Benjamin Boardley (born March 1830, died 1904) was an incredibly ingenious African-American inventor, notable for his work on steam engines for ships. What makes his story particularly compelling, and tragic, is that he was born enslaved, and therefore was unable to legally patent his inventions under U.S. law at the time.

Despite this barrier, his mechanical genius was widely recognized by those around him, especially at the U.S. Naval Academy where he worked.

Here’s what is known about Benjamin Boardley’s steam engine work for ships:

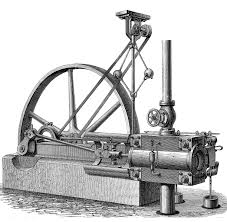

- Early Demonstrations of Genius: Boardley’s mechanical aptitude was evident from a young age. While still enslaved, around age 16, he built a working steam engine out of scraps from items like a gun barrel, pewter, and steel. This feat impressed his enslaver, John T. Hammond, who then secured him a job as a helper in the Department of Natural and Experimental Philosophy at the Naval Academy in Annapolis.

- Work at the Naval Academy: At the Academy, Boardley assisted professors in setting up experiments and continued to hone his skills. He was recognized by professors as a quick learner who sought to understand the “scientific law by which things act.” The children of Professor Hopkins at the Academy even taught him reading, writing, and mathematics (arithmetic, algebra, and geometry).

- Developing Steam Engines for Ships: While at the Naval Academy, Boardley designed and built several steam engines:

- He built a smaller steam engine, powerful enough to run a small boat, which he sold to a midshipman.

- Using the proceeds from this sale and his limited earnings (his enslaver received most of his wages), he then developed and built a more powerful steam engine.

- This larger engine was significant because it was reportedly capable of propelling the “first cutter of a sloop-of-war” (a small ship’s boat carried by larger warships) at speeds exceeding 16 knots (approximately 18 mph). This was a remarkable speed for a steam-powered vessel of that type in the mid-19th century (around 1859).

- He is also credited with selling this model engine, which then helped him finance the design and construction of an even larger engine intended for the “first steam-powered warship.”

- No Patent Due to Enslaved Status: Crucially, because Boardley was an enslaved person until 1859, he was legally prohibited from obtaining a U.S. patent for any of his inventions. This was a common and unjust reality for countless enslaved inventors in the antebellum United States.

- Purchasing His Freedom: Despite not being able to patent his work, Boardley was able to sell his innovative engines. He used the proceeds from these sales, combined with money gifted to him by sympathetic professors at the Naval Academy, to purchase his freedom for $1,000 in September 1859.

- Post-Emancipation Career: After gaining his freedom, Boardley continued his work. During the Civil War, when the Naval Academy relocated to Newport, Rhode Island, he was employed there as a free man and worked as an instructor in the Philosophical Department in 1864, continuing to construct small steam engines. Later in life, he lived in Mashpee, Massachusetts, and was listed as a merchant and a “philosophical lecturer.” In the 1880s, he worked with Herbert Crosby to build a 35-foot steam-powered boat called Quichatasett (later renamed Ruth), which was launched in 1891 and popular with fishermen and tourists.

Benjamin Boardley’s contributions to steam engine technology, particularly for maritime applications, were significant, even though his enslaved status prevented him from receiving the official recognition of a patent. His story is a powerful testament to the unyielding ingenuity of enslaved people and the profound injustices of the institution of slavery.