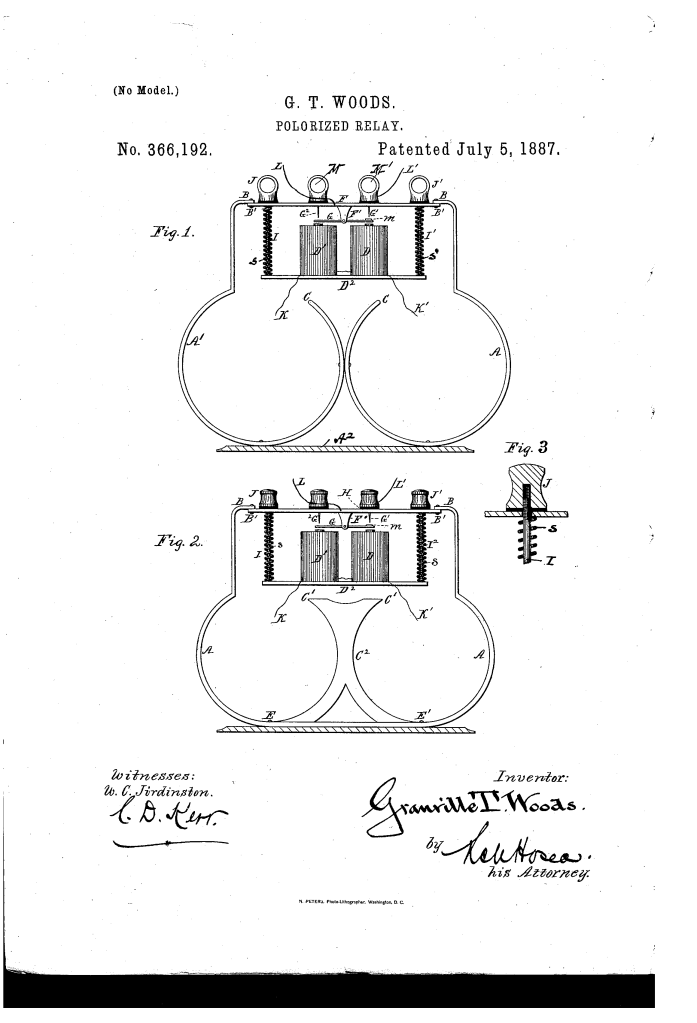

Polarized Relay (Granville T. Woods, No. 366,192)

The patent by Granville T. Woods of Cincinnati, Ohio, describes a Polarized Relay (Patent No. 366,192, 1887). This invention is an advanced telegraphic instrument designed to be more sensitive and reliable than standard relays of the era. Woods specifically engineered this device to function within his system of induction telegraphy, which allowed for communication between moving trains. A primary challenge of railroad telegraphy was that the constant jarring and vibration of the train would cause ordinary relays to “chatter” or fail; Woods’s polarized design provided a balanced, stable mechanism that remained perfectly responsive to electrical signals while resisting mechanical interference.

Inventor Background: Granville T. Woods

Granville T. Woods (1856–1910) was a legendary African American inventor often referred to as the “Black Edison.” This 1887 patent was part of a suite of inventions that revolutionized the safety of the American railroad system. By creating a relay that worked on moving cars, Woods enabled a real-time communication link between dispatchers and engineers, helping to prevent catastrophic train collisions. His designs were known for their elegant mechanical logic and high-precision adjustments.

Key Mechanical Components & Functions

The polarized relay uses a combination of permanent magnets and electro-magnets to control a delicately balanced switching arm.

1. The Permanent Magnet System (A, B, C)

- Magnets (A): Two curved permanent magnets are secured to a base.

- Bridge-Piece (F): The upper poles (B) are connected by a horizontal metal bridge.

- Function: This bridge (F) polarizes the armature (G) by induction, giving it a constant magnetic charge.

- Lower Poles (C): The lower poles of the magnets terminate beneath the electro-magnets.

2. The Suspended Electro-Magnets (D, D’)

- Adjustable Bridge (D2): The two electro-magnets (D, D’) rest on a secondary bridge (D2) that is suspended beneath the top bridge by rods (I).

- Spring Tension (s): Coiled springs surround the rods, pushing the bridge downward against adjusting-nuts (J).

- Function: By turning the nuts (J), the operator can raise or lower the electro-magnets with extreme precision. This allows the gap between the magnets and the armature to be fine-tuned for maximum sensitivity.

3. The Balanced Armature (G) (Key Innovation)

- Pivoted Design: A horizontal armature (G) is pivoted exactly in its center between the two electro-magnets.

- Mechanical Stability: Because the armature is “delicately balanced” at its center of gravity, it is naturally resistant to the up-and-down jarring of a moving train car.

- Function: The armature acts as the local-circuit controller. When reverse currents move through the main line (K), they alternately strengthen one electro-magnet while weakening the other, causing the armature to tip back and forth in perfect unison with the signal.

4. The Back-Stops and Local Circuit (G1, G2)

- Adjustable Stops: Above each end of the armature are back-stops (G1, G2).

- Electrical Path: The local circuit (L) flows through the bridge, the armature pivot, and then through the contact stop (G1).

- Action: One stop is insulated, and the other provides the contact point. This translates the faint reversals of the main line into a strong, clear signal for the local telegraph sounder.

Improvements Over Standard Relays

| Feature | Standard 1880s Relays | Woods’s Polarized Relay |

| Vibration Resistance | Heavy, lopsided arms tripped easily by train bumps. | Centrally balanced armature (G) remains neutral during jars. |

| Sensitivity | Required high-tension currents to overcome inertia. | Polarized cores and balanced poise react to low-tension induction. |

| Adjustment | Fixed components or crude screw-stops. | Micrometer-style vertical adjustment of the entire magnet bank (J). |

| Signal Quality | Prone to “sticking” or sluggish resets. | Reversing polarity actively pulls the armature in both directions. |

Significance to Electrical Engineering

Granville T. Woods’s polarized relay influenced the development of dynamic signal processing and industrial automation.

- Polarized Logic: The use of “magnetic push-pull”—where one magnet strengthens while the other weakens—is a fundamental principle in modern differential signaling and high-speed switching.

- Vibration Dampening: The mechanical poise of the armature is an early example of inertial balancing, a concept essential today for sensors used in aerospace and automotive safety.

- Precision Tuning: The vertical suspension system for the magnets (using rods, springs, and nuts) anticipated the calibrated adjustments found in modern laboratory instruments and high-end audio equipment.