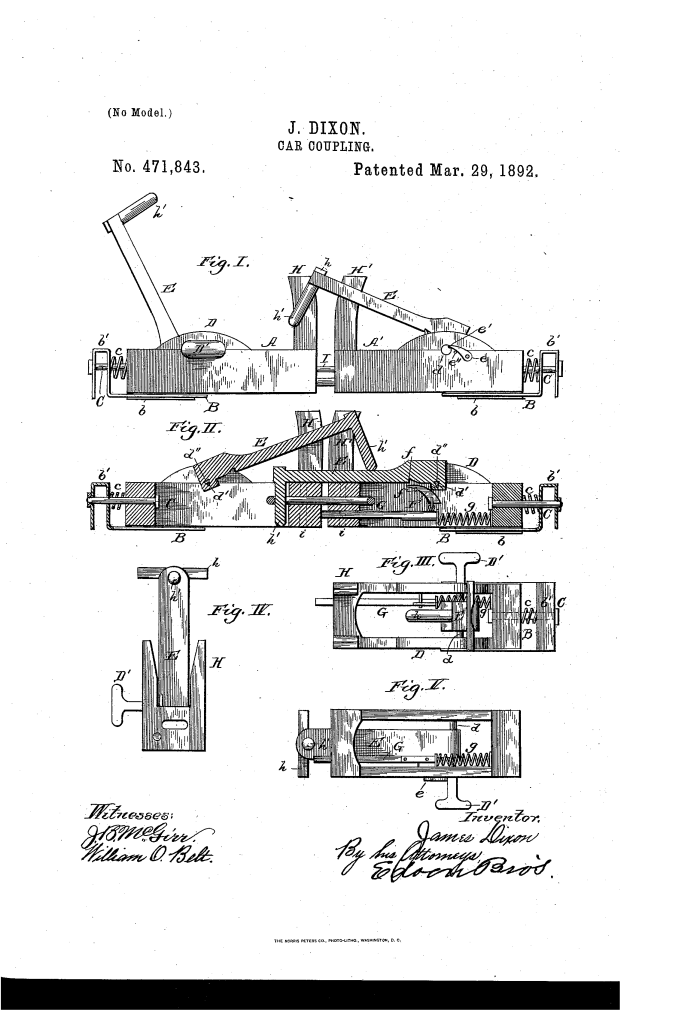

James Dixon’s patent for a Car-Coupling, No. 471,843, describes a type of automatic coupler designed to connect railway cars together without a person having to stand between them. Patented on March 29, 1892, the invention aimed to create a simple and effective coupler where each draw-head had all the necessary parts for a complete connection.

The key features of the coupling were:

- Pivoted Gravity Pin: Each draw-head had a coupling pin that was pivoted and held in an elevated position by a spring-actuated pusher-bar that extended from the front of the draw-head.

- Automatic Engagement: As two cars approached, the pusher-bar of one car would be pushed backward by the opposing draw-head. This action would pull a trigger from beneath the elevated coupling pin, allowing it to fall into a socket on the opposite draw-head and complete the coupling.

- Locking Detent: A pivoted detent was included to engage with the coupling pin’s pivot, locking it in place and preventing it from becoming uncoupled from any sudden jolts.

- Buffer Mechanism: The rear of the draw-heads had a spring cushion to ease the jarring impact of the cars when they coupled.

Societal Impact and Legacy

Dixon’s invention was part of a major wave of innovation in railway safety that revolutionized the industry and saved countless lives.

- Revolutionizing Railway Safety: Before the widespread adoption of automatic couplers, railway workers had to manually connect cars using a link and pin. This was an extremely dangerous and often fatal task, as it required them to stand between the cars as they were coupled. The Interstate Commerce Commission’s push for automatic couplers in the late 19th century made inventions like Dixon’s critically important.

- Improving Efficiency: Automatic couplers not only improved safety but also increased the speed and efficiency of railway operations. Trains could be coupled and uncoupled much faster, reducing delays and improving the flow of goods and people.

- The Inventor’s Legacy: The patent record for James Dixon does not contain information about his life beyond his residence in Cincinnati, Ohio. His invention, however, is a clear example of how inventors responded to a major public need, contributing to the development of a safer and more modern railway system.