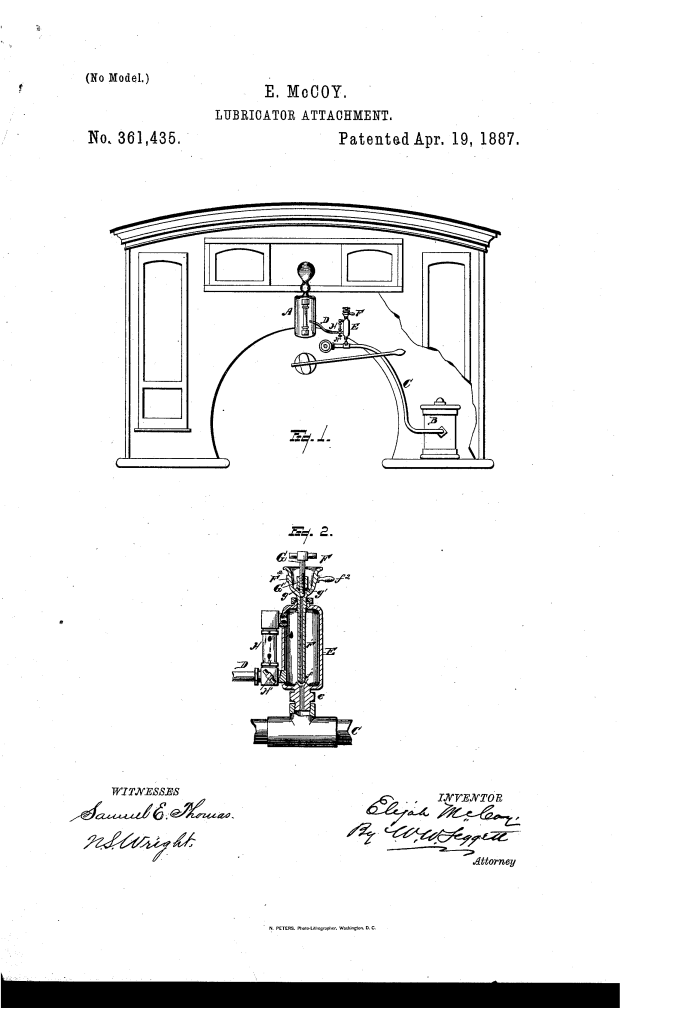

Lubricator Attachment (Elijah McCoy, No. 361,435)

The patent by Elijah McCoy of Detroit, Michigan, describes an improvement in Lubricator Attachments (Patent No. 361,435, 1887). This invention was specifically designed for use with air-brake cylinders on locomotives. It addressed a critical reliability issue in railway engineering by providing a secondary, manual method of lubrication in the event that the primary, visible-feed glass was damaged or broken.

Inventor Background: Elijah McCoy

Elijah McCoy (1844–1929) was a prolific African-American inventor and engineer whose name is famously associated with the phrase “the real McCoy.” Born in Canada to parents who had escaped slavery, McCoy trained as a mechanical engineer in Scotland. Upon returning to the U.S., he took a job as a fireman and oiler for the Michigan Central Railroad. His firsthand experience with the dangerous and inefficient practice of manually oiling moving train parts led him to invent the automatic lubricator. Throughout his career, McCoy held over 50 patents, mostly related to lubrication systems, and his work was fundamental to the safety and efficiency of the 19th-century steam engine.

Invention and Mechanism (Simplified)

Before this invention, engineers had to carry two separate types of lubricators: a “visible-feed” (which allowed them to see the oil moving) and a “blind-feed” (a backup for when the glass broke). McCoy’s attachment combined these into one system.

1. The Oil-Vaporizing Chamber (E)

- Standard Operation: Under normal conditions, oil travels from the reservoir (A) through a visible-feed glass (H) into a vaporizing chamber (E).

- Communication: The oil then passes through a hollow neck into the steam pipe (C), which carries the lubricant into the air-brake cylinder (B).

2. The Backup “Slush-Cup” System (Key Innovation)

- Hollow Valve Stem (F’): McCoy integrated a valve (F) with a hollow stem that leads directly into the steam pipe.

- Slush-Cup (F²): The top of this valve is shaped into a slush-cup (F²).

- Function: If the visible-feed glass (H) breaks, the engineer can shut off the primary oil supply and manually pour oil into this cup.

- T-Valve (G) and Orifices (g): A small T-valve (G) controls the flow from the cup into the hollow stem. McCoy added small holes (orifices g) at the base so that the engineer only needs to loosen the valve slightly to let oil flow, rather than removing it entirely.

3. Safety and Ergonomics

- Non-Conducting Handle (f²): Because these steam pipes become dangerously hot, McCoy included a handle made of a non-conducting material.

- Function: This allowed the engineer to operate the backup system with a “bare hand” even while the engine was running, without risk of severe burns.

Concepts Influenced by This Invention

McCoy’s lubricator attachment influenced the development of redundant safety systems and continuous mechanical maintenance.

- Fail-Safe Redundancy: The core concept of an integrated backup system—where a secondary manual control is housed within the primary automatic housing—became a standard safety principle in industrial engineering and aviation.

- Continuous Lubrication: McCoy’s work ensured that locomotives could operate for long distances without stopping for manual oiling, which was essential for the expansion of the transcontinental railroad and high-speed transit.

- Ergonomic Industrial Safety: By identifying the need for a non-conducting handle, McCoy pioneered “user-centered design” in the rail industry, emphasizing that safety tools must be operable under extreme environmental conditions (heat, vibration, steam).

- Standardization of the “Real McCoy”: His designs were so superior and reliable that railroad engineers specifically requested his systems by name to ensure they weren’t getting an inferior imitation, solidifying his legacy in American industrial history.