Coin-Controlled Turnstile and Change Mechanism (Walter N. McClellan, No. 1,518,806)

This 1924 patent by Walter N. McClellan describes a dual-purpose transit innovation: a collapsible turnstile and an integrated automatic change-making mechanism. Designed primarily for railway cars and amusement venues, the system allows for efficient passenger flow, automated fare collection, and the ability to “fold” the turnstile flat to save space when not in use.

1. The Collapsible Turnstile Mechanism

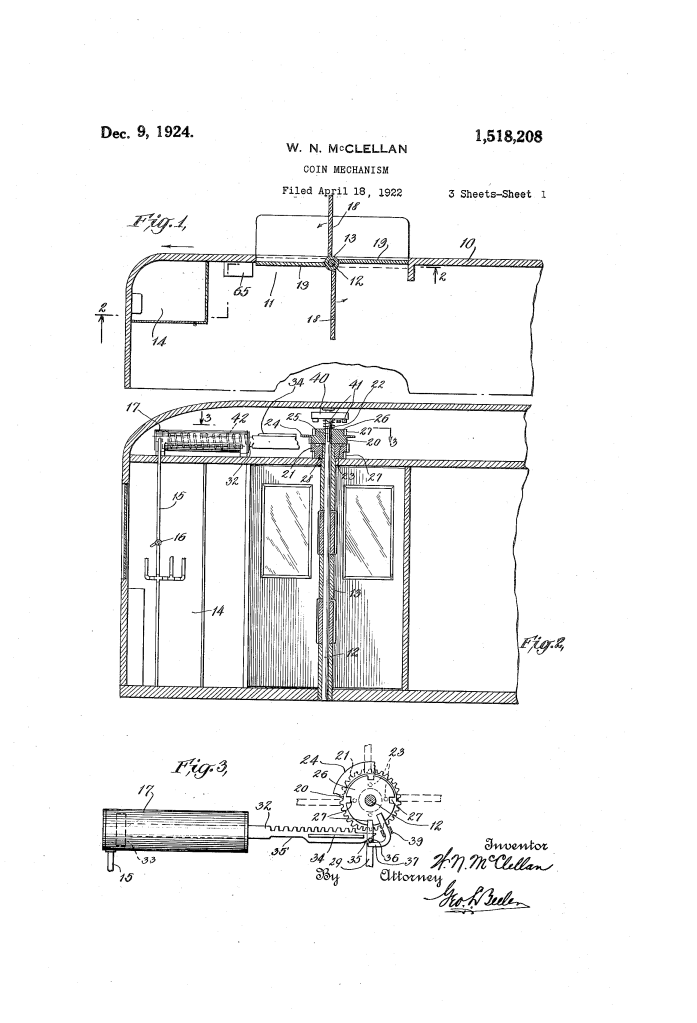

McClellan’s turnstile is engineered to be unobtrusive. When active, it functions as a standard four-wing rotating barrier. When deactivated, the wings collapse against each other to lie flush with the wall of the car.

- The Dual Shaft System: The device uses a central vertical shaft (12) and a surrounding tubular shaft (13). One pair of wings (18) is fixed to the inner shaft, while the other pair (19) is fixed to the outer sleeve.

- Pneumatic Operation: A pneumatic cylinder (17) at the top of the car uses compressed air to actuate a rack (32). This rack engages gears (20, 21) to either lock the wings into a 90-degree “X” configuration for service or fold them into a flat “II” configuration for storage.

- The Locking Bolt (29): An electromagnet (31) controls a forked bolt that prevents the turnstile from rotating until a fare is paid.

2. Automatic Fare & Change Making System

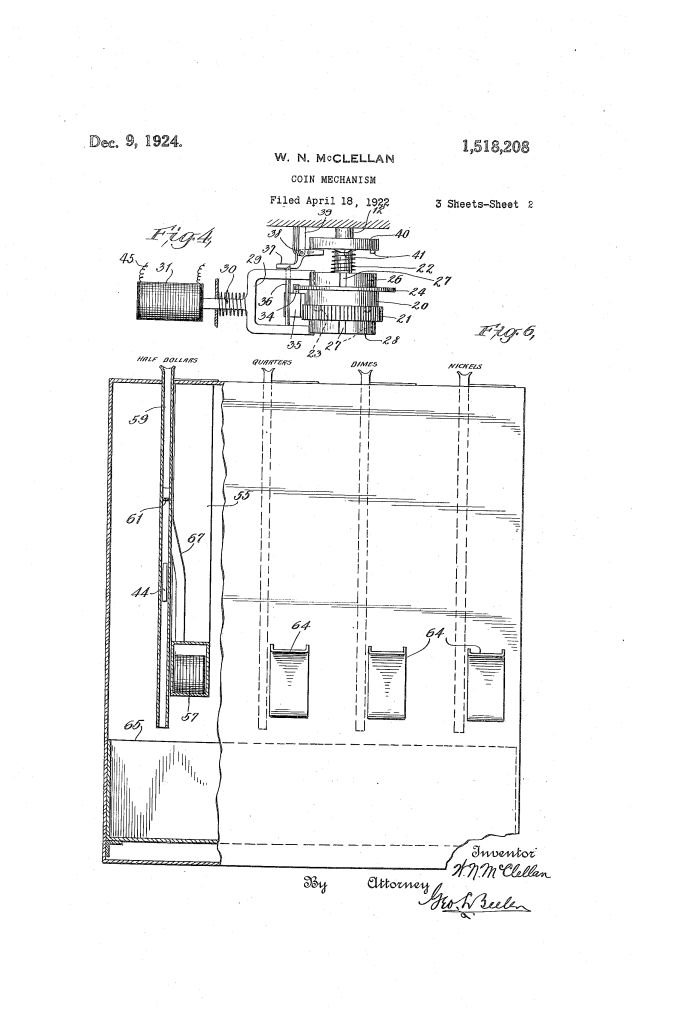

The most advanced part of the patent is the automatic change maker. Unlike standard fare boxes that required exact change, McClellan’s system could accept high-denomination coins (like a half-dollar) and automatically return the correct change (nine nickels for a five-cent fare).

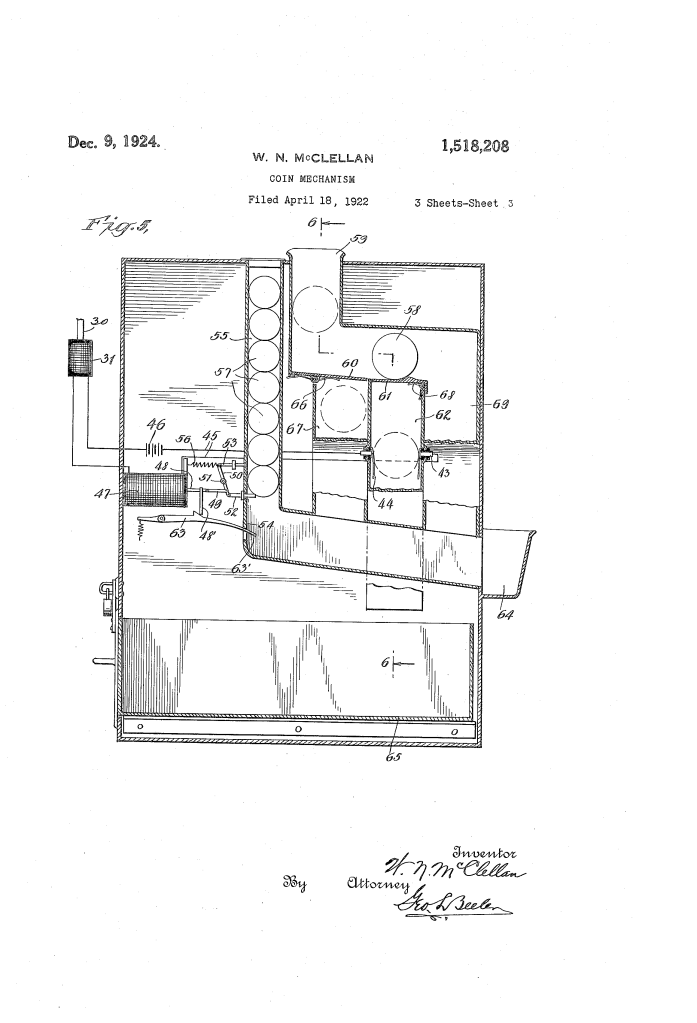

Escapement and Delivery (Fig. 5)

- Coin Magazine (55): A vertical chute holds “groups” of change (57).

- Escapement Fingers (52, 53): Two fingers operate in alternation. When the fare is paid, the lower finger (52) retracts to drop the lowermost group of change, while the upper finger (53) holds the rest of the stack in place.

- The Catch/Trigger (63): A specialized catch locks the fingers in the “release” position. The falling change coins themselves strike the trigger (63) as they exit, which physically releases the catch and allows the fingers to reset for the next customer. This ensures the mechanism doesn’t jam or reset before the change is fully delivered.

Fraud Detection and Sorting

The system includes “trap doors” to verify the authenticity of the inserted coin:

- Overweight (Bogus Slugs): A spring-supported trap door (60) is calibrated to collapse under the weight of heavy lead slugs, diverting them to a rejection chute (67).

- Underweight (Counterfeit): A second trap door (61) allows lightweight coins to roll over it without falling into the “paid” slot, returning them to the customer via chute (69).

- Circuit Bridging: A valid coin bridges two contacts (43, 44) in the auxiliary chute, completing an electrical circuit that triggers the turnstile’s unlock magnet and the change-making motor simultaneously.

Engineering Summary Table

| Feature | Engineering Solution | Function |

| Pneumatic Rack (32) | Converts air pressure to rotational force. | Collapses/extends the turnstile wings. |

| Electromagnet (31) | Solenoid-actuated armature. | Unlocks the turnstile rotation remotely upon payment. |

| Timing Catch (63) | Mechanical feedback loop. | Uses the physical weight of falling change to signal the end of a transaction. |

| Concentric Shafting | Inner shaft (12) + Outer sleeve (13). | Allows wings to move independently during the folding process. |

Historical Significance

McClellan’s invention solved a major logistics hurdle for New York’s transit systems. By integrating change-making directly into the turnstile, he removed the need for a human booth attendant to make change, effectively creating the first fully automated “self-service” subway entrance. His use of a “timing catch” based on the physical presence of the product (the coins) is a classic example of robust mechanical logic used before the era of electronic sensors.