Benjamin Banneker (1731 – 1806) was born free in 1731 to a free African American mother and a former slave father who had purchased his freedom. Although he was born in a slave state and came from a lineage that included slavery, Banneker himself was never enslaved.

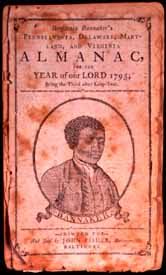

Benjamin Banneker is most renowned for publishing a series of successful Farmers’ Almanacs between 1792 and 1797. These almanacs were a remarkable achievement for a self-taught African-American astronomer and mathematician in the late 18th century, especially given the prevalent racial prejudices of the time.

Here’s a breakdown of Banneker’s Farmers’ Almanacs:

- Title and Scope: The full title often varied slightly by year and edition, but generally included “Benjamin Banneker’s Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia Almanack and Ephemeris.” This indicates the geographical reach and the astronomical focus (“Ephemeris” refers to tables giving the positions of celestial bodies at various times).

- Content: Banneker’s almanacs were comprehensive and contained a wide array of information vital to farmers and general readers of the era:

- Astronomical Data: This was the core of his work. Banneker meticulously calculated and included:

- Phases of the moon

- Times of sunrise and sunset

- Tide tables

- Astronomical information such as the true places and aspects of the planets

- Predictions of solar and lunar eclipses (his accurate prediction of a 1789 solar eclipse, contradicting others, helped solidify his reputation).

- Calendar Information: Important dates, holidays, and statistical information relevant to the year.

- Practical Advice: Information on medicines, medical treatments, and sometimes agricultural tips.

- Literary and Political Content: What made Banneker’s almanacs unique and powerful was his inclusion of essays, poems, proverbs, and significant social and political commentary. He used this platform to advocate for the abolition of slavery and racial equality.

- Letter to Thomas Jefferson: Famously, in the 1793 edition, Banneker included his powerful letter to then-Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson, challenging Jefferson on the hypocrisy of holding slaves while advocating for liberty. Jefferson’s respectful reply was also included, making this edition a significant document in the abolitionist movement.

- Other examples include “A Plan of a Peace-Office, for the United States,” and extracts from British Parliament debates on the abolition of the slave trade.

- Accuracy and Reputation: Banneker’s almanacs were known for their scientific accuracy. His calculations were praised by prominent figures like David Rittenhouse, a leading American astronomer and clockmaker. This accuracy, coupled with the fact that they were produced by a Black man at a time when African Americans were largely denied intellectual capabilities, gained him national and international acclaim.

- Publication and Distribution: Banneker initially struggled to find a publisher, but with the support of prominent abolitionists like James Pemberton and the assistance of Andrew Ellicott (whom he had assisted in surveying Washington D.C.), his almanacs were eventually published by various printers in cities like Baltimore, Philadelphia, and Wilmington, Delaware. At least 28 editions were printed across seven cities.

Significance:

Benjamin Banneker’s Farmers’ Almanacs were more than just calendars; they were a testament to his extraordinary intellect, a tool for practical guidance, and a powerful platform for social justice. They served to:

- Showcase the intellectual capabilities of African Americans.

- Disseminate crucial astronomical and agricultural information to the public.

- Contribute to the growing abolitionist movement by directly challenging racist ideologies and promoting universal equality.