Content:

- I. Introduction: The Collective Struggle and the Three Waves of Attack

- II. Property: The Engine of American Power

- III. The Indispensable Engine: Why Black Main Streets Existed

- IV. The First Wave: Violence and the State-Sanctioned Bulldozer

- V. The Second Wave: Policy-Driven Decline and Strategic Neglect

- VI. The Third Wave: Gentrification as the Final Act of Policy Warfare

- VII. Reclaiming the Republics: A Call for Reparative Policy

I. Introduction: The Collective Struggle and the Three Waves of Attack

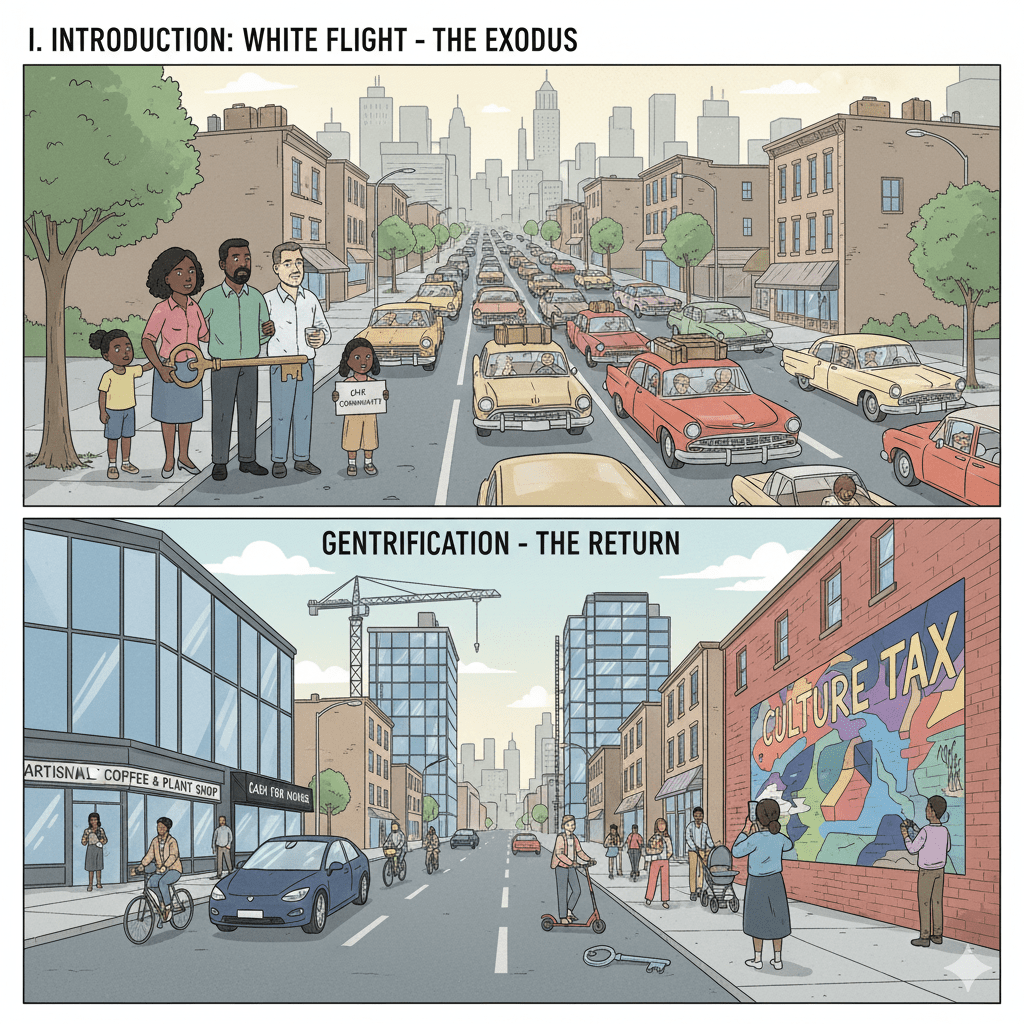

In my circle of Black property and business owners across Brooklyn, NY, a recent topic dominates nearly every conversation: gentrification. We witness daily the phenomenon known as “white flight” reversing itself. White flight was the large-scale migration of people of various European ancestries from racially mixed urban regions to more racially homogenous suburban or exurban areas. This movement, spurred by public policy and racial anxieties, led to a rapid devaluation of inner-city homes. In the vacuum it created, Black families—finally freed from some of the overt housing discrimination of the past—were able to purchase homes, transforming areas like Harlem and Bedford Stuyvesant into vibrant centers of Black culture and commerce.

Today, the tide has turned. The reasons for the reversal of white flight are primarily economic and structural:

- Exhaustion of the Suburban Model: Post-2008 economic shifts and rising suburban costs (long commutes, energy, and property taxes) have made car-dependent living financially burdensome for many.

- Scarcity of Urban Assets: The historic Black neighborhoods often possess the best remaining urban assets—large homes, proximity to job centers, and established public transit—that were made artificially cheap by decades of Redlining and neglect.

- The “Culture Tax” Appeal: Developers leverage the “cool factor” created by decades of Black stewardship, effectively monetizing the culture of the community while simultaneously displacing the people who created it.

Now, those neighborhoods are seeing a dramatic “upscaling” that is widely touted as revitalization. However, this process often does not benefit the original Black occupants and owners because the core goal is displacement. We experience this firsthand: we constantly receive unsolicited calls, notes, and direct mail offering quick cash for our properties—offers we always refuse, guided by the wisdom of our elders who taught us the generational value of ownership in America. Yet, despite our refusal, we see the complexion of the neighborhoods change around us.

This modern displacement, broadly termed gentrification, is the predictable final phase of a century-long, policy-driven war on Black self-determination. The decline of Black business districts is not an unfortunate market accident; it is the inevitable result of a deliberate, shifting political and policy framework. To understand why Black Main Streets are vanishing today, we must trace the continuum of destruction, a war whose enduring violence is rooted in the immense importance of property ownership—the engine of American power. This conflict has systematically dismantled Black self-determination across three phases:

- The First Wave (1898-1960s): Overt Violence and State-Sanctioned Bulldozing.

- The Second Wave (Mid-20th Century): Policy-Driven Decline and Strategic Neglect (e.g., Redlining).

- The Third Wave (Today): Gentrification as the Capitalization of Neglect.

II. Property: The Engine of American Power

The motivation for this enduring conflict lies in the immense importance of property ownership in the American political and economic system.

Owning land or a home is not merely about shelter; it is the primary source of generational wealth. Property is the core mechanism for accessing capital, allowing owners to tap into equity needed to fund a child’s education, start a business, or survive an economic crisis. For Black America, it represents the only path to closing the racial wealth gap, which is precisely why it is systematically attacked. For context, the median white household held roughly eight times more wealth than the median Black household in 2019, a gap overwhelmingly attributable to differences in home equity and ownership rates.

Beyond finance, property ownership grants an essential civic and political dividend. Property taxes fund local infrastructure, and owning property means you are directly investing in and demanding accountability from your local resources. Furthermore, property owners historically form the core of the local tax base, granting them disproportionate political influence in key decisions like zoning and municipal priorities. Control over land equals control over the local political narrative, and it is this trifecta of control—economic, civic, and political—that the systematic dismantling of Black Main Streets aims to seize.

III. The Indispensable Engine: Why Black Main Streets Existed

The Black Main Street—often called a “Black Wall Street”—was a direct, self-determined response to the deliberate exclusion from the American economic and political mainstream. These districts were not created by choice, but by necessity. When Black Americans were denied loans from white banks, barred from purchasing insurance, and prohibited from shopping or seeking medical care in white neighborhoods, they pooled their resources and built their own self-sustaining economies.

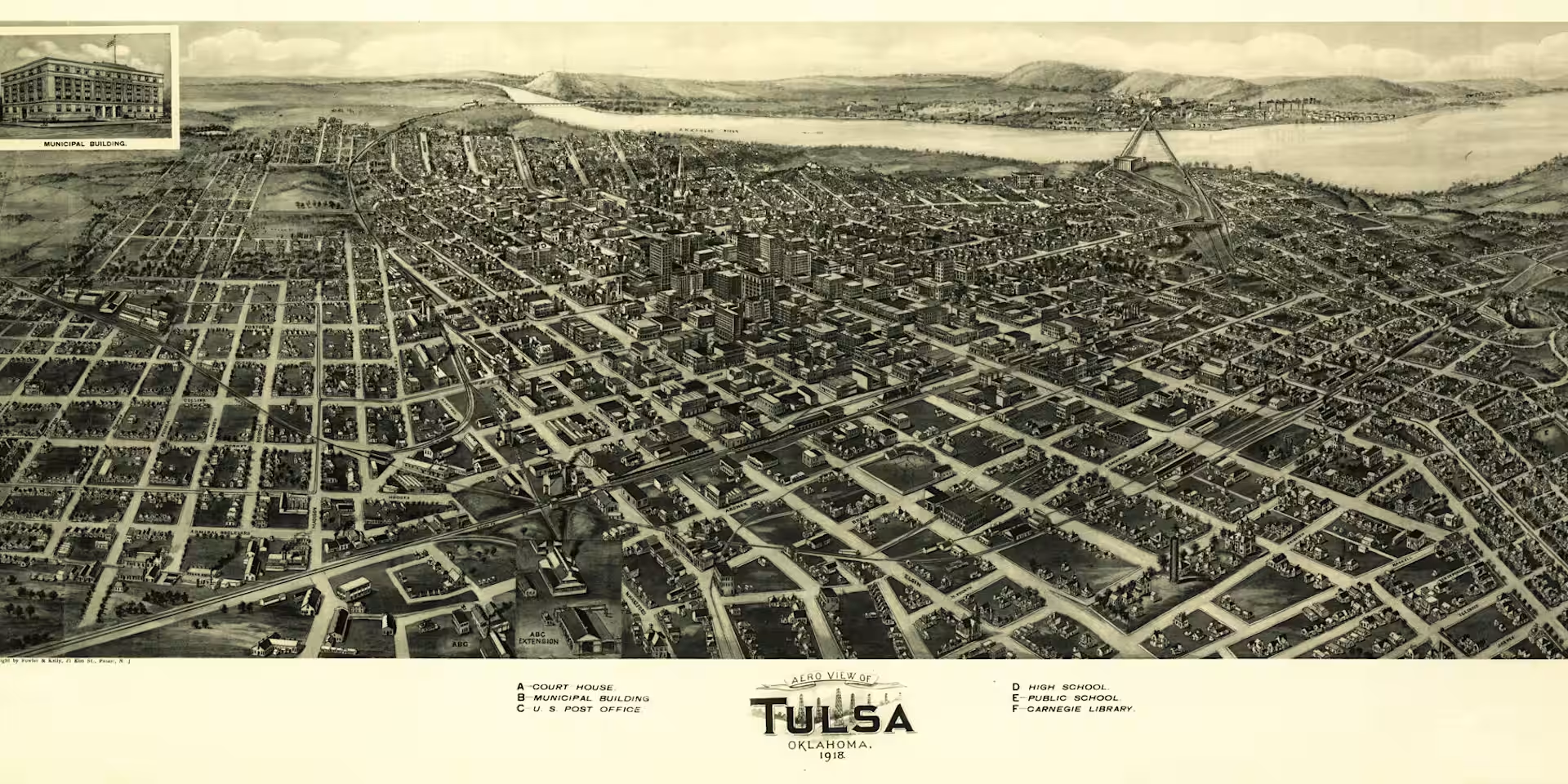

These thriving centers were more than just rows of shops; they were political hubs. In places like Tulsa’s Greenwood, Durham’s Parrish Street, and Richmond’s Jackson Ward, the businesses provided the financial engine and the physical meeting grounds for political organizing. They funded Civil Rights organizations, served as sites for voter registration, and incubated the independent Black leadership required to challenge the established political order. They represented economic and political sovereignty—a state of autonomy that was intolerable to the dominant power structure.

IV. The First Wave: Violence and the State-Sanctioned Bulldozer

The initial attack on Black Main Streets was direct and brutal, proving that the destruction was never an accident, but a calculated political strategy to eliminate competition and seize control. The answer to the question, “Why go to such lengths?” is simple: to permanently secure political and economic advantage.

A. Elimination of Financial Competition (The Overt Motive)

The most overt tactic of the first wave was mass racial violence aimed at destroying Black economic centers, clearing the land for seizure, and terrorizing the population into flight. The motive was land and wealth.

- Case Study: Tulsa Race Massacre (1921), Oklahoma. Over 35 square blocks of the thriving Greenwood district were deliberately burned. In the chaos, white residents and businesses seized the land and properties. The Black families who were robbed of their homes and generational wealth received no compensation.

- Case Study: Wilmington Insurrection (1898), North Carolina. This was a coup d’état. White supremacists overthrew the legitimately elected biracial city government, destroyed the Black-owned Daily Record newspaper, and forced hundreds of prosperous Black citizens to flee. The property and businesses they left behind were seized.

- Case Study: Rosewood Massacre (1923), Florida. The entire, prosperous Black town was systematically destroyed by a white mob. The land was then claimed by the surrounding white community and remained seized for over 70 years, representing a total, uncompensated loss of generational wealth.

B. Destruction by Federal Mandate (Policy as a Weapon)

Following the era of outright mob violence, the tactic evolved into the state-sanctioned destruction of the Federal Highway Act of 1956 and associated Urban Renewal policies. Under the guise of eliminating “slums,” federal funds were systematically used to target and bulldoze thriving Black communities.

- High-Speed Dissection: Destruction for Transportation InfrastructureMassive federal highways were routed directly through cohesive Black communities, scattering the population and destroying the economic corridors:

- Detroit’s Black Bottom and Paradise Valley: The construction of the I-75 and I-375 freeways systematically razed these historic, vibrant Black communities.

- Rondo in St. Paul, Minnesota: The construction of I-94 effectively bifurcated and destroyed the economic and cultural heart of St. Paul’s Black community.

- Eminent Domain Seizure: Destruction for Institutional ExpansionCities used Urban Renewal and eminent domain laws to seize Black-owned land and transfer it to powerful, non-taxable institutions like hospitals, universities, and municipal projects. This was outright property theft disguised as modernization:

- Philadelphia’s University City: The University of Pennsylvania and Drexel University used Urban Renewal funds to clear Black and poor neighborhoods surrounding their campuses for institutional expansion and subsidized faculty housing, forcibly removing residents and seizing valuable urban land.

- Pittsburgh’s Lower Hill District: This cultural mecca was virtually wiped out to build the Civic Arena (a sports stadium) and associated parking lots, removing thousands of residents and hundreds of businesses and collapsing the region’s Black tax base and political power.

This distinction proves that the destruction was sanctioned and funded by federal and local policy, demonstrating the government actively demolished and seized Black-owned property and communal capital for the benefit of politically influential white institutions and infrastructure projects.

V. The Second Wave: Policy-Driven Decline and Strategic Neglect

The next phase involved strategic policy-driven neglect, which achieved the same end—declining property values and vulnerability—without the negative publicity of a bulldozer.

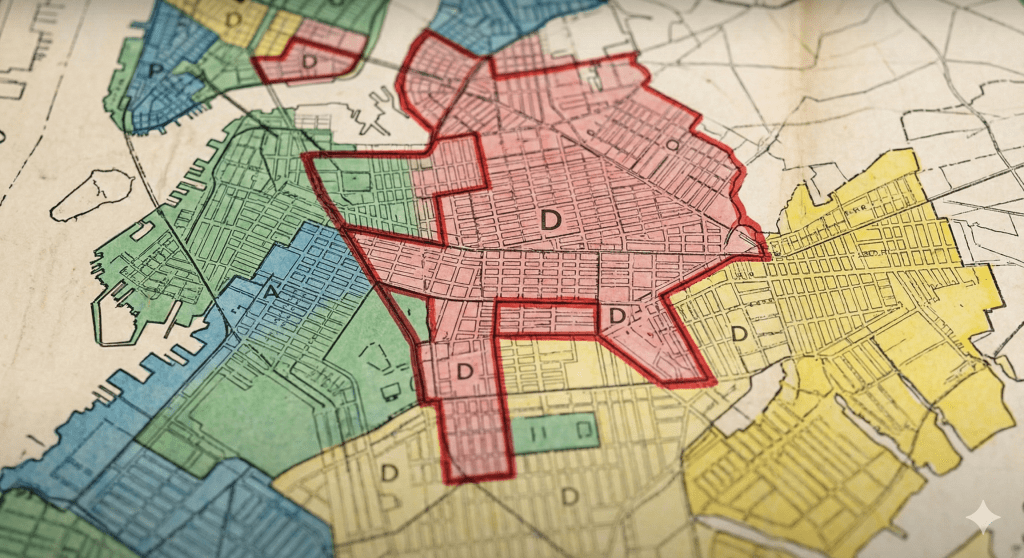

A. Redlining and the Systemic Denial of Capital

For decades, the single most damaging policy was Redlining, enforced by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC).

- Policy Detail: HOLC maps categorized Black neighborhoods as “Hazardous” (or redlined), effectively denying them access to FHA mortgage insurance and private bank capital.

- The Motive: The system was designed to reward economic segregation. Lenders were penalized for investing in integrated or Black neighborhoods and rewarded for investing in segregated white ones.

- The Concrete End: This strategic denial of capital prevented Black businesses from expanding, homeowners from renovating, and communities from attracting investment. This created artificially low property values, making the land “cheap” for later purchase. The consistent denial of capital created a massive, persistent gap in home equity appreciation, leaving those properties uniquely vulnerable.

B. The Political and Social End: Maintaining Political Stability

The goal of this strategic neglect was to ensure a predictable and stable political and economic environment for the dominant power structure.

- Dilution of Political Power: When populations were displaced and scattered by highways or foreclosure, their concentrated local political leverage and voting power were diluted across numerous precincts. This made it harder for them to organize, elect local representatives, and resist disruptive policies.

- Predictable Labor Supply: By limiting access to independent Black capital and stifling entrepreneurship, policies like Redlining ensured a large pool of labor dependent on low-wage employment in the white economy. The destruction of Black self-sufficiency ensures a stable, economically vulnerable workforce, benefiting established industries.

VI. The Third Wave: Gentrification as the Final Act of Policy Warfare

Gentrification today is not a new market phenomenon; it is the capitalization of the previous policy neglect. It is the final, profitable act in the war that began with mob violence and was institutionalized by policy.

The Policy-Profit Connection: Land that was made artificially cheap by decades of Redlining is now bought low by developers and then sold high after the city invests public money (e.g., transit lines, tax breaks). The motive remains the same: a massive wealth transfer from the long-term, dispossessed Black owner to the developer and the new tax base.

The vulnerability is particularly sharp among elderly Black homeowners, who hold substantial equity but may lack familiarity with modern bureaucratic tactics. In addition to predatory cash offers, various tactics are used to entice, force, or trick Black owners out of their hard-earned equity, including:

- Forcing Digital Compliance: Elder owners are increasingly forced to revert to paying property taxes online, leading to missed deadlines and the accrual of fees.

- Targeted Property Tax Scams: Aggressive mailers disguised as official tax or lien documents trick elderly owners into paying fraudulent entities.

- “Deed Theft” and Fraudulent Transfers: Scammers forge signatures or trick owners into signing confusing legal documents that transfer the property’s title.

- Bogus Municipal Violations: Increased, aggressive code enforcement targets properties to create debt, weakening the owner’s financial stability and making them desperate to sell.

The final legal weapon is the Supreme Court ruling in Kelo v. City of New London (2005). This decision authorized cities to seize private property and transfer it to private developers for the purpose of “economic development.” This allows municipalities to label stable, minority-owned business districts as “underperforming” or “blighted” and seize them to benefit wealthy private interests.

Zoning and Upzoning: Cities use seemingly neutral land-use policies to price out current owners. By changing the zoning (Upzoning) to allow for high-rise residential and commercial buildings, the underlying land value immediately skyrockets, forcing existing, low-density businesses and homeowners to sell because the potential tax burden and market pressure become unsustainable. This final phase completes the cycle: the land is cleared, the wealth is transferred, and the original political voice is silenced.

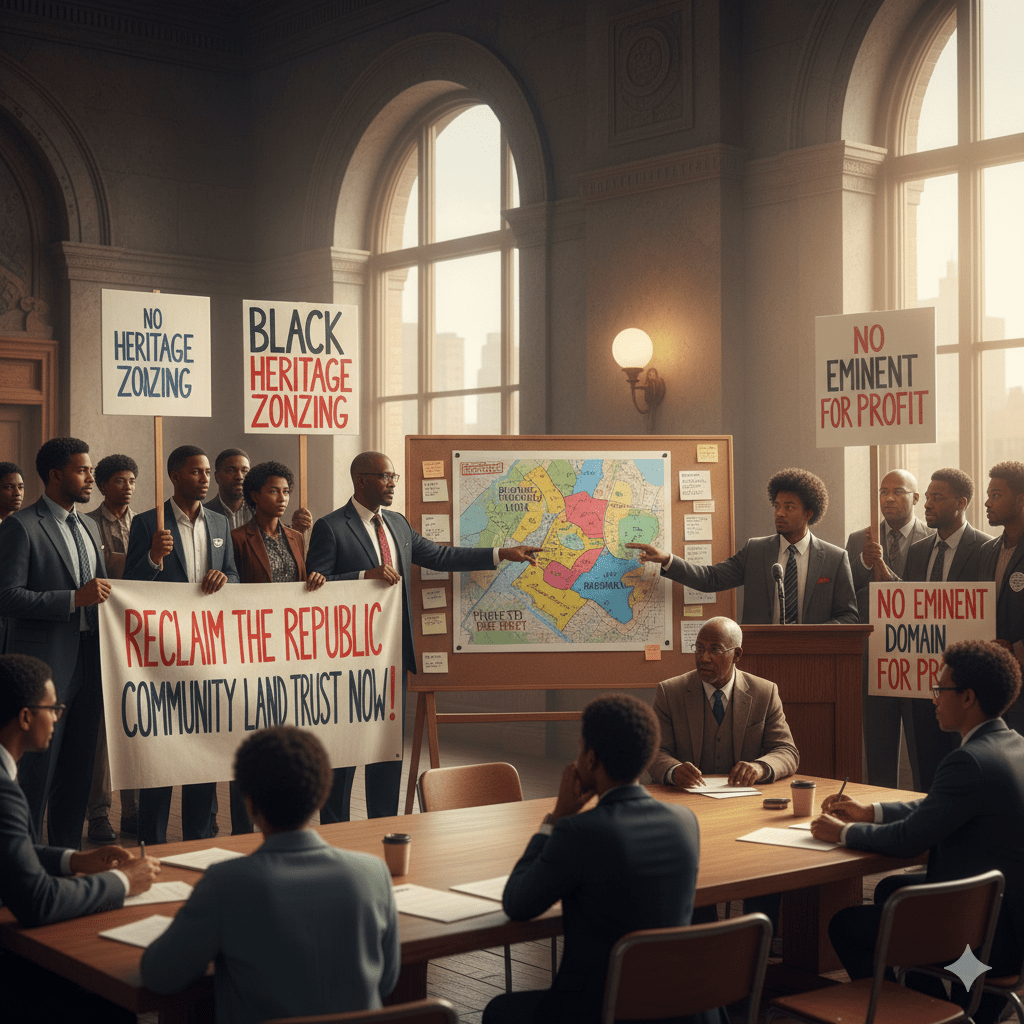

VII. Reclaiming the Republics: A Call for Reparative Policy

The vanishing of the Black Main Street proves that America’s most significant issues—from the racial wealth gap to political instability—are inseparable from land ownership and policy. The motive for the continued use of these tactics is clear: the reliable flow of economic growth and political stability for the dominant power structure.

To reverse this century-long process, we must move beyond critique and implement policies that create political mechanisms for restoration and protection.

- Black Heritage Zoning: Local governments must create specific zoning overlays that protect both the physical structures and the economic function of legacy Black business corridors. This includes prioritizing non-speculative, culturally relevant businesses over national chains.

- Community Land Trusts (CLTs): Cities should actively fund CLTs to acquire land and remove it from the speculative market permanently. CLTs ensure that the land’s value is preserved for community benefit and, crucially, re-concentrate the Black tax base and property-owning political voice that the policy wars were designed to scatter.

- Eminent Domain Reform: We must advocate for statutory changes that abolish the use of eminent domain for private economic development, thereby protecting stable property owners from the final, fatal act of policy warfare.

The war on the Black Main Street is a war on Black self-determination. By recognizing the policy and political motives behind every phase of destruction, we can finally build a framework for economic justice that ensures that what our parents and grandparents built, remains.