is on the intricate mechanical systems required to automate the binding process reliably and adjustably.

Inventor Background: W. Douglass

While comprehensive biographical details for W. Douglass are not present in the provided patent excerpt, the nature of this invention—a massive, complex piece of machinery requiring advanced mechanical engineering—places him among the elite inventors of the early 20th century who were dedicated to mechanizing industrial agriculture. His work aimed at maximizing efficiency and production on large farms.

Invention and Mechanism (Simplified)

This harvester is an extensive system covering the entire sequence of grain processing, from cutting in the field to ejecting the finished, tied bundle.

1. Cutting and Conveyance

- Reel and Cutting Apparatus: The machine utilizes a standard forward reel to sweep standing grain toward a sickle bar (cutting apparatus)

- Platform and Conveyors: The cut grain falls onto a main platform and is moved via a series of belts and conveyors toward the central binding mechanism. The system includes intricate guides and supports to ensure the cut grain remains aligned and is fed uniformly.

2. The Knotting and Tying Mechanism (Core Innovation)

The binding mechanism is a highly complex, sequential system designed to wrap twine around a bundle and tie it securely.

- Needle: A mechanical needle is used to pass the twine around the bundle of compressed grain.

- Twine Holder and Tensioner: Mechanisms are included to hold the twine and maintain the necessary tension throughout the wrapping process.

- Knotter: A sophisticated knotting device performs the actual tying of the twine into a secure knot before the bundle is ejected.

- Timing and Control: The entire binding operation—from engaging the clutch to releasing the bundle—is driven by a precise gear and cam system synchronized to the rate at which grain accumulates.

3. Bundle Formation and Ejection

- Compressor/Packer: After the grain is cut, packing arms gather the grain and hold it temporarily in a compressor chamber to form a tight, uniform bundle before the twine is wrapped.

- Trip/Clutch Control: The machine features a trip mechanism that senses when enough grain has accumulated to form a proper bundle. This trip engages a clutch to initiate the binding cycle.

- Ejector: Once the knot is tied and cut, an ejection mechanism sweeps the finished, bound bundle off the platform.

4. Drive System

- Main Drive Wheel: The machine’s movement over the ground drives a large bull wheel (not explicitly labeled but implied by the system’s size), which powers the main drive shaft.

- Internal Gearing: The drive shaft transmits power through extensive sets of internal gears, chains, and linkages to operate the reel, cutters, conveyors, and the binder head simultaneously.

Concepts Influenced by This Invention

The Self-Binding Harvester influenced subsequent industrial automation and farming machinery by perfecting the sequential, integrated handling of materials and complex knotting mechanisms.

- Integrated Sequential Processing (Harvester): The entire machine is the ultimate example of mechanizing a long, sequential process using a single power source. This influenced the design of all subsequent combines and industrial processing lines that handle material in continuous stages.

- Automated Knotting/Tying: The refined binding mechanism, which required passing twine, maintaining tension, and forming a secure knot under heavy load, influenced the design of industrial packaging, baling, and bundling machinery that uses string, wire, or strapping.

- Accumulation Trip for Batching: The use of a mechanical trip mechanism that senses the volume of accumulated material (grain) before engaging the clutch to initiate the binding cycle influenced the design of all subsequent batching and metering systems in manufacturing and packaging.

- Cam-and-Linkage Timing: The entire binding process is a masterpiece of early 20th-century kinematics, relying on cams and multi-bar linkages to precisely time the complex movements of the needle, knife, and knotter components—a necessity for any high-speed, multi-step automated process.