During one of my recent family gatherings, my nieces, one who is currently in college and the other who is a budding entrepreneur, told me how they decided to take a summer course that trained individuals to be EMS technicians. They told me all about their various experiences riding with trained EMS workers as they drove around the city responding to emergencies. The one who is the entrepreneur was so inspired that she is currently studying to be an Emergency Medical Services (EMS) technician. I was struck by the complexity of the procedures that she’s learning and the sheer responsibility she’s preparing to take on. It truly is one of the most important jobs in the world. The impact of modern EMS is undeniable: today, EMS personnel save countless lives, particularly in cases of Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OHCA). Annually, there are over 350,000 OHCA events in the U.S., and while survival rates remain challenging, bystander CPR and immediate professional intervention are critical, with survival rates to hospital discharge hovering around 10.4% for adults, a number that translates to thousands of lives saved and neurological function preserved.

This advanced, professionalized system is a direct legacy of the Freedom House Ambulance Service (FHAS). Its story, however, is not just one of medical innovation; it is a profound lesson in how social justice movements created essential services that were often neglected by the state, only to see those services eventually coopted by the very municipal governments that had initially failed their communities.

Section 1: A Dual-Purpose Vision Born of Neglect and Partnership

The FHAS was born out of two simultaneous crises: the national inadequacy of pre-hospital care exposed by the 1966 “White Paper” (Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society), and the racially motivated neglect of essential services in predominantly Black urban areas.

The Failure of the State

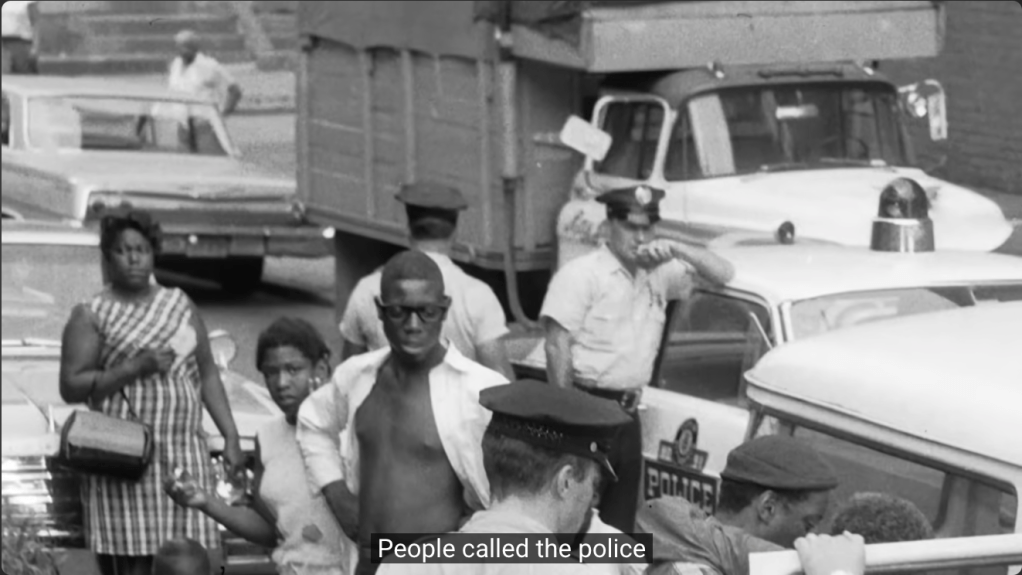

In the late 1960s, Pittsburgh’s predominantly African American Hill District was starved of reliable emergency services. As was common across the country, people called the police, and there weren’t ambulances as we think about them today. Police cars (paddy wagons) or hearses from funeral homes served as ambulances, staffed by individuals with little to no medical training. For African American citizens, this already poor system was compounded by slow response times, and “relations between the police and the black community were oppressive”.

Former Hill District resident and future FHAS paramedic, John Moon, recounted a traumatic personal experience illustrating this neglect:

“I found my mom laying on the floor… two police officers showed up and said she was drunk and they were not going to transport her to the hospital. You never knew how it was going to turn out. It was a gamble”.

Moon was forced to carry his sick mother down the stairs and put her in a police paddy wagon, which was the same vehicle they used to transport dead bodies and people they arrested, only to have her die five days later from a cerebral hemorrhage.

This institutional neglect mirrored the systemic abandonment seen in many urban communities, which fueled the creation of self-sufficiency movements. Just as organizations like the Black Panther Party (BPP) were established to fill the vacuums left by the state by creating “Survival Programs” like Free Breakfast for Children and Free Health Clinics, the Hill District’s community leaders recognized they had to create their own life-saving emergency medical response.

The Architects of Change and The Essential Partnership

The solution was not solely introduced by the medical establishment, but emerged through a pivotal, intentional, and strategic partnership addressing the “dovetailing needs” of the community for both better healthcare and employment opportunities.

The final successful program was the result of a deliberate collaboration where each party supplied a critical missing piece:

- Phil Hallen and the Maurice Falk Medical Fund (Social/Financial Initiative): Hallen, the director of the fund and a former ambulance driver himself, played the initial role of recognizing the opportunity to address both the health disparities and the economic distress in the Hill District simultaneously. He was the one who conceived the idea of creating a new ambulance service centered on job creation for unemployed African Americans and sought out the necessary medical and community partners.

- Dr. Peter Safar (Medical Vision): Safar, the “Father of CPR,” supplied the crucial medical expertise. Driven by the recent tragic death of his 11-year-old daughter, Elizabeth, he was desperate to prove his theory that non-physician personnel could be rigorously trained to deliver Advanced Life Support (ALS) in the field. Dr. Safar believed that people “they marked unemployable was really just waiting on opportunity”. Safar was essential for creating the medical curriculum and standards.

- James McCoy Jr. and Freedom House Enterprises (Community Structure): McCoy, founder of Freedom House Enterprises, was the key community leader who provided the organizational structure, local knowledge, and the pool of recruits from the Hill District. The existence of Freedom House Enterprises, an agency dedicated to civil rights, job creation, and filling service gaps, meant that the community was primed and organized to take ownership of this essential life-saving service. The partnership fit perfectly within its mission of self-reliance and community empowerment.

The recruits—African American men and women from the underserved community—were transformed from citizens often labeled “unemployable” into the nation’s first professionally trained paramedics.

Section 2: The Revolutionary Model and Breakthroughs

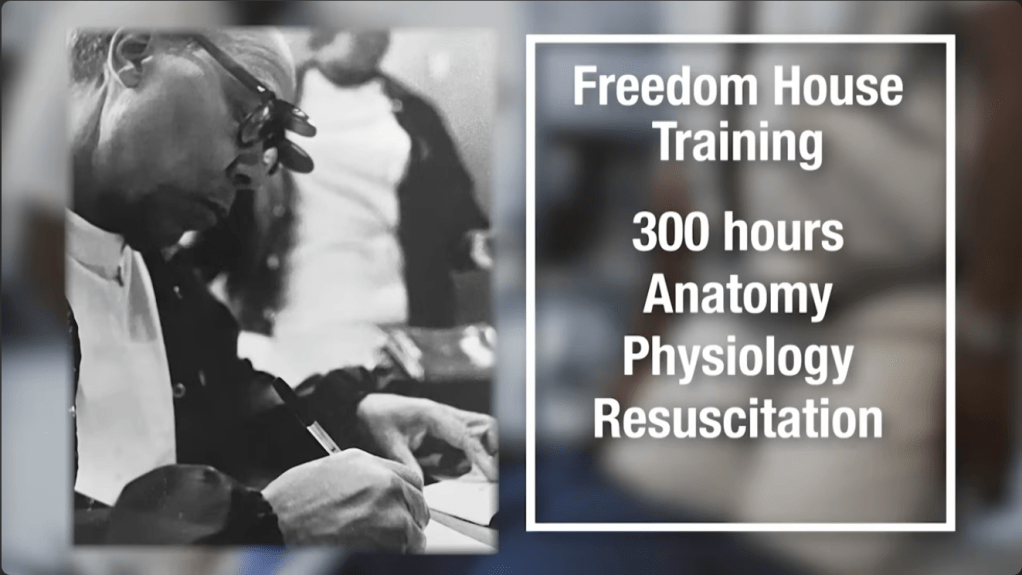

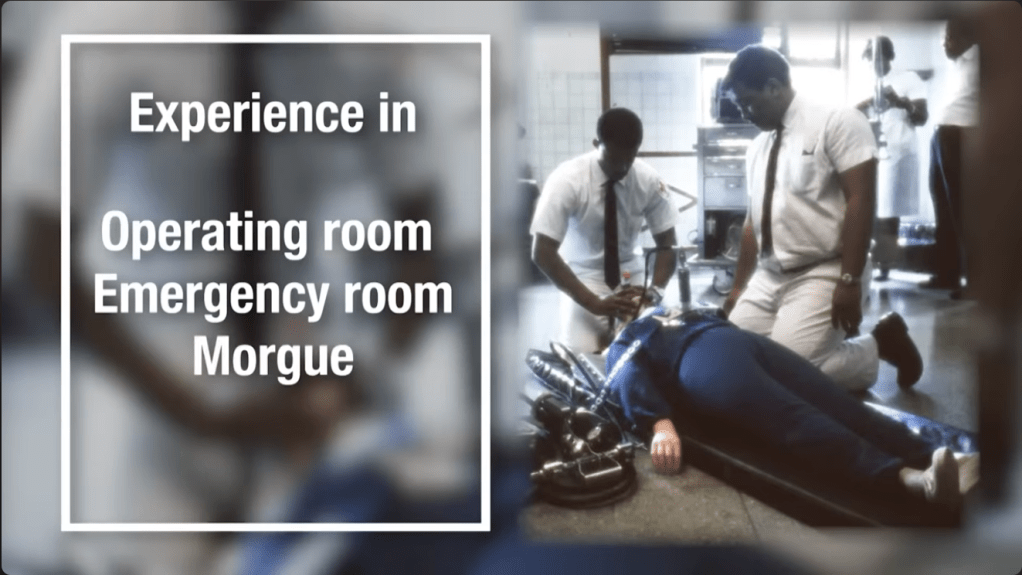

The 32-week, 300-hour curriculum designed by Dr. Safar and Dr. Nancy Caroline set a new national standard. The training was comprehensive, including classroom instruction, anatomical studies, and clinical rotations in emergency rooms.

Pioneering Field Medicine

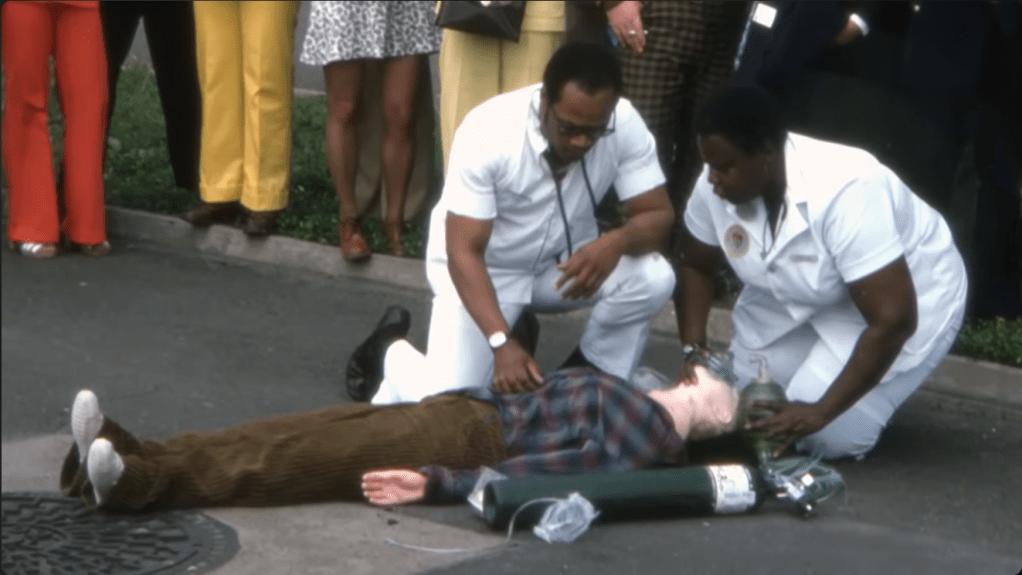

The FHAS paramedics proved that complex, life-saving techniques could be developed and administered in the field, effectively turning their ambulances into mobile emergency rooms. Their breakthroughs in pre-hospital care include:

- Intubation: Performing the first documented endotracheal intubation in the country on a patient outside of a hospital setting to secure a critical airway. FHAS paramedic John Moon recalled his first successful field intubation, stating, “she [Dr. Caroline] was overjoyed… and from that point on it was normal”.

- Defibrillation and Cardiac Care: Administering electric shocks to cardiac arrest patients, making pre-hospital defibrillation a reality.

- IV Therapy and Pharmacology: Establishing intravenous access and administering essential drugs like Narcan for overdoses.

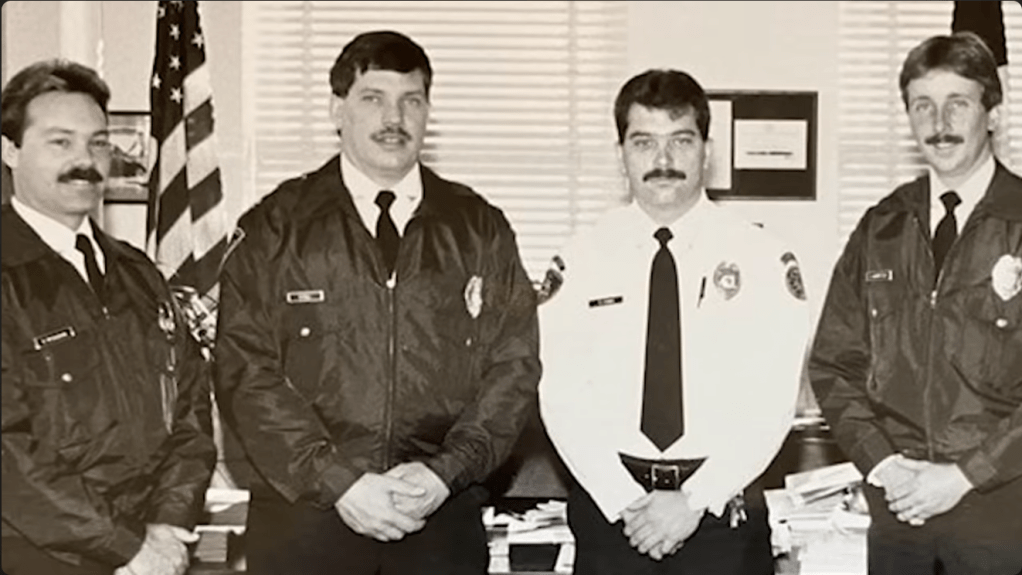

These techniques were not merely transportation; they were life-saving techniques developed for the field that directly addressed the preventable deaths highlighted in the White Paper. FHAS paramedic George McCarey III, one of the original class members, captured the powerful impact: “My first memory of Freedom House was people coming to take you to the hospital that looked like you that understood you”. The service brought a true “sense of pride and dignity to the community”.

The FHAS paramedics saved hundreds of lives, and their superior care became renowned, with even police officers and people in other neighborhoods requesting their assistance. In one instance recounted by a former medic, a police officer bypassed a dispatcher’s refusal to send Freedom House outside their district for a child hit by a bus, telling the dispatcher, “you need someone out here that knows what the hell they’re doing”.

The Connection to 9-1-1

While the system was independently created, the successful, high-quality, and rapid response demonstrated by FHAS, alongside other national pilot programs, provided the operational proof of concept necessary to justify the creation of a universal emergency response infrastructure. The need for a centralized, professionally staffed system was cemented by the FHAS model, directly influencing the standardization of EMS training and the widespread adoption of the 9-1-1 emergency telephone system.

Section 3: Cooption, Resistance, and The Forgotten Legacy

Like the Black Panthers’ Free Breakfast Programs—which were so successful, the government created its own, often inferior, version—the FHAS was ultimately coopted by the city administration.

The Political Demise

The existence of a superior, community-controlled, and Black-staffed EMS was a political embarrassment and a challenge to the power structure. The city’s Mayor, Pete Flaherty, disliked that the service was something “he had not created, he had no control over”. This political conflict intensified because residents in more affluent areas of Pittsburgh were getting frustrated that poor people in the Hill were receiving better emergency care than they were.

Despite the overwhelming evidence of the service’s success, the City of Pittsburgh, under Mayor Flaherty, refused to renew the FHAS contract in 1975. John Moon recalls the mayor’s pettiness, being called in and asked if the ambulances could use a bell, “like an ice cream truck”, instead of a siren, a moment Moon realized was the “beginning of the end”. The city then launched its own municipal EMS service.

The Freezing Out of Pioneers and Deputy Chief Gilchrist

The transition was marked by institutional racism. When the new city service was formed, it was initially staffed by a predominantly white workforce. The experienced African American FHAS paramedics were frozen out: they were forced to reapply, were “tested on a weekly basis”, and Moon stated they “entered into a program that was designed to systematically eliminate as many of Freedom House’s employees as they possibly could”. Their pioneering experience and institutional knowledge were dismissed.

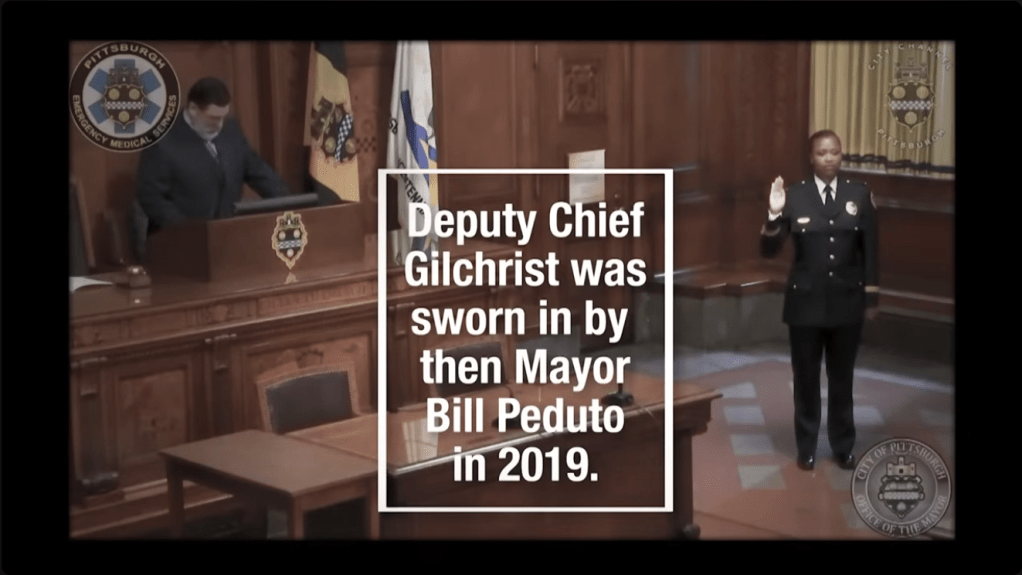

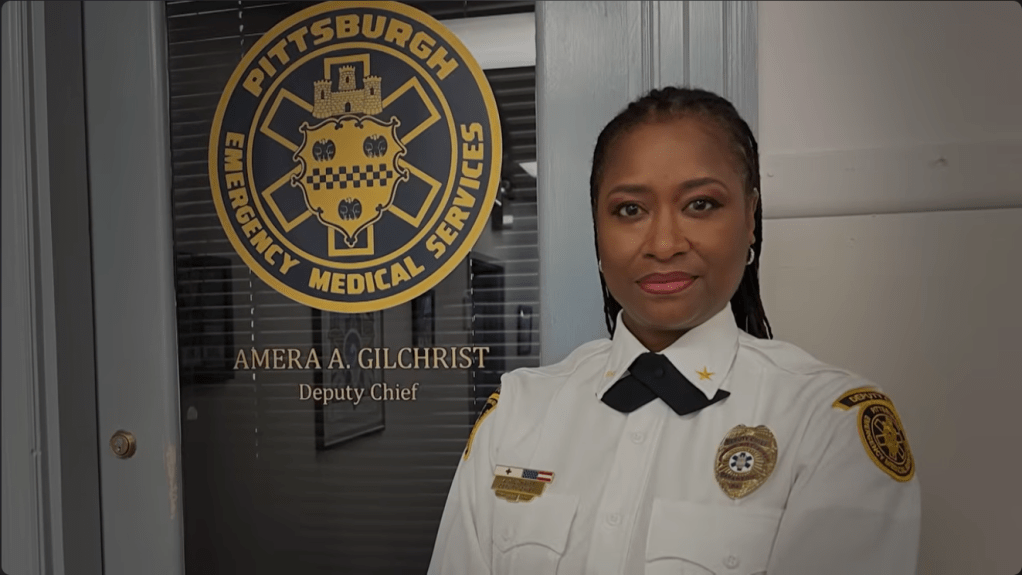

The legacy of the FHAS, however, eventually found its culmination in the career of Amera Gilchrist. She approached John Moon, who had survived the transition and was then responsible for hiring, expressing her desire to work for the City of Pittsburgh EMS. Gilchrist was a highly motivated recruit who gradually rose through the ranks.

In a powerful moment that validates the perseverance of the original FHAS paramedics, Amera Gilchrist became the Deputy Chief of the City of Pittsburgh EMS, the first African-American to hold the title. She acknowledged her debt to the founders of the FHAS, stating that she would not have achieved that position “but for the shoulders of the Giants that I stand on who are the members of Freedom House”.

The legacy of the Freedom House Ambulance Service, though almost lost to history, survives as the essential blueprint for all modern EMS and paramedic training in the United States, forever linking the fight for racial equity with the foundation of modern emergency medicine.

You can learn more about the Freedom House Ambulance Service’s story and its impact on modern EMS in this video: Freedom House Ambulance: The FIRST Responders | America’s First EMT Service.