Contents:

- Introduction

- Purity vs. Practicality in Politics

- Why We See the World Differently

- The Real Crisis: Money vs. Mercy

- The Ancient Rule: Welcoming the Stranger

- The Modern Test: The Dollar’s Price

- Final Thoughts: What We Really Value

Introduction

I recently had an unexpected, deep discussion about religion and politics with a friend, only to discover that they support the current Republican administration. While I’m familiar with these conservative viewpoints from my Southern Christian family and other friends, those previous conversations were always with my white friends.What made this conversation different is that this friend is Black and brings a very different point of view and that I have known him for a very long time and never knew he felt this way. As we got deeper into the discussion It was clear that his main reason for backing them was his belief that their policies line up better with his Christian faith. I told him that as a Christian myself, I tend to vote Democrat because I believe they show more practical empathy for people who are struggling..

Purity vs. Practicality in Politics

His very first objection, a common refrain among conservative Christians, was that the Democratic Party allows all kinds of “foolishness” and morally unacceptable behavior into its ranks.

The irony is that Jesus’s ministry was built on embracing those the religious community shunned. His business was the outcasts. He spoke with the woman at the well, didn’t judge her lifestyle, and gave a powerful warning to those who stood on the outside passing judgment: “He who is without sin, let him throw the first stone.” To bring that level of purity test into the political arena, I believe, fundamentally misinterprets the Christian calling.

The government’s role is secular. Its job is to manage the welfare and safety of all its citizens, not to enforce moral code. I already have a pastor to guide me spiritually; I don’t need a president to assume that role. A government must serve everyone, and not every citizen is a Christian.

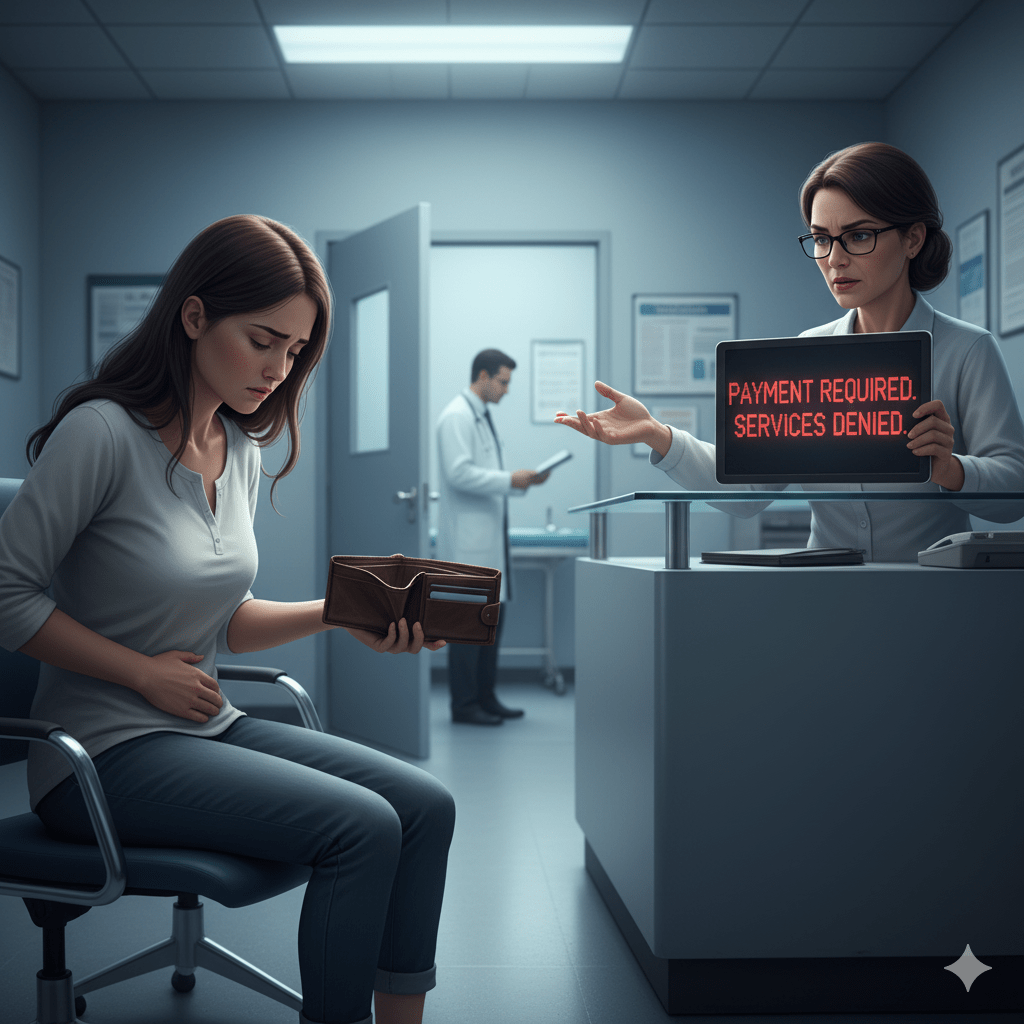

Despite our differing views on the role of government, the debate eventually came to a head when he asked me, out of the blue, “What did Obama ever do for poor people?” I quickly said, “The first thing I think of is affordable health care.” He totally disagreed, arguing, “Healthcare was always available to anyone who wanted it.” He used his own story as proof: he came here in 1999, got insurance without a problem, and truly believes that if you just work hard, you can get whatever you want in America.

Why We See the World Differently

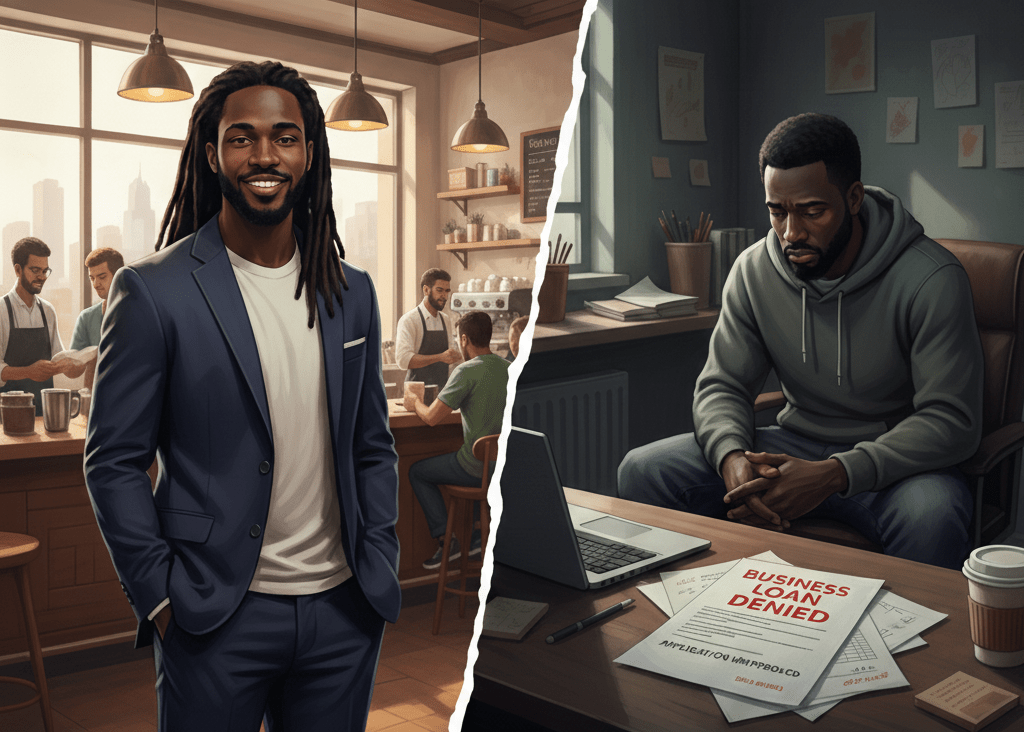

My friend’s belief that success is solely about hard work is a huge part of the American Dream. But his experience, especially as a Black Caribbean immigrant, actually reveals a much more complicated truth about the American system.

His hard work is undeniable, but the path for Black immigrants, particularly those from the Caribbean entering primarily through family channels, is fundamentally different from the path for African Americans. Crucially, the path also varies greatly within the immigrant community itself: While many African immigrants are often pre-selected as highly educated professionals, Caribbean immigrants often rely on family ties. This happens because immigration laws use “positive selection,” favoring those with higher education and skills—for instance, many African immigrants arrive through selective programs, making them statistically one of the most educated groups in the U.S. Caribbean immigrants, however, more frequently enter through family reunification, leading to a much wider range of educational backgrounds. His success, therefore, strongly reinforces his belief in the “bootstraps” story.

The problem is this focus on individual effort ignores American history’s systemic baggage. African Americans carry generational trauma and were systematically blocked from building wealth through policies like segregation and redlining. When immigrants arrive without that institutional deficit, they sometimes tragically assume that African Americans are struggling because they are lazy or just looking for “handouts.” This hurtful idea—that success requires pushing down others—is a dangerous, adopted step in the assimilation process for many immigrant groups.

The Real Crisis: Money vs. Mercy

This brings us to the central question we face as a nation: How much has America’s singular pursuit of capitalism damaged our empathy?

My friend’s success is real, but it doesn’t erase the flaws the Affordable Care Act (ACA) tried to fix. Before the ACA, insurance might have been available, but it was unaffordable for millions. Worse, people could be legally denied coverage just because they were sick and had pre-existing conditions. The ACA stopped that discrimination and provided subsidies so working families could finally afford to stay healthy. This shows that the lack of health care wasn’t a failure of effort; it was a failure of the economic system.

Given America’s massive wealth, providing basic care shouldn’t be a struggle; it should be simple. The obstacle isn’t a lack of resources—it’s greed. Conservatives claim that America is a Christian nation, but their economic policies often violently clash with spiritual duty. This conflict is how Kendrick Lamar connected his rap song, “how much a dollar cost”, to the Bible.

The Ancient Rule: Welcoming the Stranger

The scripture Hebrews 13:2 gives a clear, timeless command: “Be not forgetful to entertain strangers: for thereby some have entertained angels unawares.”

This scripture isn’t just about being polite; it’s a spiritual warning. It asks you to treat every vulnerable person—every stranger—with dignity because they might be something divine. It’s a call to charity that demands no condition, no judgment, and no calculation of risk.

The Modern Test: The Dollar’s Price

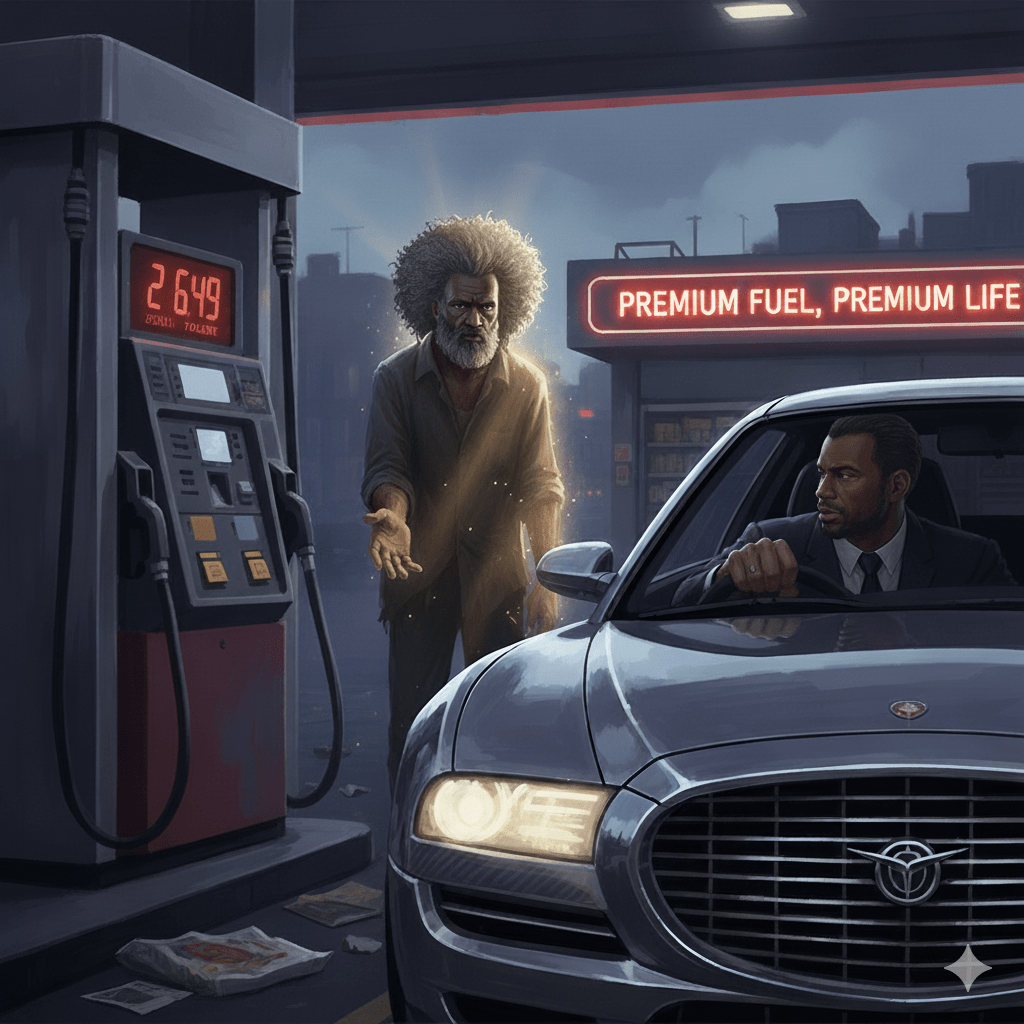

Kendrick Lamar’s song, “How Much a Dollar Cost?” (click for lyrics) is the perfect modern test of this rule. The successful narrator, feeling untouchable in his luxury car, is confronted by a homeless man. The narrator is instantly suspicious, judgmental, and defensive, concluding, “Every nickel is mines to keep.”

Crucially, the homeless man asks for ten Rand, a tiny, almost worthless amount of South African currency. The monetary cost is negligible, showing the narrator’s refusal isn’t about saving money; it’s about pure greed—a refusal to share even the slightest amount. Just as it would be effortless for Kendrick to spare the Rand, America’s failure to care for its needy is not a matter of resource constraint, but is also a matter of greed.

The song ends with the chilling reveal: the man is God, the Messiah. He tells the narrator the real price of the dollar: “The price of having a spot in Heaven, embrace your loss—I am God.” The literal price of ten Rand was nothing, but the moral cost of refusing it was everything.

Final Thoughts: What We Really Value

The contradiction is clear: How can a political movement champion a return to religious values, like prayer in schools, while actively fighting the programs that embody the most fundamental Christian mandate—caring for the poor?

My friend believes the poor just need to work harder, but the premise of the scripture and the shock of Kendrick’s song is that true morality requires extending grace without condition. When a political platform prioritizes economic competition and self-reliance over guaranteeing basic necessities like affordable health care, it is choosing the idol of the dollar over humanity. In this framework, America is forgetting to entertain the stranger because its capitalist system has taught it that every dollar given is lost, forgetting that sometimes, the dollar you give is the only way to save yourself. This is the terrible irony of a political movement that prioritizes economics above all else: by teaching citizens to fear the loss of every nickel, the system risks finding itself, like the man in Kendrick’s car, face-to-face with the divine, having paid the full, unbearable price of self-interest.