Ellis Little’s patent for a Bridle-Bit, No. 254,666, describes a harness bit designed for quick and easy attachment and detachment of a horse’s bridle and reins. Patented on March 7, 1882, the invention aimed to eliminate the need for buckles, saving time and effort for people who worked with horses.

Key Features

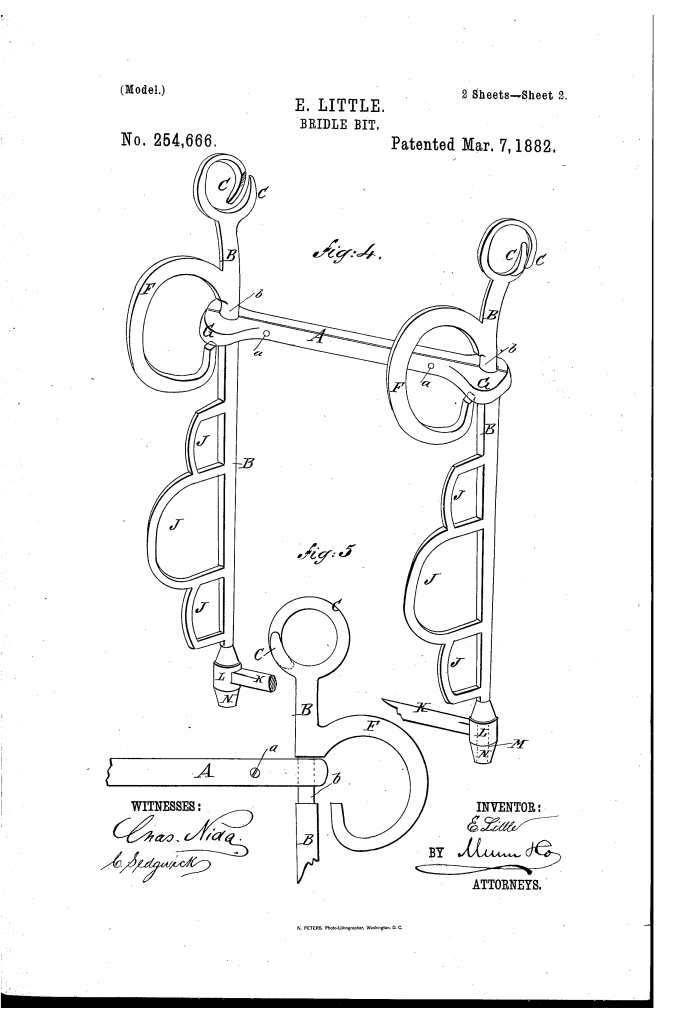

- Swinging Rein-Hooks: The bit’s side bars had curved hooks that would swing under the ends of the mouthpiece. To attach or remove a rein, a user could turn the side bar, swinging the hook out from under a projection on the mouthpiece, which would open the hook. This allowed straps to be slipped on or off without having to unbuckle them.

- Split Rings: The upper ends of the side bars featured split rings for the cheek and curb straps. These rings had a small gap that was designed to let a strap slide in sideways but would not allow it to come out during normal use.

- Two-Part Mouthpiece: The mouthpiece was made in two parts that were screwed together. This allowed the mouthpiece to be easily attached to or removed from the side bars.

- Up-and-Down Movement: The mouthpiece was designed with a slight up-and-down movement on the side bars to facilitate the insertion and removal of the straps from the curved hooks.

Societal Impact

Little’s invention was a practical improvement on a foundational piece of equipment in a world still reliant on horsepower.

- Efficiency and Convenience: By simplifying the process of attaching and detaching a bridle, the invention saved time and effort for farmers, teamsters, and anyone who worked with horses. This was a valuable innovation for a society where horsepower was essential for transportation and labor.

- A Glimpse into the Past: This patent shows how inventors focused on refining existing technologies to make them more efficient and user-friendly. It is a reminder of the kind of pragmatic ingenuity that was applied to the problems of a pre-automobile economy.

- The Inventor’s Legacy: The patent record for Ellis Little does not contain information about his life beyond his residence in New York, New York. His work, however, stands as an example of the thousands of inventors who created devices that, while not world-changing, made a direct and tangible improvement to the lives of working people.