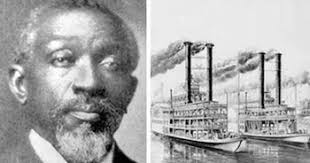

Benjamin Montgomery (c. 1819-1877) was an extraordinary African-American inventor, mechanic, and businessman, most famous for inventing a shallow-water steam propeller specifically designed to improve steamboat navigation on rivers with varying depths, like the Mississippi.

However, his story is also a poignant example of the injustices faced by enslaved inventors in the United States: he was denied a patent for his invention because he was enslaved.

Here’s what makes Benjamin Montgomery’s shallow-water steam propeller significant:

- The Problem it Solved: Steamboats were crucial for commerce and transportation on American rivers in the mid-19th century. However, many rivers, including the Mississippi, had sections that were very shallow, causing steamboats to run aground, get stuck, or force them to take long, inefficient detours. This resulted in significant delays and economic losses.

- Montgomery’s Solution: Working on the Hurricane Plantation (owned by Joseph Davis, brother of Jefferson Davis, future president of the Confederacy), where he was responsible for various mechanical and logistical operations, Montgomery designed a revolutionary propeller.

- His propeller blades were designed to enter the water at an angle, rather than directly pushing straight back. This allowed the propeller to operate more efficiently in shallower water and cut through the water with less resistance, enabling steamboats to navigate areas previously considered too shallow or dangerous.

- It’s sometimes described as operating on a “canoe paddling principle,” providing a more effective thrust in challenging conditions.

- The Patent Denial: In 1858, Joseph Davis, recognizing the immense value of Montgomery’s invention, attempted to secure a patent for it. However, the U.S. Patent Office, backed by the U.S. Attorney General’s opinion (Jeremiah Black), denied the application. The official ruling was that slaves were not considered citizens and therefore could not own property, including intellectual property like a patent. This denial was a direct consequence of the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which declared that African Americans, whether enslaved or free, could not be U.S. citizens.

- Subsequent Attempts and Recognition:

- Both Joseph and Jefferson Davis (who later became president of the Confederacy) reportedly tried to patent the propeller in their own names, but these attempts were also denied because they were not the true inventors.

- During the Civil War, Jefferson Davis, as president of the Confederacy, did try to change Confederate law to allow slave owners to patent inventions made by their slaves, but the war’s outcome prevented this from having any lasting effect.

- Although he never received a U.S. patent during his lifetime, Montgomery’s propeller was widely recognized for its effectiveness. After gaining his freedom, he continued to develop and even exhibit his propeller at major expositions, such as the 1876 World’s Fair in Philadelphia.

- Beyond the Invention: Benjamin Montgomery’s story extends far beyond this invention. After the Civil War, he purchased the Hurricane Plantation from Joseph Davis and became one of the wealthiest African-American landowners and businessmen in Mississippi. He established a thriving market center called Montgomery and Sons, which included a store, warehouses, and a steam-driven cotton gin. His son, Isaiah Montgomery, later founded the all-black town of Mound Bayou, Mississippi.

Benjamin Montgomery’s shallow-water steam propeller stands as a testament to his extraordinary ingenuity and the systemic barriers that prevented enslaved individuals from receiving the recognition and protection for their intellectual contributions.