Table of Contents

- Introduction: Lessons from the Screen and the Father

- The Roots of the Riches: Taft and the Trail of Tears

- The Legacy of the “Missed Dirt”: A Family Lesson

- The Gusher and the “Guardian” Trap

- The “Honorary White” Maneuver

- The Battle for the Mind: The Competency Trials

- Mineral Rights: The Geometry of the “Underground”

- Modern Deterrents: The New Guardianship

- The Power of the Trust: Protecting Your Legacy

- Conclusion: The “Two Cents” Strategy

- Glossary of Terms

- Bibliography

1. Introduction: Lessons from the Screen and the Father

I recently watched a film called Sarah’s Oil. It tells the remarkable story of Sarah Rector, a young African American girl born in Oklahoma’s Native American territory in the early 1900s. Against all odds, she became one of the wealthiest African American children in the early 20th century, a millionaire at a time when most people—Black or white—were struggling to make ends meet.

Watching her story, I couldn’t help but think of my own father. He understood the fundamental importance of owning property with a clarity that bordered on the sacred. He taught my siblings and me that lesson early on and practiced it himself throughout his life. It is no accident that in the early history of America, only land-owning men were granted the right to vote. That is how much owning property is valued in this country; it was once the literal gatekeeper to citizenship and personhood. If you didn’t own a piece of the earth, the system decided you didn’t truly count.

While the film captures the triumph of a “gusher” in the Oklahoma dirt, it also opens a door to a much darker chapter of American history: the era of “White Guardianship.” This is the story of how the law was used to separate Black and Native families from their land, and why we must use every modern tool at our disposal—specifically Trusts—to ensure history does not repeat itself.

2. The Roots of the Riches: Taft and the Trail of Tears

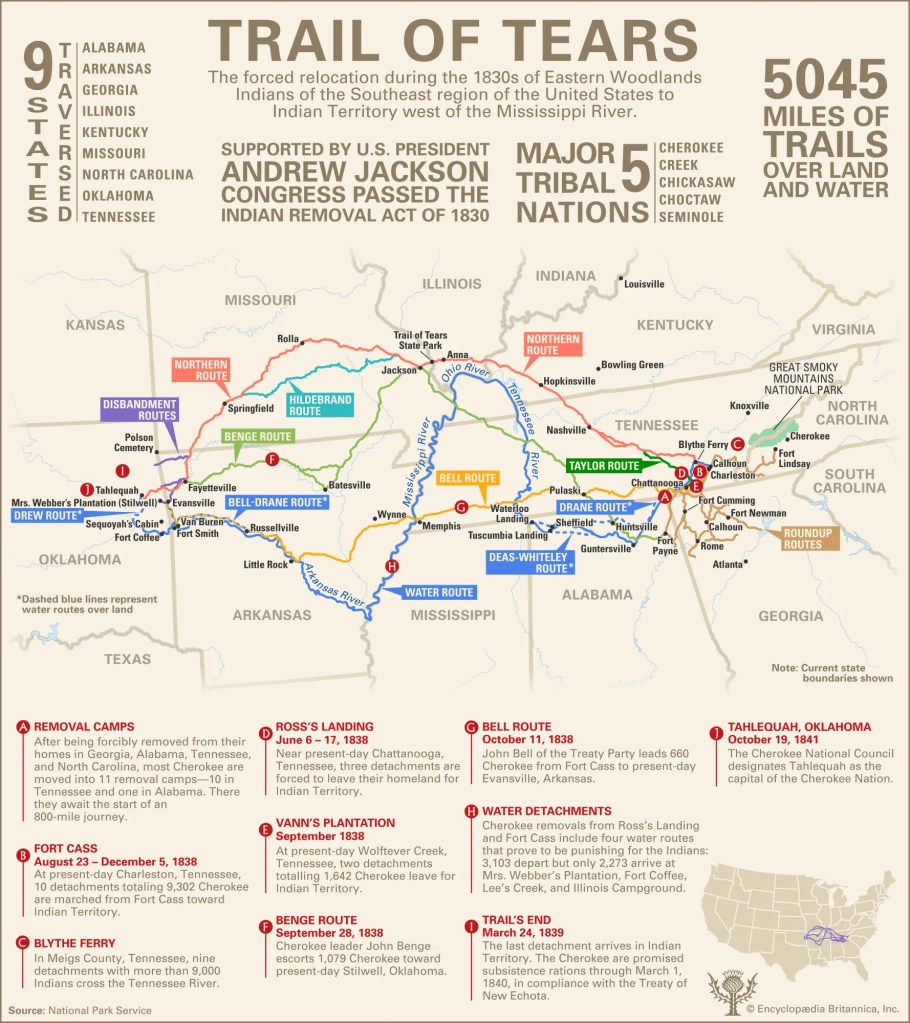

To understand Sarah Rector, you have to understand where her land came from. Sarah was a descendant of “Creek Freedmen”—African Americans who had been enslaved by the Muscogee (Creek) Nation. When the Creek people were forcibly removed from their ancestral homes during the Trail of Tears, they brought their enslaved populations with them to “Indian Territory,” now Oklahoma.

After the Civil War, treaties required the Creek Nation to grant these Freedmen citizenship and land. By the late 1890s, the Dawes Allotment Act was passed to break up communal tribal lands into individual plots. The goal was twofold: to force Native and Black populations into private ownership and to open “surplus” land to white settlers.

To the casual observer, the Dawes Allotment Act looked like a gift of private property. However, it was a calculated trap designed to dismantle the power of communal land. By forcing Native and Black populations into individual, private ownership, the government effectively broke the “strength in numbers” that tribal land provided.

Once the vast tribal territories were carved into small 160-acre “checkerboards,” the law conveniently labeled any land not assigned to an individual as “surplus.” This “surplus” land—often the most fertile and resource-rich—was then legally opened to white settlers and corporate speculators.

Furthermore, by moving from communal to private title, the land became subject to taxation and foreclosure. Many families, who were used to living off the land without the burden of property taxes, suddenly found themselves in debt to the state. This created a “legal pipeline” where Black and Native land could be seized by the court for unpaid taxes and sold to white neighbors for pennies on the dollar. Private ownership wasn’t just about giving Sarah Rector a plot of dirt; it was about isolating her wealth so it could be more easily targeted by the “guardians” and “oil sharks” waiting in the wings.

Historically, communal tribal land held in “trust” by the federal government was tax-exempt. However, the Dawes Act fundamentally changed the legal status of the land to force Native and Black populations into the American capitalist system. This was achieved through a “Trust-to-Tax” pipeline:

- The Competency Trap: Originally, allotments were meant to be held in trust (and tax-free) for 25 years. However, the Burke Act of 1906 gave the government the power to declare an individual “competent” without their consent. Once declared competent, the land was converted to “Fee Simple”—meaning it became fully taxable by the local county overnight.

- Targeting the Freedmen: Because Sarah was a “Creek Freedman,” her land was even more vulnerable. In 1908, Congress removed the “restrictions against alienation” for Freedmen land. While white settlers were often given tax breaks to develop their farms, Black and Native owners were hit with tax bills they couldn’t pay, often for land that had been intentionally selected for its poor farming quality.

- Foreclosure by Pen, Not Sword: This created a massive “tax-sale” market. If a family couldn’t pay the new taxes—often because they were barred from getting fair bank loans—the state would seize the property. Speculators would then buy a million-dollar oil-rich plot for the price of a single year’s back taxes.

By forcing Sarah into individual private ownership, the state of Oklahoma successfully turned her greatest asset into a debt. They didn’t need an army to take the land; they just needed a tax collector and a “white guardian” to manage the “problem” of her wealth.

Sarah and her family were each given 160 acres. The system was rigged: white “allotters” ensured the most fertile land went to white homesteaders. Sarah’s plot in Taft, Oklahoma, was written off as “worthless”—a rocky, infertile patch of dirt. Taft was one of over 50 “All-Black Towns” in Oklahoma, places meant to be havens of autonomy. Yet, even in a Black town, the long arm of white-controlled county courts could still reach in.

3. The Legacy of the “Missed Dirt”: A Family Lesson

The struggle Sarah faced to keep her land reminded me of a story my father told me about his own father—my grandfather. It was a story about a missed opportunity that stayed with my father his entire life, eventually shaping the way he looked at every real estate deed he ever signed.

My grandfather grew up in a house on a plot of land. At one point, the owner of that land offered my grandfather the chance to buy the entire area—acres of land that surrounded the family home. In his words, he could have bought it for “almost nothing.” It was one of those rare moments in history where a small amount of capital could have secured an enormous future for generations to come.

But for reasons lost to time—perhaps the crushing weight of the era or the simple risk of the unknown—he didn’t do it. He bought the house and the immediate yard, but he let those surrounding acres go. Today, that land isn’t an open field anymore. It has a whole community built on it, with a few dozen houses.

My grandfather could have owned the whole thing. He could have been the developer, the landlord, or the man who passed down a subdivision to his children. That story stuck with my father. He didn’t look at that community and see just houses; he saw the missed potential of a family estate. It instilled in him a property-owning mindset that he passed down to us: When you have the chance to secure the land, you take it.

4. The Gusher and the “Guardian” Trap

In 1913, Sarah’s “worthless” land struck oil. Suddenly, 11-year-old Sarah was generating 2,500 barrels of oil a day. The press labeled her “The Richest Black Girl in America,” but in Jim Crow Oklahoma, a Black child with millions was viewed as a “problem” to be managed.

The most egregious part of Sarah’s story is how the state overrode her family structure. Even though Sarah had two capable, living parents, the Oklahoma probate court appointed a white guardian to oversee her estate. This was a direct assault on the Black family unit; the law essentially stated that a Black father and mother were legally inferior to a white stranger when it came to protecting their own child. Her guardian, T.J. Porter, controlled her accounts and took significant fees while Sarah continued to live in a simple cabin.

5. The “Honorary White” Maneuver

The absurdity reached a peak when the Oklahoma Legislature discussed declaring Sarah “white”. It didn’t happen and it wouldn’t have been a gesture of respect; it was a cynical legal maneuver. By declaring her white, she could ride in first-class trains, but more importantly, it removed the “social friction” of a Black girl possessing more wealth than the white men who governed her.

Furthermore, this was a tactic to allow white men to marry Sarah and steal her wealth. Under Oklahoma’s anti-miscegenation laws, it was illegal for a white person to marry a Black person. By legally turning Sarah white, the legislature was clearing a path for white fortune hunters to wed her and seize control of the “black gold” beneath her feet.

6. The Battle for the Mind: The Competency Trials

As Sarah neared her 18th birthday, legal “grafters” attempted to have her declared mentally incompetent. This was a common tactic: if the state couldn’t steal the land, they would steal the person’s legal agency.

However, Sarah had powerful allies. The NAACP and leaders like W. E. B. Du Bois and Booker T. Washington took notice. They challenged the guardianship in the press and provided a layer of protection. Because Sarah was literate and eventually educated at the Tuskegee Institute, she was able to stand in court and prove she was more than capable of handling her own “two cents.”

7. Mineral Rights: The Geometry of the “Underground”

Many families were tricked into selling their land for a few hundred dollars, not realizing they were selling the rights to the oil beneath it.

Sarah’s family retained their Mineral Rights. In modern terms, this is the equivalent of owning the Intellectual Property (IP) of a business rather than just the office building. You can lease the surface, but if you own the “minerals,” you own the royalty stream forever.

8. Modern Deterrents: The New Guardianship

Today, the “systemic pitfalls” have evolved, but the goal remains the same: to separate families from their equity.

- The Appraisal Gap: Undervaluing homes in Black neighborhoods.

- Heirs’ Property: Developers buying a 1% share from a distant relative and forcing a “partition sale” to seize an entire estate.

- The Probate Tax: High legal fees that act as a “soft” version of guardianship, locking families out of their own inheritance.

9. The Power of the Trust: Protecting Your Legacy

Historically, Black families have relied on Wills. But a Will is a public document that must go through Probate Court. It is an invitation for the state to get involved in your business.

Why Black Families are choosing Trusts over Wills:

- Privacy: A Trust is private. No “oil sharks” can see your assets.

- Control: You name your own Successor Trustee—someone who shares your values.

- Instant Transfer: Assets in a Trust transfer immediately upon death, bypassing the years of legal battles.

10. Conclusion: The “Two Cents” Strategy

Sarah Rector died a wealthy, independent woman because she understood that wealth isn’t just about what you earn; it’s about what the “guardians” can’t take. My grandfather’s story reminds us how easily land can slip through our fingers, but my father’s life showed us how to hold it tight. Build your Trust. Secure your land. Hold your “oil.”

11. Glossary: The Allotment Era & Modern Wealth Protection

To understand the story of Sarah Rector—and to protect your own family’s “two cents”—it is vital to master the terminology of the land. Use this guide as your reference.

- Allotment: The process of dividing communal tribal land into individual private plots. While framed as a gift of ownership, it was often used to dismantle tribal sovereignty and open “surplus” land to outsiders.

- Burke Act of 1906: A federal law that allowed the government to declare a landowner “competent” at any time, effectively fast-tracking the transition of land from tax-exempt trust status to taxable “fee simple” status.

- Competency (Legal Status): A subjective label used by courts to determine if a person was fit to manage their own affairs. In Sarah’s day, this was weaponized to keep Black and Native landowners under the thumb of white guardians or to force their land into the tax system.

- Dawes Rolls: The official list of individuals accepted as members of the Five Civilized Tribes (including the Creek Nation). Being on the “Rolls” determined who received land.

- Fee Simple: The highest form of land ownership, where the owner has full rights to the property. While it sounds ideal, for Sarah’s generation, it meant the land was no longer protected by the federal government and was fully taxable by the local state.

- Freedmen: African Americans who were formerly enslaved by Native American tribes. Like Sarah Rector’s family, many were granted tribal citizenship and land allotments, though their land often faced fewer legal protections against taxation than “blood” tribal members.

- Guardianship (White): A predatory legal system where courts appointed white “protectors” to manage the assets of wealthy Black and Native minors (and some adults), often bypassing living parents and stripping the family of financial agency.

- Heirs’ Property: Land passed down through generations without a formal Will or Trust. Because the title is “tangled” among many descendants, it is highly vulnerable to predatory developers and forced partition sales.

- Mineral Rights (Subsurface Rights): The legal right to own and profit from the resources under the ground (oil, gas, gold). You can own the dirt on top (Surface Rights) while someone else owns the oil below. Sarah’s fortune was secured because her family held both.

- Partition Sale: A court-ordered sale of property that occurs when one co-owner wants to sell their share and the others cannot afford to buy them out. This is a common method used today to take land from Black families.

- Probate: The public, court-supervised process of distributing a deceased person’s assets. It is often slow, expensive, and leaves your family’s wealth open to public scrutiny.

- Restrictions Against Alienation: Legal rules that prevented a landowner from selling or taxing their land for a certain period. Congress removed these for “Freedmen” land in 1908 to allow the state of Oklahoma to collect taxes on oil-rich plots.

- Successor Trustee: The person you name in your Living Trust to take over the management of your property if you pass away or become incapacitated. This is the person you choose—not a judge.

- Trust Patent: The status of land when it is held by the government on behalf of an individual, usually protecting it from taxation and sale.

- Trust Protector: A modern safeguard. This is a third party granted the power to fire and replace a Trustee if they are not acting in the family’s best interest. It is the ultimate “anti-guardian” insurance policy.

Primary Historical References:

- The Dawes Allotment Act of 1887 (General Allotment Act): U.S. Statutes at Large 24:388-91. (The foundational law that broke up tribal lands).

- The Burke Act of 1906: 34 Stat. 182. (The “Competency” amendment that triggered the taxation of land).

- Act of May 27, 1908: 35 Stat. 312. (The specific Congressional act that removed tax restrictions for “Freedmen” land, directly impacting Sarah Rector).

Multimedia & Documentary References:

- “America’s Richest Black Girl: The Sarah Rector Story”: [YouTube Video]. (Reference for the cultural narrative and Taft, Oklahoma context).

- Sarah’s Oil (2025): Directed by Cyrus Nowrasteh. (The cinematic reference point for the modern audience).

Scholarly & Legal Context:

- “The Great Real Estate Scam”: Research regarding the Oklahoma guardianship system and the exploitation of the “Five Civilized Tribes” (Creek, Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, and Seminole).

- “The Bone and Sinew of the Land” by Alyssa Mt. Pleasant: Context on the history of Black and Native land ownership and the struggle for retention.

- NAACP Archives (1913-1914): Reports on the investigation into the welfare of Sarah Rector, spearheaded by W.E.B. Du Bois.