Contents:

- Intro

- The Canvas: Built on an Unmarked Default

- The “Cultural Closet” and Erased Contributions

- The Financial Subsidy of Whiteness

- The Structural Tear: The Civil Rights Catalyst

- The Defensive Wall: Colorblindness as a Guardrail

- The Organized Backlash: Pulling Back the Gains

- A. Institutional Retrenchment (Voting Rights)

- B. Cultural Containment (Anti-CRT/DEI)

- Conclusion

Intro

I recently wrote an article discussing ways to address reparations. The conservative response was numerous, agitated, and often violently angry. While the topic of reparations is important, my current article is driven by the thought that what is truly needed is the dissipation of the idea that colorblindness is the solution to racism. The hostile reactions I received—many of the responders called me “racist” just for mentioning race—reveal the fundamental blockade: the aggressive avoidance of any discussion that acknowledges race as a factor in American society.

This resistance is not random; it’s an organized defense of the societal structure where whiteness has long functioned as the invisible default—the unspoken, universal standard of what is “normal.” When that default is challenged, the reaction isn’t surprising; it’s the defense of the “white canvas.”

1. The Canvas: Built on an Unmarked Default

The foundation of this “white canvas” is rooted in the nation’s founding. The Founding Fathers actively operated in a functionally “colorblind” manner when creating the Constitution, not because they saw all people equally, but because “white” was already the default. The approximately 500,000 Black slaves, deemed inhuman, had no voice. Free Black people were inconsequential to the power structure. In my opinion, the Founders underestimated or never dreamed of the power of a living document that had the capacity to adapt to change through amendments. The enduring concepts they created—such as liberty and justice—remained the document’s power, but the amendments profoundly changed who was envisioned as the recipient of these concepts. The current battle isn’t against the original Constitution, but against the corrective power of the amendments that expanded the concepts to include Black citizens.

Since then, the assumption has persisted: whiteness is the baseline, and everything else requires a racial qualifier. A film with an all-white cast is simply “a movie,” but a film with a majority Black cast is always a “Black movie.” This pervasive norm operates like an invisible set of privileges—unexamined benefits that feel like simple normalcy—until they are actively displaced by non-white representation.

The “Cultural Closet” and Erased Contributions

Some argue that any talk of systemic racism is overstated because of the acceptance of Black culture in America and the globe. However, this acceptance often functions less as inclusion and more as a fetishization. The resistance is not to the culture itself, but to the assertion of Black presence as the unquestioned norm in a shared space. I witnessed this firsthand when a drawing by my son, depicting the historical Black community of Weeksville, Brooklyn, featuring exclusively Black figures, was removed by the buyer from their office. The buyer explained that the image made some white colleagues uncomfortable. Had the art depicted a white historical scene, it would have been neutral decoration. But because it asserted Black normativity, it was viewed as a disruptive “stain.” This dynamic reveals the truth of the “white canvas”: it is as if white America has a colorful canvas hidden away in the closet: when they want to enjoy Black art, music, athletes, and entertainers, they bring it out. But when serious guests arrive, or when the conversation turns to politics and equity, they hide it away again.

This selective consumption is possible because the foundational contributions of Black people are systematically ignored. Many white Americans ignore, or worse, don’t know, that items used in their households and even their daily lives were created or improved by Black inventors, proven by the numerous patents they hold. By consuming the culture while erasing the inventor and the citizen, the “white canvas” maintains a comfortable distance: it enjoys the fruit but denies the root.

The Financial Subsidy of Whiteness

Crucially, the “white canvas” is not merely a cultural artifact; it is a system of subsidized privilege and wealth transfer. This system, historically maintained through policies like redlining and discriminatory banking practices, has artificially inflated the generational wealth and home equity of white communities, while simultaneously depressing the economic potential of Black neighborhoods. Therefore, the resistance to changing the canvas is not just about cultural comfort; it is about actively protecting these accumulated, tangible financial assets and the structural advantages built upon generations of unequal access. The defense of white normativity is, ultimately, a defense of an economic safety net subsidized by racial exclusion.

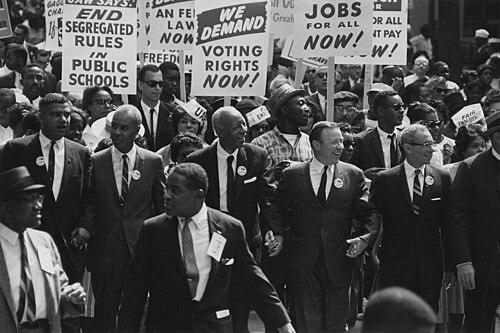

2. The Structural Tear: The Civil Rights Catalyst

The invisible canvas was first fundamentally torn by structural policy, specifically the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

This Act was the structural catalyst that provided Black Americans with quantifiable access to high-wage jobs and quality education, integrating them into institutions traditionally reserved for white citizens. The data is clear: the high school completion rate for young Black Americans surged from just 25% in 1964 to 85% by 2008. These gains fostered a growing Black middle class, ensuring Black presence was no longer confined to marginalized spaces but began to occupy positions of visible influence.

This transformation first appeared in culture—from the dominance of Tiger Woods in golf and the Williams sisters in tennis, both historically white-dominated sports—but the ultimate reality check came in 2008 with the election of Barack Obama. Placing a Black man at the absolute pinnacle of institutional power turned abstract cultural anxiety into concrete political fear over the disappearance of the white norm.

3. The Defensive Wall: Colorblindness as a Guardrail

As the canvas changed, a powerful defensive ideology was activated: “colorblindness.”

While proponents claim it’s the solution to racism, it actually functions as a rhetorical guardrail designed to protect white privilege. As sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva notes, this color-blind racism attempts to halt any descriptive analysis of the existing racial hierarchy. When you bring up systemic issues and someone immediately calls you “racist” for mentioning race, they are attempting to silence the conversation necessary for structural change. If the act of naming systemic racism is deemed unacceptable, the white default remains unexamined and undisturbed.

The final rhetorical stage of this defense is the weaponization of victimhood. When the discomfort of losing the privileged default becomes too great, it is reframed as “reverse racism,” converting the loss of unearned status into a claim of oppression. This strategic inversion allows the dominant group to label any attempt at equity as an attack, providing the moral justification needed to demand a restoration of the old canvas.

4. The Organized Backlash: Pulling Back the Gains

The psychological stress of the “staining of the white canvas,” reinforced by the financial need to protect subsidized privilege, has translated into organized political agitation fueled by racial resentment—the modern belief that Black people now receive undue advantages and that racism is a solved problem. This resentment justifies a concerted effort aimed at rolling back the structural gains catalyzed by the Civil Rights Act.

This backlash operates through two major projects:

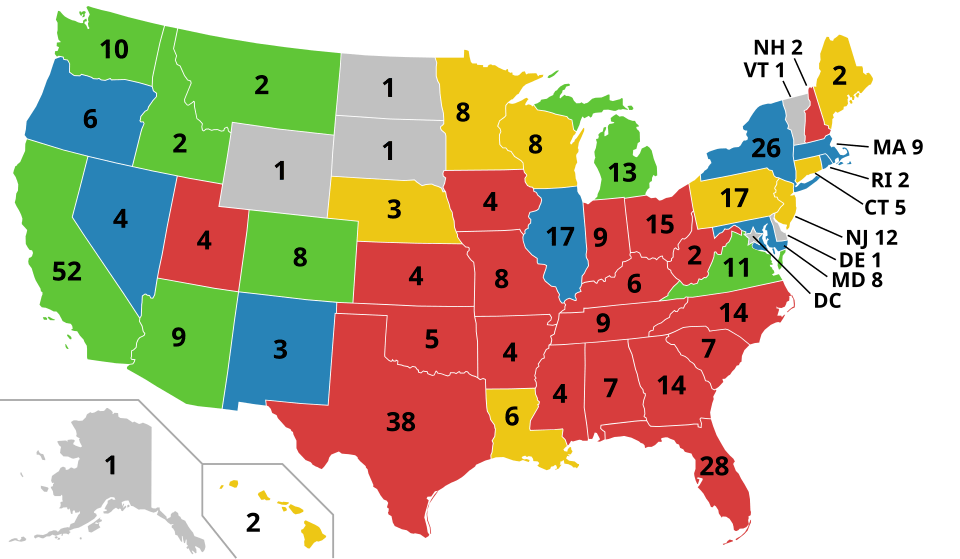

A. Institutional Retrenchment (Voting Rights)

This project aims to limit political access. The effort gained speed after the 2013 Supreme Court decision in Shelby County v. Holder, which dismantled key federal oversight of the Voting Rights Act. States immediately responded with restrictive Voter ID laws and polling place closures that systematically target minority communities. The ongoing practice of racial gerrymandering, such as the strategic redrawing of legislative districts in Texas to fracture and lessen the voting power of Black neighborhoods, is a clear extension of this project. These actions are a systemic attempt to restore the political boundaries of the old canvas.

B. Cultural Containment (Anti-CRT/DEI)

This project seeks to ban the frameworks needed to discuss race. The coordinated political campaigns against Critical Race Theory (CRT) and Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion (DEI) are fundamentally color-blind strategies of containment.

These movements are often fueled by nostalgia for a mythological past—a time before the Civil Rights Act—when the “white canvas” was unquestioned. By controlling the curriculum and banning frameworks that teach accurate, systemic history, advocates of the old canvas seek to preserve a fictionalized narrative where the nation’s founding was perfect and inequality is the result of individual failure, not structural design. By framing concepts that analyze systemic power as “divisive,” the goal is to eliminate the descriptive language needed to even identify the existence of the “white canvas.” This ensures that white normativity remains an unexamined, unquestionable default in our schools and workplaces.

Conclusion

The modern racial tension in America is a sustained, multi-layered political defense of white normativity against the structural and symbolic threats initiated by the Civil Rights Act and codified through the power of the amendments. The quantifiable gains of the Civil Rights Act provided the access; the election of Barack Obama provided the symbolic shock; and the ensuing political agitation represents a desperate, organized imperative to halt the staining of the “white canvas.” The political utility of “colorblindness” today is not a path to equality, but the final, sophisticated defense of an American social landscape that is irreversibly changing color. America will be where it needs to be when the colorful canvas currently hidden away in the closet is finally hung in full display.