Contents

- Introduction

- The Deep Roots of Early American Wealth: Slavery, Agriculture, and Presidential Endorsement

- The Early Booms: Building America, But Not for Everyone (and the Social Toll)

- The Golden Era: Prosperity, Social Unity, and Shifting Global Dynamics

- Periods of Peril: Economic Struggles, Societal Strain, and Policy Limitations

- The Modern Era: Navigating Crises, Societal Divides, and the Push-Pull of Economic Ideologies

- The Bottom Line: Promises vs. Reality, and Who Benefits

- Conclusion

Introduction

You know how every election year, politicians stand up and tell us how their policies are the magic key to a booming economy? Republicans promise tax cuts and deregulation; Democrats talk about government investment and social safety nets. They lay out grand visions, often making it sound like their party alone holds the secret formula for prosperity. Well, if you look back at American history, the truth is a lot messier and more fascinating.

Though I am an engineer by profession I have an undying love for history. It is rare that I give an opinion on anything that the basis is not my understanding of its history. In this paper I will discuss the American economy from the perspective of past presidents in relation to the classic principles of their perspective parties. I will draw much of my information from my research for a paper that I have been writing for a while on Presidents and how their policies effected their period of history.

The economy’s a wild ride, and whether it’s soaring or sputtering depends on a whole slew of things: what the president does, sure, but also what’s happening around the world, the particular mood and makeup of society at that moment, and crucially, who’s actually feeling the good times (or bearing the brunt of the bad).

This paper isn’t just a dry list of facts; it’s a stroll through time, a detective story of sorts, trying to figure out why some periods hummed with prosperity and why others plunged into hardship. We’ll dig into how different presidents, guided by their party’s philosophies, made choices that shaped the nation’s finances. But we’ll also pay close attention to the social vibe of each era – what people cared about, who had power, and who was left out – because that dramatically influenced how policies played out and who truly benefited. And we can’t forget the global stage: wars, oil crises, new technologies emerging worldwide – these external forces often hit America like a tidal wave, sometimes pushing us forward, sometimes knocking us off course.

By looking at these complex interactions, we can really figure out if those bold campaign promises hold up when measured against the messy, unpredictable reality of America’s economic past. It’s about understanding that economic success or failure is rarely the singular achievement or fault of one person or one party, but rather a dynamic dance between many powerful factors. I will select some of America’s more successful eras and some of its worst. I will use this discussion to dispute the idea that republican or democratic policies alone determine the economic success or failure of any one president.

The Deep Roots of Early American Wealth: Slavery, Agriculture, and Presidential Endorsement

Before the grand industrial booms that defined later centuries, it’s critical to acknowledge that the agricultural period, fundamentally built on the institution of slavery, was crucial in propelling America as a significant global economic power. This era, particularly from the late 18th century through the mid-19th century, saw the U.S. emerge as a significant global economic player, driven by crops cultivated through forced labor.

The period following the Revolutionary War, under early presidents like George Washington (Independent, then Federalist-leaning) and Thomas Jefferson (Democratic-Republican), saw the nascent nation grappling with its economic identity. While Washington’s administration, particularly under Alexander Hamilton, laid foundations for national finance and manufacturing, the economic engine increasingly became the South’s plantation system. Under Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican presidency, policies like the Louisiana Purchase (1803), while expanding the nation geographically, also dramatically expanded the territory available for slave-based agriculture, particularly cotton cultivation. This monumental land acquisition, an executive decision, directly contributed to the spread and intensification of the plantation economy.

By the early to mid-19th century, under a succession of Democratic presidents like Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk, the economic dominance of “King Cotton” was undeniable. These presidents often represented a political party strongly aligned with Southern agrarian interests. Their administrations, while not necessarily issuing direct “policies” to create slavery (which predated the republic), certainly enacted and upheld legal frameworks that protected, facilitated, and expanded the institution of slavery within the growing nation. This included defending states’ rights over federal interference in slavery, promoting westward expansion into territories ripe for plantation agriculture (like the annexation of Texas under Polk), and enforcing federal laws like the Fugitive Slave Act.

The immense wealth generated by this system was staggering. Cotton, cultivated by enslaved people, became the most important American export by far, directly fueling the textile mills of Great Britain and New England – the industrial powerhouses of the era. This made the American South, and thus the U.S. economy, an indispensable part of a global supply chain. The profits from cotton (and other slave-produced commodities like sugar, tobacco, and rice) created significant wealth for Southern planters and, through extensive trade networks, for Northern merchants, financiers, and shippers.

This wealth was then reinvested in various sectors of the American economy, including infrastructure (like canals and railroads that aided cotton transport), land, and even early manufacturing ventures. The enslaved individuals themselves were viewed as property and represented a massive amount of capital; their forced labor effectively provided “free” labor, allowing for production at extremely low costs and generating enormous profits that could be leveraged and invested, underpinning a significant portion of early American credit and finance.

Socially, this era was characterized by a profound and violent paradox: immense wealth and the promise of “liberty” for some built directly upon the brutal dehumanization and enslavement of others. The social climate of the South was a rigid hierarchy enforced by violence, with white male landowners at the top and enslaved people at the bottom. In the North, while slavery was abolished, many profited indirectly from its wealth, leading to a complex and often hypocritical stance on the issue. The national political discourse became increasingly dominated by the issue of slavery’s expansion, laying the groundwork for the Civil War.

Economic Impact on Society: For the white landowning elite in the South, this system brought immense riches and political power. For Northern merchants and financiers involved in the cotton trade, it brought significant profits. However, for the millions of enslaved African Americans, the “economic success” of this period meant uncompensated forced labor, brutal violence, family separation, and the denial of fundamental human rights. Their forced contribution built the nation’s wealth but offered them nothing. For white yeoman farmers in the South without slaves, opportunities were often limited by the dominance of slave-based plantations. This period of foundational wealth creation, therefore, represents a profound stain on America’s economic history, demonstrating how a singular focus on aggregate economic metrics can mask immense human suffering and fundamental injustice. It also directly contributed to the deep sectional divisions that eventually led to war, highlighting how an economic system built on such profound social inequity is inherently unstable.

The Early Booms: Building America, But Not for Everyone (and the Social Toll)

After the immense human cost and destruction of the Civil War, America rolled up its sleeves and went on a massive building spree. The Post-Civil War Industrial Expansion (roughly 1865-1873) was a pivotal moment, showing the nation’s incredible potential for growth but also exposing its raw inequalities. Under President Andrew Johnson (a Democrat who followed Lincoln) and then Ulysses S. Grant (a Republican general-turned-president), the country embarked on a period of intense industrialization.

From a policy standpoint, both administrations, broadly speaking, continued or supported initiatives aimed at knitting the vast country together. Think of the transcontinental railroads, which weren’t just private ventures; they were often backed by significant federal land grants and subsidies. These policies weren’t just about moving people and goods; they were about opening new frontiers, facilitating the movement of raw materials to burgeoning factories, and creating entirely new markets for American industries. This was about rapid expansion, about connecting the East to the West, and about building a unified national economy. The prevailing social climate was one of intense, often fraught, national reunification. There was a powerful drive to rebuild what was lost and to push westward, fueled by a belief in Manifest Destiny – the idea that America was destined to expand across the continent. This drive, however, often came at the expense of indigenous populations.

External factors weren’t as globally interconnected then as they would become, but the sheer abundance of natural resources within the U.S. (coal, iron, timber) and a growing labor force (swelled by returning soldiers and a fresh wave of immigrants from Europe) provided the essential ingredients for this expansion. Internal factors like an intense entrepreneurial spirit, crucial technological innovations (like improved steel production techniques that made building railroads and skyscrapers more efficient), and the increasing availability of capital for investment (both domestic and from Europe) were the foundational engines of this early boom.

Who felt it, and how did society react? This period undeniably laid the groundwork for America’s future industrial might. Railroad tycoons, industrialists, and powerful financiers like Jay Gould and Cornelius Vanderbilt amassed colossal fortunes, becoming the titans of American business. For many returning soldiers, particularly white veterans, and adventurous migrants, it offered new opportunities in frontier towns or rapidly industrializing cities. However, the benefits were astonishingly unevenly distributed, and this laid the foundation for deep social divisions.

For African Americans, despite emancipation, the reality was stark. They faced overwhelming systemic discrimination, the rise of Jim Crow laws, and often found themselves trapped in oppressive sharecropping systems that amounted to economic peonage. This severely limited their access to the new economic opportunities flowing through the nation. Native American populations, often seen as obstacles to westward expansion, suffered immensely, facing forced removal, violence, and the destruction of their traditional ways of life as settlers pushed onto their ancestral lands. Meanwhile, laborers, particularly in the burgeoning factories and mines, endured horrifying working conditions: long hours (often 10-12 hours a day, six days a week), dangerous machinery, child labor, and shockingly low wages. They had virtually no legal protections or safety nets.

America missed a significant opportunity for greater economic growth by actively suppressing the economic development of African Americans. Instead of integrating the newly freed population into the nation’s burgeoning economy, systemic racism and oppressive policies created profound barriers. The promise of “40 acres and a mule” was never fulfilled, and in its place, African Americans were provided little chance for wealth accumulation. While Black communities, through immense resilience, (with no help of government provided social programs) managed to build thriving towns and business districts—such as the Greenwood district in Tulsa, Oklahoma, famously known as “Black Wall Street”—these centers of economic power and innovation were often met with violent attacks. The destruction of these communities prevented them from developing into regional economic hubs that could have contributed to America’s overall wealth, talent, and growth. This systemic prevention of Black economic progress not only perpetuated racial inequality but also held back the nation’s full economic potential.

Imagine how greater the American narrative could have been. That a people that were once slaves could in a mere 30 years after emancipation could have their own towns, be political leaders, and business owners, all contributing to the American dream. What a testament to the power of the Constitution it could have been. I believe with that one change in American history we would be in such a different place today. Talk of racism would be in the past. Instead, this period, while economically dynamic for some, created immense wealth for a few at the cost of widespread exploitation and suffering for many, sparking the nascent labor movements that would demand reform for decades to come.

Following a brief period of economic instability (the Panic of 1873 and its aftermath), the Gilded Age (roughly 1870s-1900) truly cemented America’s rise as an industrial giant. This era spanned numerous Republican presidencies (Hayes, Garfield, Arthur, Harrison, McKinley) and one Democratic (Grover Cleveland). Republican policies during this time overwhelmingly favored big business, industrial growth, and a strict “laissez-faire” (hands-off) approach to government regulation. The philosophy was that the market would regulate itself, and government interference would only hinder progress. High tariffs were consistently implemented to “protect” booming domestic industries from foreign competition, aligning with a more nationalist economic perspective. The focus was almost entirely on accelerating capital accumulation and maximizing industrial output.

The social climate of the Gilded Age was a paradox: a veneer of opulent wealth often masked by deep poverty and significant social unrest. It was a time of unprecedented rapid urbanization, with millions flocking to cities, many of them new immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe, seeking opportunity. The cultural narrative was dominated by a strong belief in rugged individualism and the “self-made man,” embodied by figures like Andrew Carnegie. However, this often went hand-in-hand with a social Darwinist viewpoint that justified vast wealth disparities as a natural outcome of competition, suggesting the poor were simply less “fit.” There were growing calls for social reforms, fueled by muckraking journalists exposing the grim realities of urban poverty and industrial exploitation. There is an HBO show called the “Gilded Age” that I think perfectly embodies this period.

External factors during this era involved some continued technological exchange with Europe, but America’s own burgeoning industrial capacity increasingly turned its focus inward, as it developed its vast domestic market. The sheer scale of the U.S. meant that internal trade and resource extraction were primary drivers. Internal factors included rapid technological advancements (like the widespread adoption of electricity, the invention of the internal combustion engine, and advances in communications), the development of efficient mass production techniques, and the aggressive formation of massive trusts and monopolies (e.g., in oil, steel, railroads) that profoundly reshaped the economic landscape, concentrating power and wealth in unprecedented ways.

Economic Impact on Society: This era saw truly unprecedented wealth creation, particularly for industrialists like Andrew Carnegie (steel) and John D. Rockefeller (oil), who amassed fortunes that remain staggering even by modern standards. Their opulent lifestyles became legendary. The burgeoning middle class, comprised of professionals, managers, and skilled workers, also saw their living standards improve significantly. However, the inequality was extreme and starkly visible.

Industrial laborers, many of them recent immigrants facing language barriers and discrimination, toiled in dangerous factory conditions for meager wages, leading to frequent and often violent labor strikes (like the Pullman Strike). Urban slums proliferated, and poverty was rampant for a significant portion of the population. African Americans in the South faced increasing Jim Crow laws, violence, and economic disenfranchisement that effectively locked them out of the industrial boom. This period, while economically dynamic for some, came with immense social costs, fueling the progressive movements that would seek to address these imbalances in the early 20th century.

The Golden Era: Prosperity, Social Unity, and Shifting Global Dynamics

This period of America’s economic prosperity demonstrates the complex interplay of policy, external context, and profound societal shifts, often defining what “success” meant for an entire generation.

The Post-World War II Era (roughly 1948-1967) stands as perhaps the quintessential “golden era” for the American economy. It spanned primarily Democratic presidencies (Harry S. Truman, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson) with a Republican interlude (Dwight D. Eisenhower, who largely maintained the New Deal and Great Society’s foundations). Democratic policies during this time focused on robust government investment in public infrastructure, like the sprawling Interstate Highway System, which dramatically improved transportation and commerce. Crucially, legislation like the GI Bill provided unprecedented opportunities for millions of returning veterans to pursue higher education, vocational training, and homeownership with low-interest, government-backed loans. These policies cultivated a highly skilled workforce and fueled a massive domestic consumer market, becoming foundational pillars of the era’s growth.

The social climate was one of relatively strong national unity, forged by the shared experience of the war. There was a prevailing belief in progress and a broadly shared prosperity that fostered the growth of a vast American middle class. The cultural ideal of the nuclear family and the suburban boom (driven in part by the GI Bill) defined a particular lifestyle and consumption pattern, reinforcing certain social norms. However, this idyllic image was deeply flawed by pervasive racial segregation and gender inequality, which systematically limited the full participation of African Americans and women in this prosperity. The nascent Civil Rights Movement was pushing against these entrenched social barriers, setting the stage for future upheavals.

The unparalleled economic success was heavily influenced by crucial external factors. The industrial capacity of Europe and Asia lay in ruins after WWII, meaning the United States emerged as the undisputed global manufacturing powerhouse. We faced virtually no serious competition for decades, allowing American industries to dominate international markets, fuel massive exports, and create widespread employment at home. The Bretton Woods system, established after the war, provided a stable international financial framework with fixed exchange rates, which greatly facilitated global trade and investment. Internally, high personal savings rates accumulated during wartime rationing provided a significant pool of capital for investment. A relatively strong labor movement ensured that wages for many industrial workers rose in tandem with productivity, further bolstering consumer demand and ensuring a more equitable distribution of the era’s gains than in previous booms.

Economic Impact on Society: This era saw a dramatic expansion of the middle class, truly defining the “American Dream” for millions. Widespread gains in living standards were achieved by many white Americans, who benefited from secure jobs, rising real wages, and affordable homes. Homeownership rates soared, transforming the social landscape through suburbanization. However, the benefits were glaringly unevenly distributed along racial lines. African Americans, despite their valiant service in the war, faced systemic discrimination in housing (e.g., through redlining and restrictive covenants), employment, and education (e.g., segregated schools), severely limiting their access to the era’s prosperity and creating a stark racial wealth gap that persists today. Women, while having entered the workforce in large numbers during the war, were often pushed back into traditional domestic roles in the post-war period, limiting their economic independence and professional advancement.

Later, the “Long Boom” (1982-2000) represented another incredibly prolonged period of economic expansion, spanning Republican administrations (Ronald Reagan, George H.W. Bush) and a Democratic one (Bill Clinton). The initial impetus is often traced to Reagan’s Republican policies, particularly his “supply-side economics.” This involved significant tax cuts, especially for corporations and high-income earners, and a strong push for deregulation across various industries. Proponents argued these measures stimulated investment, fostered entrepreneurship, and ultimately led to increased productivity and job creation. The social climate of the Reagan era saw a powerful resurgence of conservatism, a renewed focus on individual responsibility, and a strong anti-communist stance that deeply resonated with many Americans as the Cold War reached its final stages. This period also marked the true beginning of significant technological shifts that would reshape daily life.

Crucially, this period was significantly aided by critical external factors. The eventual stabilization of volatile oil prices after the shocks of the 1970s removed a major inflationary pressure. There was also a broader global shift towards more free-market ideologies, and the weakening of the Soviet Union’s influence ushered in an era of greater globalization, opening new markets and supply chains that benefited the U.S. economy.

When Bill Clinton, a Democrat, took office, he continued to preside over this boom. His administration’s focus on fiscal discipline, including some tax increases on the wealthiest and successful efforts to reduce the national debt (leading to budget surpluses), alongside the passage of trade agreements like NAFTA, further sustained the growth. But perhaps the most undeniable internal factor providing immense tailwinds throughout the 1990s was the burgeoning internet and technological revolution. This independent wave of innovation, creating entirely new industries, dramatically boosting productivity across sectors, and revolutionizing communication, provided fertile ground for economic expansion. The social climate of the Clinton era felt relatively peaceful and prosperous, marked by the end of the Cold War and an increasing embrace of globalization. The rise of new communication technologies began to profoundly reshape social interactions, entertainment, and work patterns.

Economic Impact on Society: The Long Boom saw impressive overall job growth and a significant reduction in unemployment across many segments of society. However, this period also coincided with a widening income inequality. While the nascent tech sector created a new class of millionaires and offered incredible opportunities for those with relevant skills, continued deindustrialization severely impacted traditional manufacturing communities, leading to widespread job losses and economic distress for many working-class families who had previously enjoyed stable, well-paying jobs. The benefits of globalization and technological advancement were not evenly distributed; highly skilled workers, those in finance, and those in the tech sector often benefited disproportionately, while those with less education or in declining industries saw their economic prospects stagnate or worsen. This growing disparity laid the groundwork for future political and social discontent, as many felt left behind by the “new economy.”

Periods of Peril: Economic Struggles, Societal Strain, and Policy Limitations

Just as success is multifaceted, so too are economic downturns, often revealing the limitations of even well-intentioned policies when confronted by severe internal or external shocks. These struggles invariably place disproportionate burdens on different groups, exacerbating existing social tensions.

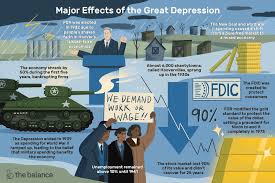

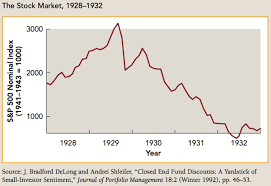

The most catastrophic economic period in U.S. history remains The Great Depression (1929-1939), a decade-long nightmare that began under Republican Herbert Hoover and then continued for much of Democratic Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidency. While the initial trigger was the infamous stock market crash of 1929, Hoover’s Republican administration’s policy choices are widely criticized by economists for significantly exacerbating the crisis.

The Smoot-Hawley Tariff Act of 1930, a protectionist measure designed to shield American industries from foreign competition, stands as a prime example of a policy failure. Intended to protect American jobs, it instead triggered immediate and fierce retaliatory tariffs from other nations, leading to a catastrophic collapse in international trade and deepening the worldwide economic downturn – a clear instance of an internal policy having disastrous external consequences. Internal factors, such as widespread bank failures due to a fragile and unregulated financial system, rampant speculation in the stock market, and a severe deflationary spiral (prices falling, which discouraged spending), further compounded the crisis.

Socially, the Great Depression was a period of unimaginable hardship, widespread despair, and significant social unrest. The social climate was one of profound anxiety, with millions of families struggling daily for basic survival, facing eviction, hunger, and homelessness. There was also a significant rise in radical political movements advocating for fundamental changes to the American system. Economic Impact on Society: Unemployment reached an unprecedented 25%, devastating families across all demographics, particularly men who had traditionally been the sole breadwinners. Farmers faced foreclosures and poverty as crop prices plummeted. African Americans and other minority groups were often the “last hired, first fired,” experiencing even higher unemployment rates and exacerbated racial discrimination. Women, while facing immense societal pressure, often found themselves forced into the workforce, often in low-wage domestic or service jobs, to support their families, reshaping household dynamics. While FDR’s New Deal policies (Democratic) provided crucial relief through social programs (like the Civilian Conservation Corps, Public Works Administration, and the foundational Social Security Act) and financial reforms that stabilized the banking system, the full economic recovery from the Depression is largely attributed to the massive industrial mobilization spurred by World War II – an overwhelming external event. Even the New Deal’s broad reach had limitations, sometimes deliberately excluding certain groups, particularly agricultural and domestic workers, who were disproportionately Black and Hispanic, highlighting how even progressive policies can reflect existing social biases.

The Stagflation Era (roughly 1967-1982) presented a novel and frustrating economic challenge. Spanning both Democratic (Lyndon B. Johnson, Jimmy Carter) and Republican (Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford, and early Ronald Reagan) presidencies, this period was characterized by “stagflation” – a baffling combination of high inflation (rising prices), slow economic growth (stagnation), and high unemployment. Democratic President Lyndon B. Johnson’s increased spending on the Vietnam War and his ambitious “Great Society” social programs, largely unfunded by corresponding tax increases, is often cited as an internal policy decision that contributed to initial inflationary pressures. Socially, this period was marked by profound social upheaval: the intense struggles of the Civil Rights Movement, massive anti-war protests against Vietnam, and rapidly evolving gender roles. This turbulent social climate could sometimes divert political attention and resources from purely economic concerns and created an environment of societal friction and uncertainty that impacted economic confidence. Later, Republican President Richard Nixon’s imposition of wage and price controls in an attempt to curb inflation is now largely seen as a failed policy that distorted markets, led to product shortages, and proved ultimately ineffective in the long run.

The most dominant external factors during this period were the OPEC oil embargoes of 1973 and 1979. These sudden and dramatic increases in global energy prices cascaded through the entire economy, fueling inflation by raising production costs for everything, while simultaneously reducing consumer purchasing power and slowing down industrial output. These were immense shocks that proved incredibly difficult for any administration’s domestic policies to counteract. Additionally, increased global competition, particularly from revitalized and highly efficient European and Japanese industries, began to seriously challenge U.S. manufacturing dominance, leading to job losses in traditional sectors. Economic Impact on Society: Stagflation hit the working and middle classes particularly hard. Rapidly rising prices eroded savings and real wages, making it increasingly difficult for families to afford basic necessities like food, gas, and housing. High unemployment meant pervasive job insecurity, creating widespread anxiety. Those on fixed incomes, like retirees, saw their purchasing power plummet. This period contributed to growing economic anxieties and a sense of decline compared to the post-war boom, fostering a climate of disillusionment and a search for new economic solutions.

The Modern Era: Navigating Crises, Societal Divides, and the Push-Pull of Economic Ideologies

The 21st century has brought its own distinct economic challenges and responses under recent administrations, further illustrating how historical claims play out in contemporary contexts, often within a highly polarized social and political landscape.

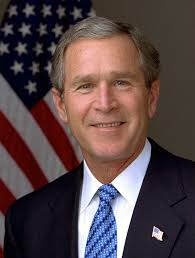

The Great Recession (2007-2009) began with the housing market collapse and subprime mortgage crisis, which escalated into a full-blown financial crisis. This period was largely triggered by factors such as widespread risky lending practices, the securitization of subprime mortgages, and a lack of adequate regulation in the financial sector. The president in office when the Great Recession officially began (December 2007) and when its severity became fully apparent with the collapse of major financial institutions (like Lehman Brothers in September 2008) was George W. Bush, a Republican. While the deepest impact and the subsequent recovery efforts largely fell to his successor, the crisis originated and unfolded significantly during the latter part of President Bush’s second term.

President Barack Obama’s two terms (2009-2017 – Democratic) began amidst the nadir of the Great Recession (2008 Financial Crisis). Obama inherited an economy in freefall, with unemployment rates nearing 10%, a collapsing housing market, and a financial sector on the brink. Socially, the climate was one of intense fear, widespread anger towards financial institutions and perceived corporate greed, and a deep, bipartisan desire for stability and accountability. There was also a growing public awareness of income inequality and the inherent vulnerability of the working and middle classes to systemic shocks. His Democratic policies were characterized by a large-scale fiscal stimulus package (the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009), the controversial but ultimately successful bailout of the auto industry, and significant financial regulation through the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, aimed at preventing future crises. The external factors of the global nature of the 2008 financial crisis meant that the U.S. economy was also heavily impacted by ongoing struggles in Europe and other major trading partners, which weighed heavily on the recovery’s pace. Internal factors like consumer deleveraging (Americans paying down their immense debts) and a cautious banking sector (reluctant to lend after their near collapse) also constrained growth, making the recovery slower than many desired.

Economic Impact on Society: The Great Recession disproportionately impacted lower-income households, minority communities, and those in areas hit hardest by the housing market collapse. Millions lost their homes, their jobs, and their life savings. The recovery, while steady in terms of job growth and unemployment reduction, was often criticized for being “jobless” in its initial stages and for not reaching all segments of society equally. Many Americans felt deeply let down by the financial system and the political response, contributing to a simmering sense of resentment and division that would manifest in later political shifts and populist movements. The slow pace of recovery for some segments of the population exacerbated existing social and economic divides, highlighting persistent inequalities.

Before my fellow Obama fans target me for repeatedly pointing out that his administration’s GDP recovery was slower than many wanted it to be, this is an accurate pronouncement and is the main criticism that many of his opponents use to discount his success in recovering from the catastrophic recession that he inherited. Yes, the GDP growth during Obama’s recovery was, by many metrics, slower than some other post-recession recoveries, particularly compared to the strong bounce-back seen after the 1981-82 recession under Reagan. To his administration’s defense however, I will add these points.

It’s crucial to acknowledge the unprecedented nature and depth of the 2008 financial crisis. Recoveries from financial crises are often inherently slower and more difficult than recoveries from “normal” business cycle recessions. Comparing it directly to recoveries from milder downturns or even the Depression (where the baseline was so much lower) doesn’t always tell the full story. The challenge for Obama was not just restarting growth, but repairing a fundamentally broken financial system, which takes time and can limit the immediate speed of recovery. Considering this, Obama handed over to Trump a recovering economy.

President Donald Trump’s term (2016-2020 – Republican) inherited an economy that was already in a sustained recovery phase from the Great Recession, with declining unemployment and steady, albeit moderate, GDP growth. Socially, this era was marked by unprecedented political polarization, intense cultural clashes, and deep-seated anxieties about globalization, trade, and immigration among segments of the population. Trump’s Republican policies included the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017, which significantly reduced corporate and, to a lesser extent, individual income tax rates, and a strong push for deregulation across various sectors. These policies were intended to stimulate further growth through increased business investment and reduce costs, aligning with classic supply-side principles. For the first three years of his term, the economy did indeed continue its trend of low unemployment and modest GDP growth, extending the recovery that began under Obama. Supporters attributed this directly to his tax cuts and deregulation. Economic Impact on Society: The pre-pandemic growth continued to reduce unemployment across various demographic groups, and wage growth for lower-income workers saw some acceleration. However, the tax cuts were largely perceived as disproportionately benefiting corporations and the wealthy more than the middle or working class, potentially exacerbating wealth inequality. This perception contributed to ongoing social debates about fairness and economic justice.

Trump’s hallmark trade protectionism, involving the imposition of tariffs (taxes) on imported goods from key trading partners like China, Europe, and Canada, represented a significant internal policy shift. While aimed at protecting specific domestic industries (like steel and aluminum) and appealing to a segment of the working class (a key part of his social base that felt left behind by globalization), these tariffs also led to increased costs for American businesses and consumers due to higher import prices. They also created global economic uncertainty, disrupting established supply chains and leading to retaliatory tariffs that harmed American exporters. The ultimate and overwhelming external factor defining his term, however, was the unforeseen and unprecedented global COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020. This devastating health crisis triggered widespread lockdowns, business closures, and a sharp, albeit brief, recession that completely overshadowed and overwhelmed most pre-existing economic policies. The social response to the pandemic, including government-mandated lockdowns, debates over mask mandates, and differing approaches to public health, also heavily impacted economic activity and further deepened social and political divides, directly affecting how the economy could function and recover.

Finally, President Joe Biden’s term (2020-Present – Democratic) began as the economy was emerging from the sharp but brief COVID-19 recession but immediately contending with persistent global supply chain disruptions and rapidly rising inflation. Socially, the climate has been characterized by continued pandemic fatigue, heightened calls for racial and social justice, and enduring, deep partisan divides, particularly regarding the appropriate role of government in the economy and society. His Democratic policies included the large-scale American Rescue Plan (2021), a significant fiscal stimulus package aimed at pandemic relief and broader economic recovery (including direct payments to individuals, expanded unemployment benefits, and aid to state and local governments). This was followed by the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law (2021), a major investment in roads, bridges, public transit, and broadband, and later the Inflation Reduction Act (2022), focused on climate change, healthcare costs, and tax reform, as well as the CHIPS and Science Act (2022), aimed at boosting domestic semiconductor manufacturing. The economy under Biden experienced very strong job growth and a rapid reduction in unemployment. However, this was accompanied by the highest inflation rates in decades.

Economic Impact on Society: The rapid job growth and historically low unemployment benefited many Americans, leading to a strong labor market with increased worker bargaining power. However, inflation disproportionately affected lower and middle-income households, whose wages often did not keep pace with the rapidly rising costs for necessities like food, gas, and housing. This created a widespread sense of economic dissatisfaction and insecurity, even amidst otherwise positive employment numbers. The policies aimed at boosting domestic manufacturing and infrastructure are designed for long-term benefits, aiming to create stable, well-paying jobs for American workers, particularly in blue-collar sectors, addressing some of the long-standing social anxieties about deindustrialization and aiming for a more equitable distribution of opportunity. However, the ongoing challenge of inflation has meant that even with more money, many families feel less secure in their financial standing.

The external factors fueling this inflation have been significant: ongoing global supply chain issues (exacerbated by the pandemic’s lingering effects and geopolitical events), the war in Ukraine (which dramatically pushed up global energy and food prices), and persistent strong global demand for goods and services. Internal factors such as robust consumer demand (fueled by prior stimulus funds and accumulated savings) and a very tight labor market (with more job openings than available workers) also played crucial roles in driving up prices. The Federal Reserve’s response of aggressive interest rate hikes has also been a major independent factor in recent economic developments, aiming to curb inflation but also risking a slowdown and significantly impacting the housing market by making mortgages much more expensive. The social implications of high housing costs and rising interest rates have been particularly felt by younger generations and first-time homebuyers, adding another layer of economic stress.

The Bottom Line: Promises vs. Reality, and Who Benefits

So, when politicians in an election year tell us their specific economic plan is the one-and-only guaranteed path to prosperity, or when they point fingers and solely blame the opposing party for economic woes, history gives us a powerful dose of reality. The truth is far more complex and nuanced. No single president, no single political party, can take all the credit or all the blame for the nation’s economic performance.

We’ve seen periods of incredible growth under both Republican leadership, emphasizing industrial development, tax cuts, and deregulation (as seen in the Gilded Age’s industrial boom, or Reagan’s supply-side policies in the 1980s). And we’ve seen significant prosperity under Democratic leadership, focusing on government investment, robust social safety nets, and consumer demand (as evidenced by the post-WWII middle-class surge, or parts of the 1990s boom). These economic successes often occurred when the chosen policies aligned with or were amplified by incredibly favorable international conditions (like America’s industrial dominance after WWII or the end of the Cold War) or transformative technological revolutions (like the railroads and electricity of the Gilded Age, or the internet in the Long Boom). Crucially, the prevailing social contract and power structures of the time — whether it was the vast wealth disparity and exploited labor of the Gilded Age, the broadly shared but racially segregated middle-class expansion of the post-WWII era, or the increasing income inequalities of the modern era — profoundly dictated who primarily benefited from these booms, and who was left behind.

Conversely, economic downturns have frequently been exacerbated by specific policy missteps, such as protectionist tariffs (a key factor in worsening the Great Depression) or unfunded government spending that fueled inflation (contributing to the Stagflation Era). These struggles were often compounded by immense global financial crises or sudden, unforeseen commodity shocks (like the OPEC oil embargoes or the COVID-19 pandemic). And, almost without exception, these economic downturns disproportionately placed immense burdens on the most vulnerable segments of society, exacerbating existing inequalities and often leading to social unrest and calls for radical change. The Gilded Age’s immense wealth was built on the backs of exploited labor. The Great Depression devastated all but hit minorities and the working poor hardest. Stagflation eroded the buying power of the working and middle classes. The Great Recession disproportionately impacted lower-income families and those who had been excluded from mainstream financial security.

Sustainable economic success is not a magic trick; it’s a dynamic achievement, requiring adaptable and thoughtful policy responses to ever-changing internal dynamics and a turbulent global stage. The bottom line however is success is determined how the people feel.

Conclusion

Biden inherited an economy that was emerging from the sharp but brief COVID-19 recession. His policies resulted in rapid job growth and historically low unemployment which benefited many Americans, leading to a strong labor market with increased worker bargaining power but this success was derailed by inflation, meaning that even with more money, many families felt less secure in their financial standing.

Trump inherited an economy that was already in a sustained recovery phase from the Great Recession, with declining unemployment and steady, albeit moderate, GDP growth. He successfully maintained this growth with tax cuts and deregulation. His economy however was derailed by the Covid pandemic, leading into a recession that disproportionately affected the middle and lower classes. Neither president won their reelection bids.

The social climate and a policy’s real-world impact on different segments of society are not mere byproducts; they are integral components of what truly constitutes “economic success” for a nation. Voters seeking to understand true economic prospects would do well to look beyond partisan slogans and instead evaluate the proposed policies in light of the historical interplay between presidential actions, the powerful, often unpredictable, forces that shape the national and global economy, and the crucial, enduring question of who truly benefits. The next opportunity you get to vote for a president make sure you are looking at more than what you think they can do for your pocket. That part is never guaranteed. History proves it.

Edward Odom