Paint and Stain and Process of Producing the Same (George W. Carver, No. 1,527,142)

The patent by George Washington Carver of Tuskegee, Alabama, describes a Paint and Stain and Process of Producing the Same (Patent No. 1,527,142, 1925). This invention details a method for transforming naturally occurring clays into high-quality wood stains, fillers, and paint pigments. Carver’s primary objective was to utilize the abundant, mineral-rich “waste” clays of the Southern United States to create durable, beautiful, and inexpensive coloring agents for infrastructure and art.

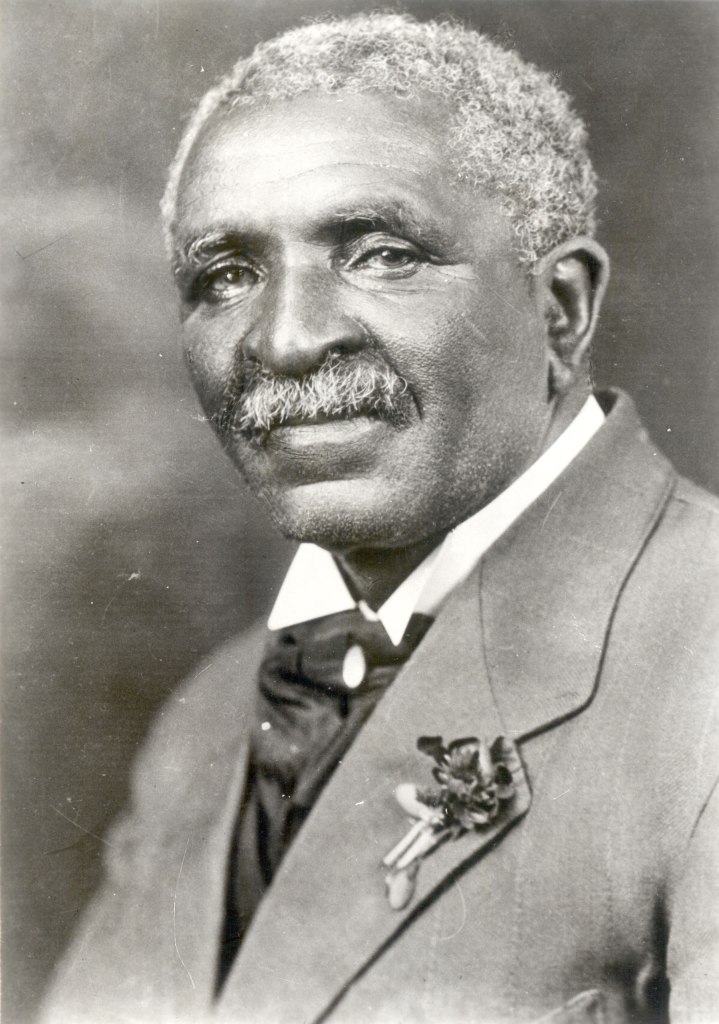

Inventor Background: George Washington Carver

While Dr. George Washington Carver is most famous for his work with peanuts and sweet potatoes, his work in mineralogy and pigment chemistry was equally revolutionary. At the Tuskegee Institute, Carver noticed that poor farmers could not afford to paint their homes to protect the wood from rot. He developed these clay-based paints so that anyone could “beautify and preserve” their property using the very soil beneath their feet. This patent reflects Carver’s commitment to “chemurgy”—the branch of applied chemistry that turns agricultural and natural resources into industrial products.

The Chemical Process

Carver’s process is essentially a method of “digesting” clay with acid to release and stabilize the iron oxides that provide color.

1. Material Selection

- The Clay: Carver specifies clay with a high iron content (ideally around 5.6% peroxide of iron and 16.7% aluminum).

- The Iron: He introduces clean scrap iron or turnings into the mix to enrich the iron content and deepen the resulting hues.

2. Acid Digestion (The “Gelatinous” State)

- The Acids: A mixture of sulphuric acid and hydrochloric acid is added to the clay and iron in an acid-proof porcelain vessel.

- The Reaction: The mixture is boiled slowly and stirred frequently. The acid dissolves the scrap iron and reacts with the minerals in the clay, turning the mass into a smooth, gelatinous paste.

3. Refining and Decanting

- Purification: The mixture is diluted with alkali-free water and allowed to settle for five minutes.

- Separation: The liquid containing the suspended fine particles is decanted (poured off), while the coarse sand and impurities that settled at the bottom are discarded. This ensures a perfectly smooth pigment.

Applications: Stains, Fillers, and Paints

Carver’s invention was versatile, serving three distinct functions depending on how the final product was handled.

| Application | Preparation Method | Performance Characteristics |

| Wood Stain | The raw gelatinous clay is applied directly to wood fiber. | It “strikes” deep into the fibers, providing a permanent color that Carver noted stayed bright for over 20 years. |

| Wood Filler | The gelatinous clay is rubbed into the grain. | It dries extremely hard, allowing the wood to take a high, glass-like polish. |

| Paint Pigment | The material is dried, ground, and mixed with linseed oil. | Acts as a high-opacity paint. Carbon or lampblack can be added to darken the shade. |

Engineering and Aesthetic Features

- Micaceous Sheen: Carver highlights that using micaceous clay (clay containing mica) from the Southern States produces a unique “sheen” or metallic luster that artificial chemical mixtures could not replicate at the time.

- Environmental Resistance: Because the pigments are derived from oxidized iron (rust’s stable cousins), they are incredibly light-fast and do not fade under harsh sunlight.

- Preservation: By acting as both a filler and a stain, the compound seals the pores of the wood, preventing moisture ingress and fungal growth.

Significance to Industrial Chemistry

Carver’s 1925 patent was a masterclass in resourcefulness. He transformed iron turnings (industrial waste) and local clay (abundant natural resource) into a high-value product.

- Democratizing Beauty: By simplifying the process so it could be done with basic equipment, he empowered rural communities to improve their living standards.

- Stability Testing: In the patent text, Carver mentions that specimens he treated 20 years prior were still “brighter and more beautiful” than when first treated, showcasing his long-term scientific rigor.

- Sustainability: Long before it was a modern buzzword, Carver was practicing sustainable engineering—reducing the reliance on expensive, imported lead-based pigments in favor of local, non-toxic minerals.