Player Piano (Joseph H. Dickinson, No. 1,041,549)

The patent by Joseph H. Dickinson of Cranford, New Jersey, describes an improvement in Player Pianos (Patent No. 1,041,549, 1912). The invention focuses on an automatic control device that regulates the volume (expression) of a player piano. By using a specialized pneumatic system triggered by the perforated music sheet, the device can adjust the piano’s playing style either gradually (step-by-step) or instantly (suddenly) from soft (piano) to loud (forte).

Inventor Background: Joseph H. Dickinson

Joseph Hunter Dickinson (1863–unknown) was a prominent African-American inventor and a highly skilled organ and piano designer. He worked for many years for the Clough & Warren Organ Company and later for the Aeolian Company, where he became the head of the experimental department.1 Dickinson was a master of pneumatic logic, holding numerous patents for reed organs and player pianos.2 His work was essential in transforming the player piano from a mechanical novelty into a sophisticated musical instrument capable of nuanced, human-like expression.

Invention and Mechanism (Simplified)

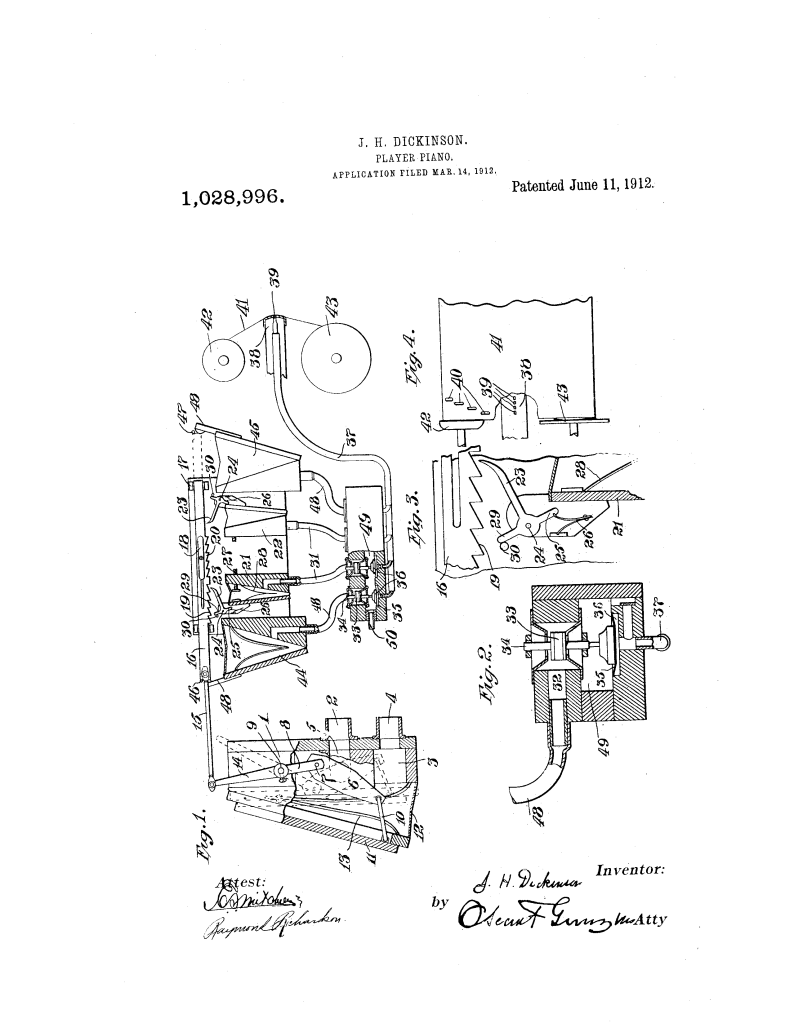

The device functions as an automatic volume controller, using air pressure (suction) to shift a valve that regulates the force of the piano’s hammers.

1. The Expression Valve (6)

- Air Regulation: A valve (6) sits over an air duct (5) connected to the piano’s “wind-chest.”

- Dynamics: When the valve is mostly closed (full lines in Fig. 1), the air pressure is low, resulting in soft playing. When it is moved to the open position (dotted lines), the pressure increases for loud playing.

- Bellows (12): A small bellows (12) and spring (13) help maintain the tension of this valve against the constant vacuum of the piano’s pump.

2. The Dual-Action Control Bar (16) (Key Innovation)

The position of the valve is controlled by a bar (16) that can be moved horizontally. Dickinson designed this bar to respond to two different types of musical requirements:

- Step-by-Step (Gradual) Change: On the edge of the bar are two racks (19, 20) with teeth facing in opposite directions. Small pneumatics (21, 22) carry pawls (23).

- Function: When the music sheet has a series of small holes, these pneumatics collapse repeatedly, causing the pawls to “kick” the bar one tooth at a time. This creates a gradual crescendo or diminuendo.

- Sudden (Instant) Change: At the ends of the bar are two larger bellows (44, 45) with long-reach arms (48).

- Function: When the music sheet has a specific large slot, these large bellows collapse instantly, pushing the bar all the way to its limit (against stops 46 or 47). This allows for a sudden change from very soft to very loud (fortissimo).

3. Tracker Bar and Music Sheet Logic

- Tracker (38) and Slots (40): The perforated music sheet (41) passes over a tracker bar (38) with four specialized ducts.

- Pneumatic Shifting: When a hole in the paper uncovers a duct, it triggers a diaphragm (35) and valve (33) that exhausts the air from the corresponding bellows, moving the bar and adjusting the piano’s volume without any manual input from the user.

Concepts Influenced by This Invention

Joseph H. Dickinson’s player piano improvements influenced the field of automated musical expression and pneumatic control systems.

- Dynamic Range Automation: The concept of having separate mechanical “paths” for gradual vs. sudden changes (the step-by-step pawl vs. the full-stroke bellows) is a fundamental principle in automated control, later seen in industrial robotics and electronic signal processing.

- Pneumatic Logic and “Programming”: By using the music sheet as a “program” to control secondary mechanical functions (volume) rather than just the primary function (striking keys), Dickinson anticipated the way modern software separates “data” from “control commands.”

- Humanized Machine Performance: His focus on “degrees of loudness” moved the player piano away from the mechanical, “honky-tonk” sound toward a more expressive, artistically viable performance, influencing the development of high-fidelity “reproducing pianos.”

- Refining Vacuum-Based Actuation: The precision of his valve and diaphragm timing helped standardize the complex air-logic networks required for early 20th-century automated machinery.