Contents:

- Introduction: The Decline and the Discontent

- 1. The Promise of Mobility and the Persistence of Class

- 2. The Racial Wedge: Preventing the Working-Class Coalition

- 3. From Industrial Security to Tech Age Anxiety

- 4. Political Exploitation and Misdirection

- Conclusion: The Choice Between Division and Power

My work, grounded in African American history, usually examines the struggle of Black citizens within the United States. Yet, consistent online debate with white conservative critics has highlighted a core truth: their frustration is legitimate. I admit that, as an African American, recognizing the validity of their economic plight is a challenging perspective to adopt. While I reject the misdirected anger toward African Americans and immigrants, I agree with the validity of their economic complaints. This piece shifts focus to analyze the specific experience of the white working class and the structural conditions that have fueled their discontent.

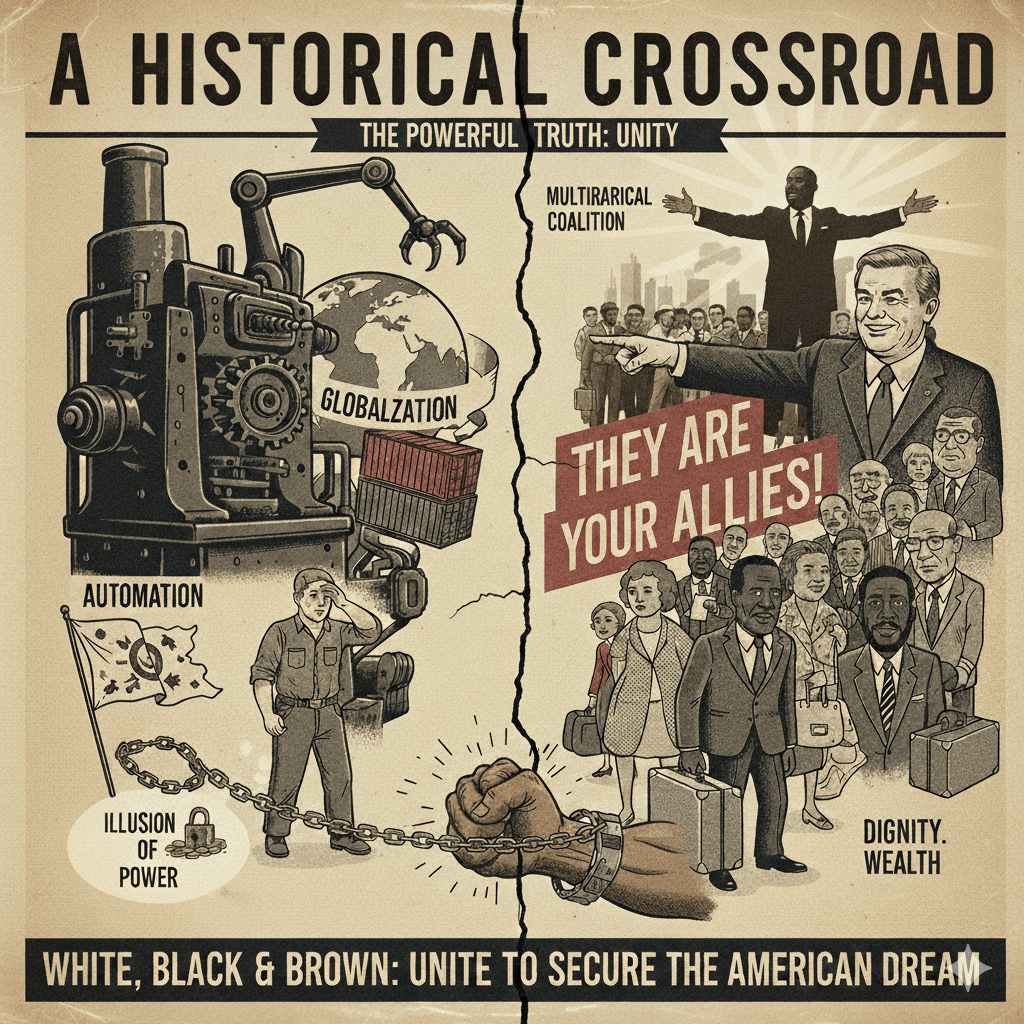

The contemporary anger and political mobilization of the white working class is a complex phenomenon rooted in deep historical and economic shifts. This paper argues that this group has historically been disadvantaged, with the nation’s primary resources reserved for the upper class, and that their relative social standing was strategically maintained through the deployment of racial division to prevent a powerful, multiracial working-class coalition.

Introduction: The Decline and the Discontent

The contemporary political landscape is defined, in part, by the visible anger and mobilization of white working-class America. This sentiment is not merely a reaction to recent events but is rooted in a historical structure that has consistently relegated the group to an economically vulnerable, though socially elevated, position. While this population was historically granted a nominal stake in the “American Dream,” their current economic decline provides a factual basis for their feeling of neglect and betrayal.

This decline is measurable: the real median wage for non-college-educated men has stagnated or declined since the 1970s, a period coinciding with the collapse of labor power. Private-sector union membership has plummeted from its peak of approximately 35% in the mid-1950s to just 5.9% today. These economic wounds, coupled with high rates of “deaths of despair“—defined as mortality from suicide, drug overdose, and alcohol-related liver disease—among this demographic, underscore a profound loss of well-being and status anxiety. The combined death rate from these causes more than doubled between 1999 and 2017 among middle-aged, non-Hispanic white Americans with a high school education or less (Case & Deaton, 2017). This paper asserts that America’s founding elites strategically used racial division (the “racial wedge”) to prevent a unified working-class coalition, a barrier that is now crumbling in the face of structural economic change, leaving this group feeling socially and economically abandoned and ripe for political exploitation.

1. The Promise of Mobility and the Persistence of Class

The formation of the United States promised an escape from rigid inherited class boundaries, offering legal freedom and upward mobility. This promise appealed strongly to European migrants.

However, the political and economic realities were quickly shaped by the colonial elite—merchants, planters, and financiers—who established a societal framework that mimicked the feudal structure they supposedly rejected. The wealthy became the new “lords of capital,” controlling land and finance. The crucial difference was that the American class structure relied on societal and racial barriers, rather than legal hereditary titles, to maintain stratification.

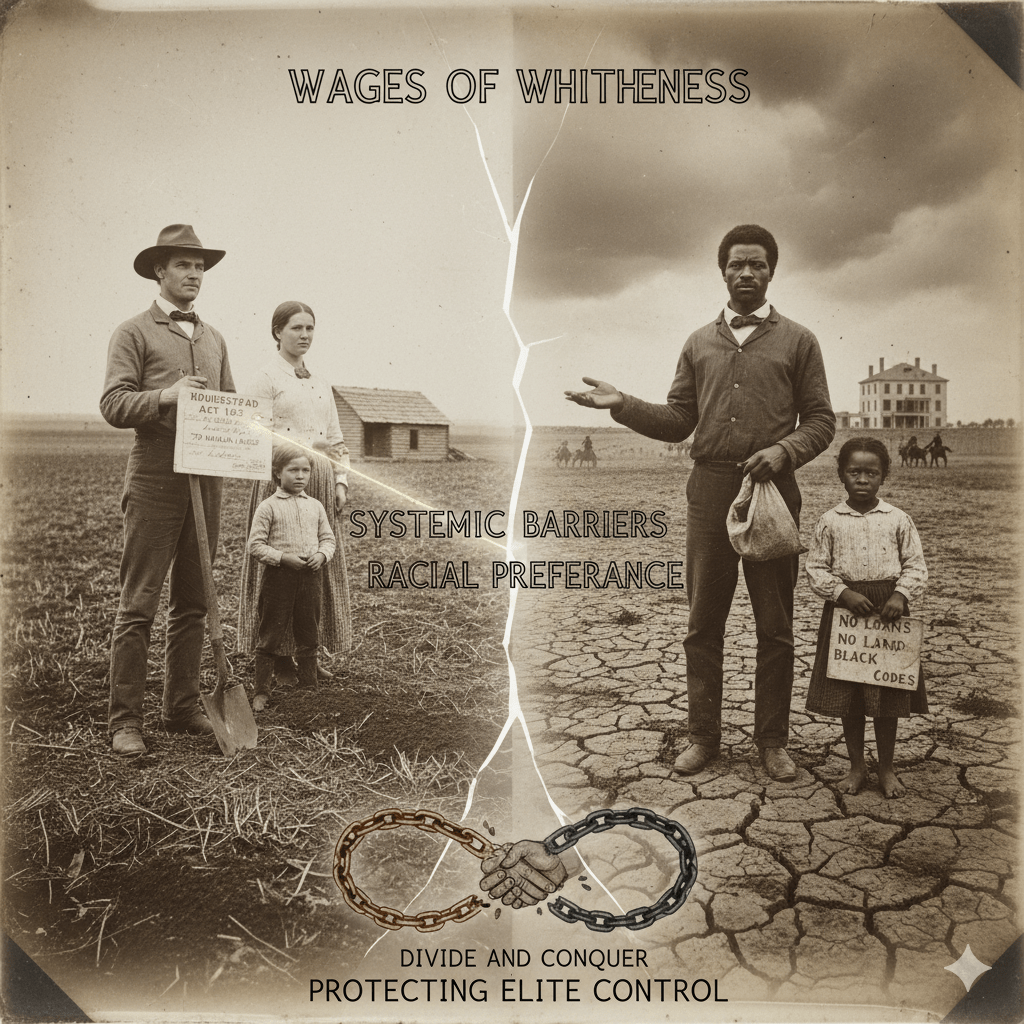

Furthermore, state resources were often allocated with racial preference. Policies like the Homestead Act of 1862, which was a massive transfer of public wealth into private hands, created immense intergenerational wealth for one segment of the population while actively excluding others. This system ensured that even within the working class, access to the nation’s primary resources was racially segmented.

Proof of the “Wages of Whiteness” through State Policy

The Homestead Act of 1862 demonstrates this mechanism of division. This act transferred an estimated 270 million acres of public land, roughly 10% of the U.S. landmass, primarily to white families. It served as a massive early wealth-building mechanism for the white working class, granting them a direct, tangible economic benefit of free land and the subsequent creation of intergenerational wealth, which was systematically denied to Black families and other minorities. By giving one segment of the working class (white settlers) valuable economic assets while simultaneously denying or revoking similar access to others (especially formerly enslaved Black Americans), the government solidified the “wages of whiteness.” This provided white laborers with a superior material and social status, effectively bribing them with state resources to accept their subordinate class position relative to the elites and to reject any coalition with non-white workers.

Reinforcing Class Stratification

This policy ensured that, even if both a Black farmer and a white farmer were technically part of the working or poor class, the white farmer had a state-backed route to independent land ownership and stability, while the Black farmer faced legal (e.g., discriminatory lending, segregation) and extralegal (e.g., violence, terror) barriers. This racially segmented access to wealth made the white working class feel their primary loyalty should be to the system that granted them the land, rather than to the class of excluded workers who could have otherwise been their allies. This segmentation prevented the powerful, unified, multiracial working-class coalition that in my opinion, the elites feared, thereby protecting the overall control of the industrial and financial elite over the nation’s primary capital resources.

2. The Racial Wedge: Preventing the Working-Class Coalition

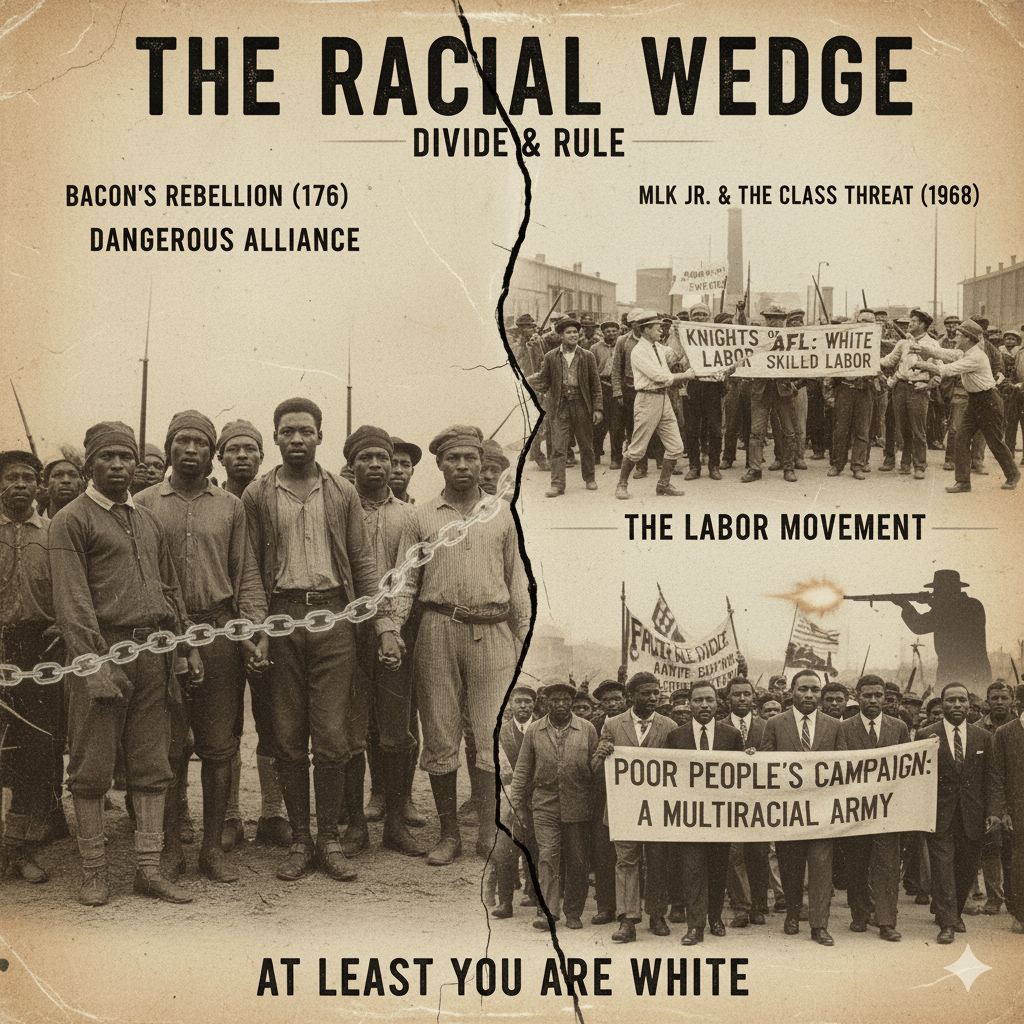

To maintain this class structure, artificial barriers were essential to prevent the working class—the most numerous and powerful potential coalition—from uniting against the elite.

The Original Prevention: Bacon’s Rebellion

The earliest and most definitive threat was realized during Bacon’s Rebellion (1676) in Virginia. The uprising saw a dangerous alliance of poor white indentured servants, enslaved, and free Africans fighting against the wealthy planter elite. Historian Edmund S. Morgan noted that the assembly of the two unfree populations exposed the ruling class’s vulnerability (Morgan, 1975). In response, the elite codified strict race-based slavery laws while simultaneously granting poor whites greater legal status and rights. This action was designed to shatter the potential cross-racial alliance by conferring the “wages of whiteness”—a non-economic, superior social standing—to the white working class (Roediger, 1991). The elite’s message was: “at least you are white,” successfully fragmenting the working class for centuries.

The Labor Movement Prevention: Post-Civil War

During the industrialization of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, robust, multiracial labor unions repeatedly presented a threat. While organizations like the Knights of Labor showed early promise of inclusion, they were often undermined by the rise of more exclusionary unions, such as the American Federation of Labor (AFL). The AFL often prioritized the interests of white male skilled laborers, excluding Black, Asian, and non-skilled workers.

This created a short-term benefit for the white working class—they had better access to higher wages, job security, and housing—but it was ultimately a structural trap. By actively participating in and benefiting from this racial exclusion, they secured minor, temporary advantages that came at the cost of permanent structural power. This fracturing of the labor movement along racial and skill lines prevented a unified mass movement capable of challenging capital on a national scale, to the lasting benefit of the industrial elite.

The Final Prevention: Martin Luther King Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign

The most critical modern instance of preventing a working-class coalition centers on Martin Luther King Jr.’s shift toward economic justice. While King was permitted to operate focusing on legal racial segregation, his movement became a mortal threat when he expanded to dismantle the class barrier. His last major initiative was the Poor People’s Campaign, aimed at forging a “multiracial army of the poor”—including white, Black, Hispanic, and Native American people—to demand fundamental economic rights (Jackson, 2006). This decisive move toward a unified class movement was swiftly and permanently curtailed by his assassination in April 1968, preventing the consolidation of a coalition that could have fundamentally challenged the distribution of wealth and power in America.

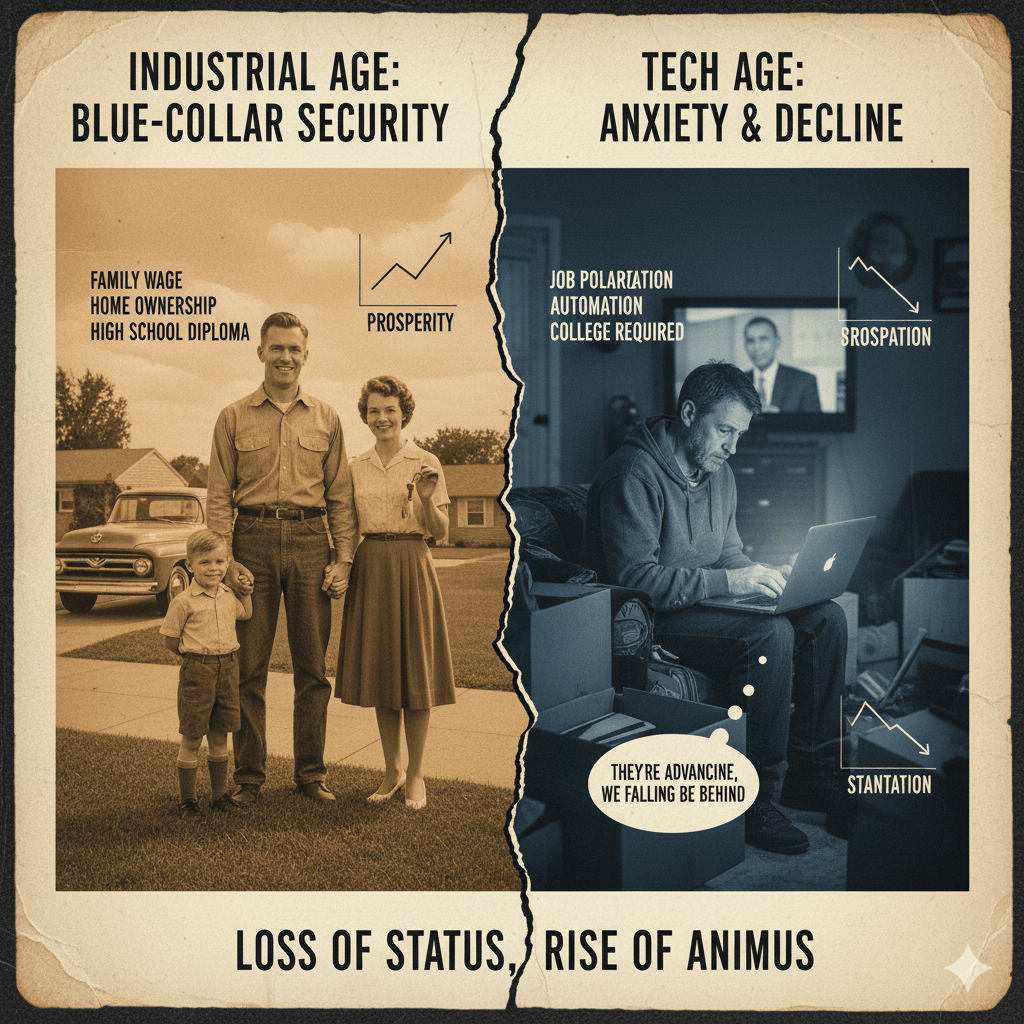

3. From Industrial Security to Tech Age Anxiety

The “wages of whiteness,” combined with the robust demand for blue-collar labor during the Industrial Age, provided the white working class with relative stability. They achieved the American standard of a family wage and homeownership with only a trade or high school education. Because this path provided a decent living, in my opinion, higher education was often not a financial or social priority.

The shift to a knowledge-based, Tech Age economy systematically dismantled this security through job polarization and automation. The value of middle-wage, blue-collar labor declined, while the value of college-educated skills soared. The dramatic increase in the share of national income held by the top 1% since the 1970s is the corollary to the white working class’s economic stagnation.

Simultaneously, the Civil Rights movement provided African Americans with expanded access to higher education and corporate America. This combination created a sense of relative deprivation where white working-class individuals perceived their group as declining relative to their past prosperity and relative to other minority groups who appeared to be advancing just as their own prospects contracted.

The election of Barack Obama (2008), a highly educated African American, served as a profound symbolic blow, shattering the long-held psychological assurance of white racial superiority that had underpinned their class identity. This loss of the guaranteed non-economic capital of whiteness contributed to heightened animus, fueled by the perception that the government was actively catering to minorities while neglecting the increasingly vulnerable white working class (Vance, 2016).

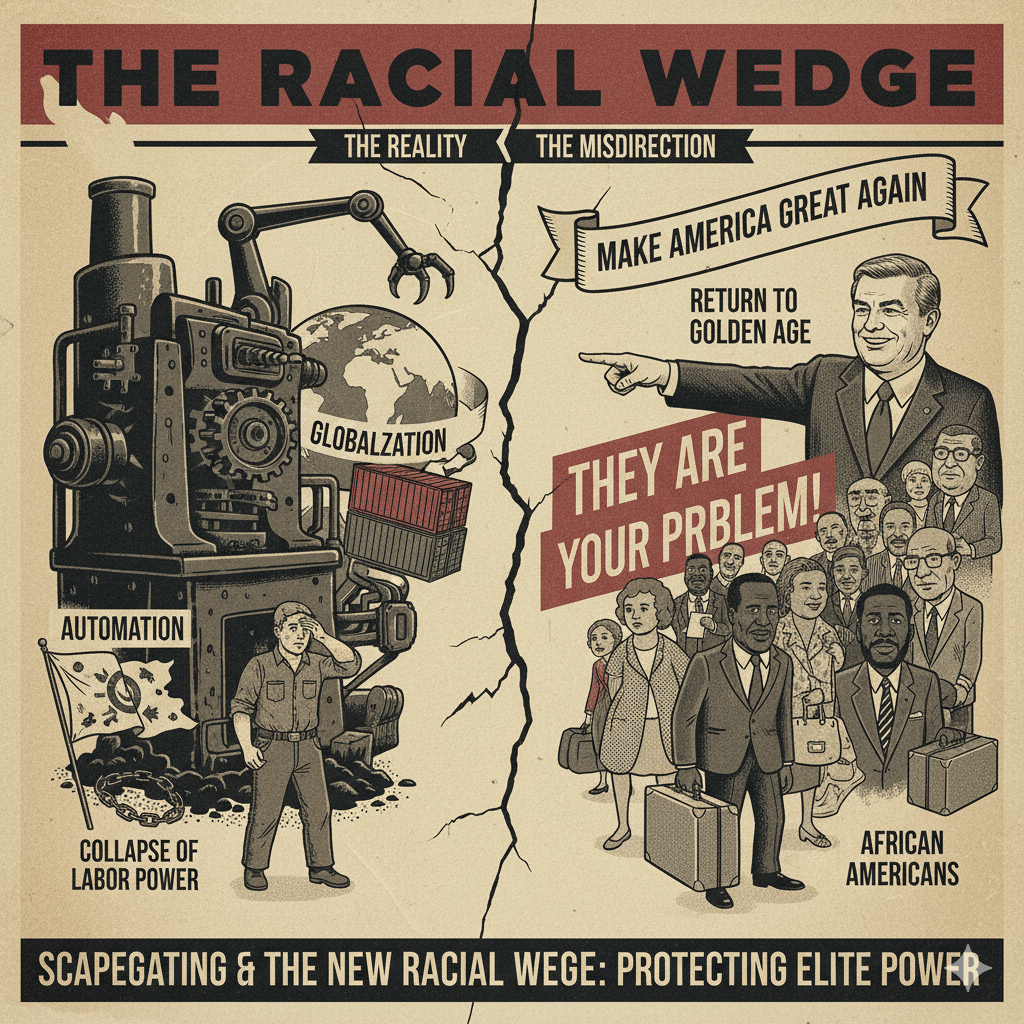

4. Political Exploitation and Misdirection

The resulting anger and sense of abandonment is now being fully leveraged by political administrations who recognize the power of mobilizing a neglected group. They capitalize on the historic insecurity by promising a return to a perceived golden age of industrial employment and social hierarchy.

This political strategy successfully misguides the white working class. Instead of confronting the complex structural causes of their decline—primarily automation, trade/globalization, and the collapse of labor power—the anger is redirected toward traditional scapegoats: immigrants and African Americans.

This maneuver is the modern iteration of the historical racial wedge, avoiding the real issue that their economic value is dissolving in the face of structural change. The political elite successfully mobilizes this group by attempting to revive the feeling of racial superiority—a superiority that was never real economic power, but merely an artificial tool used by elites to ensure their own continued control of capital and power.

5. Real Remedies and the Path to Class Unity

The deep-seated material distress of the white working class demands structural economic remedies, not false symbolic promises. The path forward requires policies that rebuild genuine economic power and restore a stable social footing, ultimately uniting the working class across racial lines by focusing on common economic interests.

Economic and Industrial Remedies

The collapse in collective bargaining power is the primary cause of wage stagnation for this demographic.

- Revitalization of Worker Power and Collective Bargaining: The current low union density (just 5.9% in the private sector) must be reversed. This requires Labor Law Reform that strengthens protections for workers trying to organize, penalizes companies that engage in illegal union-busting, and enables sectoral bargaining (negotiations across an entire industry, not just a single company) to lift wages universally. A federal living wage, indexed to inflation or local cost of living, must be set to provide an essential wage floor.

- Targeted Industrial and Infrastructure Investment: While the old industrial economy is not returning, the government can stimulate a new one. This involves using massive investment in modern infrastructure projects (transportation, energy, water systems) and high-tech domestic supply chains (e.g., semiconductors, clean energy components). These investments must be tied to mandates for prevailing wages (union-level pay) and robust apprenticeship programs to funnel non-college-educated workers into stable, skilled trades.

- Wealth and Income Redistribution: The dramatic increase in the wealth held by the top 1% must be addressed. This requires implementing more aggressive progressive tax schedules on the highest earners and capital gains to fund necessary social investments, and stricter regulations on financial practices to encourage capital investment in productive industrial assets rather than speculative financialization.

Education, Opportunity, and Community Remedies

Addressing the “deaths of despair” requires restoring purpose and providing accessible, debt-free economic opportunity.

- Investment in Non-College Career Paths: Not all stability requires a four-year degree. The government must heavily subsidize or make tuition-free community and technical college programs that align directly with local demand for specialized skilled labor (e.g., advanced manufacturing, robotics repair). Furthermore, expanding and subsidizing high-quality, paid national and local apprenticeship programs that offer workers a wage while they train for a highly skilled career is critical.

- Community and Mental Health Support: Directly combat the social decay underpinning the “deaths of despair.” This includes ensuring access to affordable, comprehensive physical and mental healthcare, including extensive and accessible addiction treatment programs in rural and struggling working-class communities. Public investment must also be directed toward rebuilding and funding local social institutions (community centers, libraries) to restore a sense of communal purpose and stability.

Conclusion: The Choice Between Division and Power

The historical record confirms that the discontent of white working-class America is a legitimate response to decades of economic vulnerability, deliberately maintained by elites who deployed the “racial wedge” to prevent true working-class power. The promise of racial superiority—the “wages of whiteness”—was always an illusion of status, offered as a distraction from the reality of class exploitation. The remedies outlined, from strengthening labor unions to investing in skilled trades and community support, are not racially preferential; they are structural fixes that benefit all non-elite Americans facing automation and globalization. The white working class now stands at a historical crossroads: they can continue to be mobilized by political forces that scapegoat minorities and promise a nostalgic, unattainable past, or they can finally recognize that their economic adversaries are the financial and political elites, not their working-class neighbors. Only by dismantling the historical racial barriers and forging the multiracial coalition that figures like Martin Luther King Jr. died attempting to build can the working class—white, Black, and brown—achieve the collective power necessary to secure the dignity, stability, and wealth that the American system has long promised but only reserved for the few.